Wes Anderson returns with a densely packed New Yorker homage, The French Dispatch

Meanwhile, Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground documentary blows the roof off of NYFF

“Dense” might be the only appropriate adjective to describe both the New York Film Festival’s complete lineup—which encompasses works from new voices and old maestros, restored classics and uncovered gems, artist discussions, experimental programs, and a bevy of short films—and Wes Anderson’s latest film, The French Dispatch, a visual recreation of an issue of the eponymous weekly, itself a knock-off of/homage to The New Yorker.

Anderson submerges his audience in profound detail from the first moments, which explain the American origins of the magazine and its founder, Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray). Structurally, the film deploys New Yorker-esque section headings to sub-divide three self-contained tales (or “stories,” in journalistic parlance) and a scene report of the publication’s fictional home base, Ennui-sur-Blasé. Actors deliver exposition at the same rapid speed as Anderson delivers visual punchlines. Symmetrical compositions obviously abound, but they rarely linger long enough for anyone to be entranced or annoyed by them. (It’s worth noting that Anderson employs a handheld camera here more often than he has in the past decade.) The sheer number of characters and scenes and incidents will leave even the most attentive viewer dizzy and drunk on style.

Anderson has never been particularly interested in pandering to those disinterested in his particular flavor. Even judged on those terms, The French Dispatch is a niche proposition. There’s the aforementioned sheer concentration of material, of course, but also the unabashed New Yorker fandom (many if not most of the French Dispatch staff have real-life New Yorker counterparts, and at least two of the tales are based on real pieces), the cinematic homages to the French New Wave (especially Godard’s La Chinoise in the second section), and the nostalgic veneration of high/fine/French culture. All of this will either amuse or annoy. Even for those predisposed to his sensibility, the film might look like “one for him.”

Each of the tales and the scene report can be sketchily described as “love letters” to different artistic mediums, but they all feel like romances. The first tale, “The Concrete Masterpiece,” follows an incarcerated painter (Benicio del Toro) who finds his muse in a beautiful prison guard (Léa Seydoux) whose work eventually gains the attention of an avaricious art dealer (Adrien Brody). The second, “Revisions To A Manifesto,” finds journalist Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) on the scene of a May ’68-inspired revolution, tracking the movements of a leading student revolutionary (Timothée Chalamet) and his frenemy (Lyna Khoudri). The third, “The Private Dining Room Of The Police Commissioner,” takes the form of a culinary report by a James Baldwin-esque writer, Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright), which covers a meal prepared by chef and Lieutenant Nescaffier (Stephen Park) for the Commissaire (Mathieu Amalric) that’s interrupted when the latter’s young son is kidnapped by an underworld gang. The common denominator for all of these stories is ardor, either for a person, an art form, a cause, or even just an unexpected event that reinvigorates a passion for one’s reason for living. Anderson exhibits a disarming earnestness for physical and ineffable beauty. Sex, fine art, food, and the written word are all one and the same in The French Dispatch.

Anderson’s films are all comedies on some level, but The French Dispatch takes a MAD magazine approach, stuffing each shot with enough sight gags and visual puns that you could potentially perform a frame-by-frame analysis and still not catch all of them. There’s a general silliness at play here that takes some of the starch out of the film’s premise, like how the student revolutionaries use chessboards as one of many battlefields on which to wage their war, or how the obligatory third-act chase adopts the visual styling of a New Yorker cartoon. Thankfully, it never veers into full wackiness. Nevertheless, Anderson employs a light touch with serious topics, if only to create fluid transitions between scenes and locations, and to not get too bogged down in the melancholic muck.

However, as is the case with all Anderson films, the lightness is deceptive. Each section of The French Dispatch concerns bloodshed in the form of murder, suicide, and war. Beyond the literal violence is a bone-deep wistfulness towards lost ideas and artifacts and people. It’s no coincidence that The French Dispatch covers the magazine’s final issue; finality permeates the entire film. Anderson embraces the past without succumbing to a reactionary stance. He does this by focusing on people reaching out to people and giving them their proper due, either in life or in print.

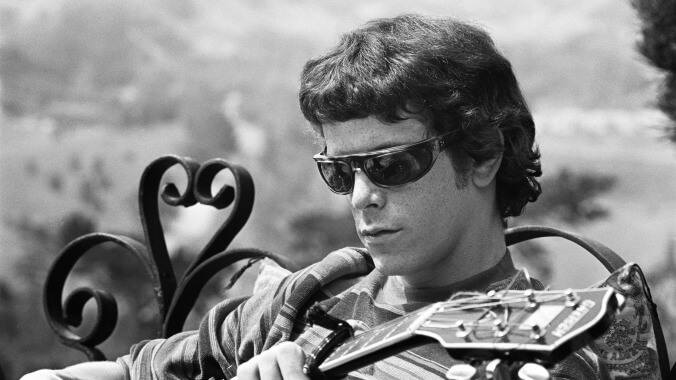

Another film about a bygone era of creation comes from director Todd Haynes (Carol, Safe), whose new documentary The Velvet Underground covers the rise and fall of the eponymous experimental rock band, focusing on Lou Reed and John Cale’s culture-changing friendship and their relationship with Andy Warhol. Yet Haynes doesn’t limit his survey to the band or its members. Instead, he partially uses the story of the Velvets as a springboard to profile the ’60s avant-garde scene in New York, with particular attention paid to filmmaker Jonas Mekas (to whom the film is dedicated) and minimalist composer La Monte Young, whose drone music was a major influence on the experimental art of the era. The Velvet Underground explores “a scene,” one that was fluid, multi-disciplined, and fiercely countercultural.

The Velvet Underground outright rejects the typical form of a music documentary. Instead, Haynes embraces experimental traditions: He takes his primary visual cue from Warhol’s Chelsea Girls by employing split screen, with one side of the frame sometimes featuring selections from Warhol’s Screen Tests and the other side featuring free-floating associative imagery, either archival footage or inspired material. Talking head interviews frequently play over or against the soundtrack; they’re rarely given the floor, so to speak. Haynes follows a chronological timeline (essentially from Reed’s birth up through his last appearance with the group at Max’s Kansas City), but he frequently digresses to paint portraits of the Factory, Nico, some of Reed’s influences (like poet Delmore Schwartz), and New York as a hub of dangerous and innovative artistic movements. The Velvet Underground is less of a Wikipedia article and more of a cinematic treatment of the band as a microcosm of a dam breaking open in American culture.

With that said, Haynes’ film will be manna from heaven for any fan of the Velvets. The film occasionally indulges in hagiography (appropriately so, in this critic’s opinion), but Haynes is much more interested in placing the band in context and illustrating how it embodied ideas brimming in the underground, some of which eventually broke through to the mainstream. “You would need physics to describe this band at their peak,” one person notes near the end of the film, and The Velvet Underground successfully demonstrates why that is while also embracing the limits of light and sound to do them justice. See the film on the big screen if you can. And tell them to play it loud.