“We’re uncool”: Almost Famous and High Fidelity celebrate music—but they’re warnings, too

Image: Graphic: Natalie PeeplesScreenshot: High FidelityScreenshot: Almost Famous

Spinning vinyl looks great on camera: The concentric spirals, the way the light glints off the surface. It’s mesmerizing, and metaphorical, too: You can’t photograph sound in motion, but footage of a needle hitting the outer groove of a record will do just fine.

At the turn of the 21st century, vinyl records were enough of a novelty that putting one onscreen still worked as a shorthand. But in the real world, where the CD was king and MP3s were knocking at the throne-room door, any format with an RPM attached was strictly a specialty concern: DJs scratched them, collectors hunted for them, retro-minded hipsters hung them on their walls. In the 1999 video for Lauryn Hill’s “Everything Is Everything”—the third and final single from an album that sold CDs by the truckload—director Sanji Senaka imagines New York City as a record on an island-sized turntable, its people and buildings rotating around the Empire State Building as a massive stylus scrapes across the streets. The city and the format that built hip-hop, all in one visual package.

The “Everything Is Everything” video went on to pick up a Grammy nod and three MTV Video Music Award nominations in 2000, but it wasn’t the only affirmation of vinyl’s cinematic qualities that year—two big screen releases also had audiophiles celebrating the format. The first was High Fidelity—an adaptation of Nick Hornby’s novel about an unlucky-in-love record-store owner—which opens on a flat, black, and circular image: The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (or maybe it’s a pressing of Nuggets?) cauterizing the wound where Rob Gordon’s (John Cusack) heart used to be. Six months later, at the Toronto premiere of Almost Famous, festivalgoers saw Rolling Stone wunderkind-turned-Academy Award nominee Cameron Crowe recreate his first impressions of The Who’s Tommy, the tiny indentations containing “Amazing Journey” rushing by in an overhead shot. The record’s prismatic Decca label doubles, then triples while the multiple exposures keep the enraptured face of Crowe analogue William Miller (Michael Angarano here, but Patrick Fugit after the dissolve and the segue into “Sparks”) in frame.

To the credit of everyone involved, it’s a miracle that neither of these scenes is unbearably corny. Translating the power of a good pop song to the screen is a tricky business, one that’s flummoxed greater filmmakers than Crowe or High Fidelity director Stephen Frears. (Martin Scorsese works a needle drop like few others, but all those instincts failed to keep the Vinyl pilot from feeling like anything more than a coked-up run through the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame.) It helps to get the words right, and both films have a leg-up in that department: There would be no Almost Famous if Crowe hadn’t been a preternaturally gifted rock scribe drawing on memories of profiling The Allman Brothers Band, the Eagles, and Poco; Hornby, while fairly conservative in his tastes and as navel-gazing as any of his literary creations, writes music criticism in the same conversational tones that makes each of his books double as a prefab screenplay.

It could be diminishing of each film’s individual strengths to link them so closely together like this. They’re unique works with vastly different tones and thematic concerns that don’t all fit cleanly into the confines of two verses, a chorus, and a bridge. Almost Famous is a quasi-memoir and an act of wish fulfillment, a vicarious backstage pass to classic rock’s arena-filling heyday. It’s the best possible use of Crowe’s sentimental streak, with John Toll’s cinematography casting William’s road trip with up-and-comers Stillwater in endless romantic shades. From the parting assurance from his older sister Anita (Zooey Deschanel) that “one day, you’ll be cool” to Penny Lane (Kate Hudson) processing the news that she’s been betrayed by the guitar player she loves, we see so much of Almost Famous through William’s wide eyes that even the parts that would be exhausting to experience in person retain a heady allure. Tailing a tripping Russell Hammond (Billy Crudup) through a suburban party? Big pain in the ass, but hey: It results in a heartwarming Elton John singalong, and is an excellent anecdote for the magazine feature you’re being paid a grand (in 1973 dollars) to report.

High Fidelity doesn’t come anywhere near that level of access: The Chicagoans at Rob’s store, Championship Vinyl, are “professional appreciator”s from afar who can barely hold it together in conversation with rising singer-songwriter Marie De Salle (Lisa Bonet). It’s a much more grown-up male adolescent fantasy (i.e. Rob winds up having a one-night stand with Marie) where the specters of age, responsibility, and purpose are always hovering around while only occasionally impeding on Rob’s daytime routine of listening to music and rattling off personal top five lists, or his off-hours regimen of listening to music and rattling off personal top five lists. High Fidelity is a film colored by a love of music, but it’s also about love love, the complexities of romantic relationships and the path toward becoming a better, fuller person.

