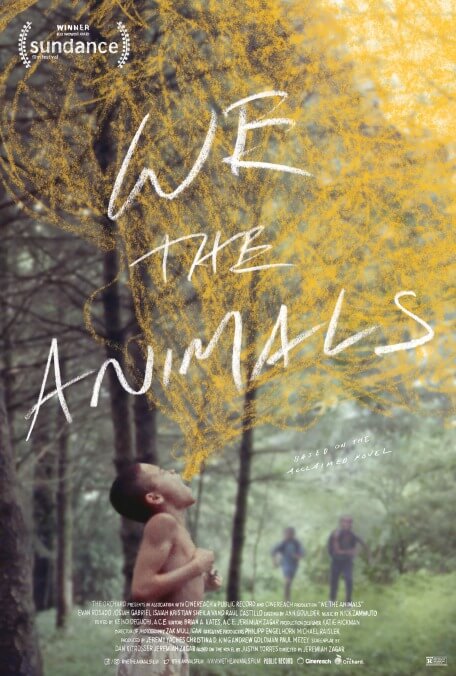

We The Animals offers a little Moonlight, a lot of Malick, and too much coming-of-age cliché

The “we” of Jeremiah Zagar’s We The Animals refers to three young brothers living in the backwoods of upstate New York, some time during the ’90s. Based on Justin Torres’ semi-autobiographical 2011 novel of the same name, the film retains its source material’s predominantly first-person-plural perspective—at least for a while. In early scenes, the boys behave as a single entity in their untrammeled, borderline-anarchic wanderings through the rural landscape. Their parents, referred to only as “Ma” (Sheila Vand) and “Paps” (Raúl Castillo), are intermittent presences at best, often too swept up in their tempestuous, occasionally abusive relationship to pay the kids any mind. Gradually, the youngest brother, Jonah (Evan Rosado), emerges as the story’s protagonist, and it’s that structural shift in perspective—from “we” to “I”—that helps set Zagar’s adaptation apart from scores of generic coming-of-age efforts. A shame, then, that it’s about the only thing that does.

We The Animals, which premiered at Sundance earlier this year, is documentary filmmaker Zagar’s third feature, but also his first foray into narrative drama. Despite his nonfiction background—on full display during the opening credits sequence, which convincingly uses 16mm to replicate the texture and feel of home video—Zagar remains attuned to cinema’s narcotized, dreamy potential. An unexpected time-lapse shot on the night of Paps’ (ultimately short-lived) departure takes the scene from hazy twilight to the blazing glow of day; a woozy sequence renders Jonah’s dreams in monochromatic shades of red, green, and blue. Like last year’s The Florida Project, the film mostly proceeds in free-flowing vignette, fueled by the children’s rambunctious, often destructive sense of play—though here, scenes are punctuated by (at times literal) flights of magical realism and bursts of animation, most of them renderings of Jonah’s sketches, which he keeps in a private notebook hidden underneath his bed.

But unlike Sean Baker, who grounded his Florida Project in a firm but never condescending viewpoint on the milieu, Zagar seems to lack a coherent directorial perspective on Torres’ story; he mistakes vérité-style handheld and frequent close-ups (mostly captured with wide-angle lenses) for genuine intimacy and engagement. A shoplifting episode that has one brother kicking a store worker and a scene of the trio pelting a woman’s car with rocks are both left hanging, never commented on again, and thus relegated to glibly “gritty” detail. Systemic poverty, domestic violence, and casual racism—Ma is white and Paps is Puerto Rican—are all present, but dealt with in a similarly noncommittal manner.

Still, maybe that’s preferable to Zagar’s bungled attempts at evoking the flow of sense memory through sub-Malickian montage, faux-lyrical voice-over, and poetic-sounding dialogue—devices that often come across as secondhand, if not downright embarrassing. (“Why is that light in a cage?” Jonah asks his father. “So it don’t fly away,” Paps responds.) A gauzy, beguiling image of Jonah wrapped in a curtain draws a direct connection to Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher (1999), another sensuous evocation of a working-class child’s loneliness. But it’s a comparison that does Zagar no favors, his attempts at a similar brand of visual/aural disorientation notwithstanding. In We The Animals, the moments that linger are often the most hushed—a rare quality, given Nick Zammuto’s overbearing score—and mainly have to do with Jonah’s burgeoning sexuality. Rosado’s expression of joy after his character experiences a tender, fleeting moment of intimacy late in the film—which Zagar only cuts to after holding for just a few seconds on a distant wide shot—is finely judged.

“Promise me you’ll stay 9 forever,” Ma says to Jonah on his 10th birthday. And it might well be the boy’s own wish—that his life stay suspended in the film’s playground of muffled half-memories. After observing Rosado’s guarded presence across the runtime, however, it becomes clear that Jonah would have to deny who he is to hold onto his life as it is. Not coincidentally, the story’s central metaphor, laid out during a swimming lesson that can’t help but recall a similar scene in Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight, is of baptism: a rejection of a past—here, a family history—in order to embrace a future. Life out of death, in other words. The irony, then, is that Zagar’s vision should feel so disappointingly familiar.