We watch Rob drink a lot, smoke too much, and put his records in “autobiographical” order, but we’re never really in his shoes. Though we’re invited into his head to see how he remembers his history of romantic fuck-ups, the choice to air so many of his inner thoughts in direct address is one of distance. When Cusack monologues, Frears isn’t so much breaking the fourth wall as he is relocating the Championship counter to the Kinzie Street Bridge or the bar at the Green Mill. He may as well throw in a sales pitch for The Three EPs by The Beta Band, because Rob’s talking at his audience, not to us.

Yet Rob Gordon’s movie could be in conversation with William Miller’s. They make sweeping proclamations about all the great art that’s been made because somebody couldn’t get laid. Defying all dictates of taste and logic, both films have inspired stage musicals. They each have a take on Peter Frampton: The “Show Me The Way” singer played an essential role in shaping Stillwater’s onscreen presence, teaching Billy Crudup how to play guitar and running a pre-production “rock camp” alongside Heart guitarist and Almost Famous composer Nancy Wilson, who was married to Crowe at the time. Meanwhile, in High Fidelity, Rob overhears Marie covering “Baby, I Love Your Way” as he approaches Lounge Ax. He turns to the guy at the door and asks, with the utmost disdain, “Is that Peter fucking Frampton?”

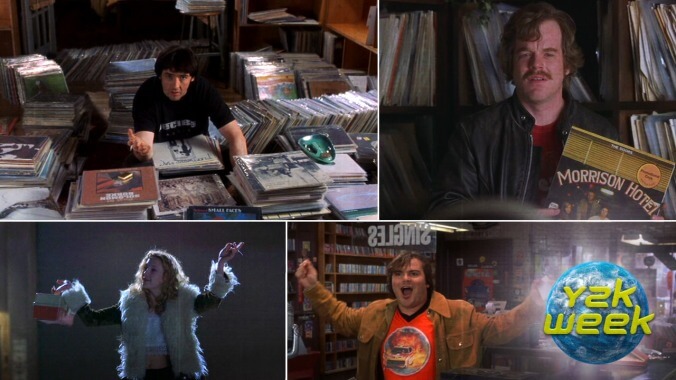

I also have this pet theory that High Fidelity breakout Jack Black could’ve played the Philip Seymour Hoffman part in Almost Famous, and vice versa. The antic energy and self-righteousness with which they imbue Lester Bangs (Crowe’s real-life mentor/sparring partner) and Championship clerk Barry is simpatico. Hoffman’s turn is more soulful and layered overall, but just compare Lester’s physical reaction to “Search And Destroy” with Barry flailing to Katrina And The Waves and tell me the actors couldn’t have swapped places for at least that scene. At the very least, there are overlapping tastes in casting at play: After all, before he moved armfuls of vinyl for Frears, Cusack held up a boombox for Crowe.

It’s serendipitous that High Fidelity and Almost Famous played in theaters during the same year. It’s interesting that it would be the year 2000. A used-record store comedy for a Virgin Megastore age. An expense-account rock-journalism retrospective for the earliest rumblings of the recording industry’s downturn. All those scenes of characters fawning over and coveting pieces of physical media when increasing numbers of listeners were expanding their libraries exponentially on Napster.

Read one way, these attributes point toward a willful retreat from the present day they were released into. Almost Famous has an almost unwavering nostalgia for its period setting, pausing only for dramatic irony (“If you think Mick Jagger will still be out there trying to be a rock star at age 50, then you are sadly, sadly mistaken”) or to underline the power imbalance between a “band aid” like Penny and “golden god” like Russell. The online technologies that had revolutionized so many other elements of daily life in the 1990s had finally come for our music by the year 2000, but the High Fidelity guys are proudly one or two generations behind, passing cassette tapes around and hitching their livelihoods to the seemingly dead format of vinyl records.

But Almost Famous and High Fidelity are uncommonly savvy about music fandom—whether it’s 1973, 2000, or 2020. “Music, you know, true music—not just rock ’n’ roll—it chooses you,” Lester says shortly before waking the good people of San Diego up with a dose of Raw Power. “It lives in your car, or alone, listening to your headphones—you know, with the vast, scenic bridges and angelic choirs in your brain.” (This is how the late Bangs wrote. It’d be unreadable if it weren’t so exhilarating.) Sentiments like this are what bonds the movies most tightly. Using whole passages from Hornby’s first novel (only occasionally de-Anglicizing them), Frears and the Grosse Pointe Blank trio of Cusack, D.V. DeVincentis, and Steve Pink shaped a film that understands the way a song can open your eyes, cut you to the quick, or clasp you by the shoulders and cry “This is it!”

The enthusiasm this inspires takes many forms, even in the space of a feature-length film. There’s the prickly devotion practiced at Championship Vinyl, a dedication to cultivated opinions and aggressive gatekeeping that’s efficiently dismantled by Alex Désert’s Louis: “You feel like the unappreciated scholars, so you shit on the people who know less than you.” (Rob, Barry, and Dick in unison: “No.” Louis: “Which is everybody.” Rob, Barry, and Dick, again: “Yes.” High Fidelity is a funny movie.) Russell “To begin with, everything” Hammond and Stillwater singer Jeff Bebe (Jason Lee) love music so much they’re driven to make their own; for William, Lester, and High Fidelity alt-weekly staffer Caroline Fortis (Natasha Gregson Wagner), the passion comes out in interview questions, printed accolades, or on-air arguments with radio DJs about the proper types of drunken rock ’n’ roll buffoons. The Stillwater guys love playing up the artist/critic divide, but they’re clearly versed in the chestnuts of the rock press: “From the beginning, we said I’m the frontman, and you’re the guitarist with mystique.” (Almost Famous is a funny movie.)

So what, then, to make of Penny Lane, Polexia Aphrodisia (Anna Paquin), Sapphire (Fairuza Balk), and Estrella Star (Bijou Phillips)? It’s in the charitable spirit of Almost Famous that their commitment to the music is taken as seriously as Williams’, or that of Vic Munoz, the endearingly gawky Led Zeppelin follower played by Jay Baruchel. As someone who’s spent his fair share of concerts glancing down at lined paper, I’ve always been mortified by the moment where Penny swipes the pen out of William’s hand mid-notation. As a moviegoer, I love what it says about their differences in philosophy: Reflecting on the music after the fact versus feeling it in the moment. Both are valid expressions in Almost Famous’ eyes, and as the movie plays out, they feed its unique vibe, this lightning that moves the the characters to forego family, friends, and a home that’s not on wheels to re-bottle: The journey William embarks on in his bedroom, Lester’s “angelic choirs,” “the fucking buzz” Jeff describes in an interview, an emotion Sapphire describes as being so strong “it hurts.” I kind of hate how intoxicating I find it, even now.

The superfans of Almost Famous are inspired by people whose paths crossed Crowe’s in the ’70s rock scene, and it’s great that while they’re given jokes (Balk being especially handy in that capacity), they’re never the punchline—they’re different points on the spectrum of rock fandom in addition to colorful personalities populating the Felliniesque circuses of The Riot House and Swingos Celebrity Inn. It’s less great that the movie kind of laughs off how young these characters are, or that Stillwater’s bassist is played by goddamn Mark Kozelek, or that—when he returned to his Almost Famous/Jerry Maguire/Singles wheelhouse after the mindfuck departure of Vanilla Sky—rather than writing another Penny, Crowe went on to conjure up the epitome of a condescending, vexingly persistent cinematic archetype.

Despite bearing some surface similarities to the impish Kirsten Dunst character whose entire reason for being is perking up Orlando Bloom’s deflated Elizabethtown protagonist, Penny is a more complete picture of a person. Partially because Hudson inhabits her character with maximum born-movie-star charisma, but also because we’re allowed to see Penny realize that although she can give her body, mind, and soul over to the music and the people who make it, her affection will never be fully reciprocated. Her OD in a New York City hotel room is Almost Famous’ most glaringly bum note, an unnecessarily melodramatic coda that nearly saps the grace from her and William’s first parting, after she learns that the Stillwater boys used her and the band aids as an ante in a poker game—their value equivalent to $50 and a case of beer. No need for the pharmaceutical fireworks: There’s enough tragedy, epiphany, and dark humor in the half-minute, unbroken shot where Hudson turns from the camera, gathers her composure, wipes away the tears, and asks, “What kind of beer?”

These movies are celebrations, but they sound an alarm, too: Please don’t put your life in the hands of a rock ’n’ roll band who’ll throw it all away. Music enriches the lives of these characters and helps them make sense of their surroundings. But, as an armor against what Penny keeps calling “the real world,” it’s not impenetrable. The Championship credo that “What really matters is what you like, not what you are like” is not to be taken at face value.

It would no doubt delight the characters in these films to know that, although they wouldn’t be smash hits, they would achieve cult-classic status. High Fidelity did modest business opposite March 2000 fare like The Skulls, The Road To El Dorado, and future Oscar contender Erin Brockovich. Almost Famous was a high-profile bust for DreamWorks; Steven Spielberg told Crowe to “shoot every word,” and the price tag for doing so was a $60 million prestige picture whose biggest stars were all on the soundtrack. (Crowe paid the studio back with a healthy awards-season run and an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay on the night Gladiator gave DreamWorks the second of three consecutive Best Picture wins.) The films’ statures would grow with time, DVD releases, and the fondness of viewers who saw their romantic plights reflected in Rob and their ambitions acted out by William—like the white, cishet guy writing this article, which helps explain the positive press High Fidelity and Almost Famous garnered upon release and in the years since. It also explains the gimlet-eyed assessments of their shortcomings, biases, and blindspots that recently culminated in a TV version of High Fidelity that takes place in a post-gentrification, post-Fleetwood-Mac-reevaluation Crown Heights where Rob is a mixed race, bisexual women played by Zoë Kravitz. There’s a lot of postmodern fun to be had with a remake that quotes from the film and the book to such a degree that it cast Lisa Bonet’s daughter in the lead role.

It’s a twist of fate funnier than Sonic Death Monkey turning out to be pretty okay that the two most prescient things about the 2000 version of High Fidelity are

- vinyl making a comeback, and

- the 2020 version of High Fidelity operates in a musical world shaped by the genre agnosticism of Championship shoplifters Vince and Justin.

If only all the modern practices of fandom had inherited The Kinky Wizards’ sense of skate-punk chill. Almost Famous and High Fidelity found their foothold after they left theaters, but their warnings about maintaining separation between yourself and the media you love never really has. If anything, that type of behavior has only gotten worse as the years go by, amplified by social media and monetized by a shrinking number of conglomerates controlling an increasing number of recordings, movies, and TV shows. The internet democratized the collections and the knowledge bases that Rob and his co-workers cited to feel superior to other people, but the gatekeeping didn’t come to an end—it simply mutated into loud, abusive campaigns whenever people who’d been previously shut out of Star Wars, Ghostbusters, or video games asked for access to the clubhouse. The artist has always had a louder megaphone than the critic, but these days the Twitter equivalent of Jeff and Russell bellyaching about Rolling Stone summons armies of unpaid maniacs to their defense. These are broad strokes, but how else do you encompass how intensely weird and scary it is when a largely positive review of folklore can lead to Swifties posting the author’s personal information online? Lest we forget, Y2K’s widest-reaching and enduring depiction of fandom gone too far is Eminem’s “Stan.”

I don’t understand the escalation, but I get where it originates from. I let the chills that ran down my spine the first time I heard “Only In Dreams” lead me down this primrose path of a career. (Zoë Kravitz as Rob: “All white guys love Weezer.” The 2020 High Fidelity is funny, too!) One of the first things I talked about with my future wife was the Pavement button on her jacket. (She knew Stephen Malkmus’ exact age. I was a goner.) I’ve got my own records and turntable now, and I do like to watch them make a few rotations before I step away from the stereo console.

But not as much as I like watching High Fidelity and Almost Famous, my feelings for which have ebbed and flowed with time. To chart it out, it probably looks a lot like my relationship to some of my favorite songs: The intense surge of attachment and identification in the initial exposure, the cooling as flaws are made apparent and the dedication transfers to other works, the long term where they’re valued for their abiding merits as well as their reminders of another time and place—a certain audio-visual security blanket. Years might pass between viewings, but whenever I revisit the films, I still find moments to cherish, or new details I once missed. I see through Rob Gordon’s bullshit now, but I hold tight to this Lester Bangs gem: “The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone when you’re uncool.”