What are you reading in April?

In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

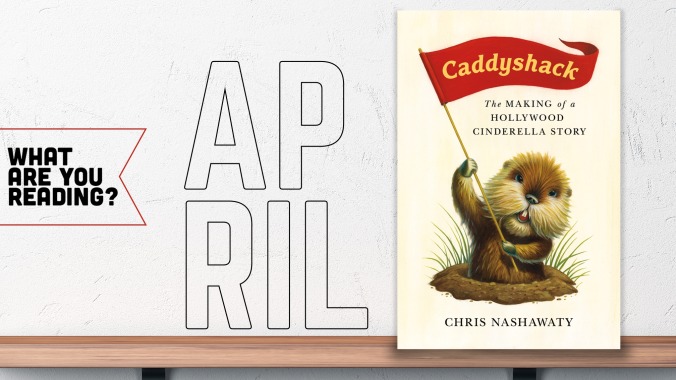

Caddyshack: The Making Of A Hollywood Cinderella Story by Chris Nashawaty

Nearly 40 years after its release, what remains to say about Caddyshack? The story of its hapless, drug-fueled production has become Hollywood legend, and it long ago ascended from critically panned, wannabe Animal House to one of the most beloved and quoted comedies of all time. Longtime Entertainment Weekly writer Chris Nashawaty finds a lot more to say by digging deeper on all fronts. His new Caddyshack: The Making Of A Hollywood Cinderella Story hits the expected marks—behind-the-scenes stories from cast, crew, and executives about the film’s troubled production and release—but particularly shines by creating context. The film doesn’t even get a green light until 100 pages into Nashawaty’s book, the culmination of a process he traces back to The Harvard Lampoon in 1966, where a young writer named Doug Kenney was a rising star. Kenney would go on to write Animal House and Caddyshack, and become a comic legend, and the story of the film is intrinsically tied to him. The book is almost a Trojan horse Kenney biography, but it’s all part of a narrative that explores the seismic shifts in comedy during the ’60s and ’70s that led to Caddyshack. It’d be a lot simpler to talk to the cast and go all Chris Farley Show on them; there are certainly enough funny tales of Caddyshack’s debauched creation to fill a book this size. But the story of a movie that prominently features an animatronic gopher is surprisingly deep and engrossing. [Kyle Ryan]

Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History by Tori Telfer

I am lucky enough to have an independent bookseller in my neighborhood, and luckier still that it’s a place specializing in sci-fi, fantasy, and horror called Bucket O’ Blood. Recently, I’ve been special-ordering books from Bucket O’ Blood to avoid putting any more money into Jeff Bezos’ pocket (every little bit o’ spite helps, right?), which means I wander in there more often than usual. That’s how I came across Tori Telfer’s book, Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History, which has sold out several book-signing events at my local purveyor of all things morbid over the past several months.

Developed from Telfer’s Jezebel column on female serial killers, Lady Killers is well-researched pop history written in a breezy style similar to that of authors like Jennifer Wright and Mary Roach, recounting the lives and crimes of multiple murderesses from Morocco to Kansas, the 13th century to the 20th. Infamous “blood countess” Erzsébet Báthory opens the book, of course, but the most interesting stories are those of lesser-known figures like Mary Ann Cotton, a Victorian woman who took advantage of the high infant mortality rates of her day to poison 11 of her 13 children, and Oum El-Hassen, a Moroccan woman who went from the darling of the French colonial army to a national disgrace within a few short decades. Most of the killers profiled in the book fall into one of three categories—husband-poisoners, sadistic noblewomen, and depraved brothel owners—and while Telfer does a good job of contextualizing how the societies they lived in may have influenced these women, she’s not always as successful in her stated goal of stripping away the sensationalism and titillation that taints contemporary retellings of their crimes. (She critiques 19th- and 20th-century newspapers for emphasizing a murder suspect’s looks, for example, but never fails to mention if one of her subjects was beautiful—or not.) Still, as true-crime junk food, it’s diverting, and occasionally thought-provoking. Why do they call poison a “coward’s weapon,” anyway? As Telfer points out, it takes a strong stomach to handle the cleanup alone… [Katie Rife]

White Noise by Don DeLillo

As is my custom with all of his writing, which is all too long, I recently began David Foster Wallace’s massive, much-praised essay on television, “E Unibus Pluram,” enjoyed it very much for a while, and then lost the thread two-thirds of the way through. (It’s still on my phone and I plan to finish it… someday.) Still, it did contain a block quote from Don DeLillo’s White Noise, a book I’ve often sort of thumbed through curiously without ever really planning to read, and, brief as the excerpt was, it was funnier and tighter and more moving than I’d expected, documenting a weird road trip to see a tourist attraction that turns into a meta-commentary on spectatorship and objective reality. So I bought the book, on a whim, and found to my delight that the whole damn thing is like that.

My previous experience with DeLillo consists of an abortive attempt to read Libra when I was in like middle school or something. I distinctly remember nothing quite adding up then, which may well have been the point, but now, perhaps thanks to Wallace’s framing in the essay, or perhaps because White Noise is a better and clearer novel, I find myself sort of freaking out about the profundity of an individual phrasing or passage every few pages. The first section of the book is a series of short chapters that each play out like elliptical pieces of short fiction, detailing the cozy life of an aging academic and his large family. But it’s peppered with notes of surrealism and despair, like the protagonist’s area of expertise (Hitler Studies) or the juxtaposition of marketing language and advertisements into deep existential musings. And, bleak as all this is, it’s funny as hell, with snappy, circuitous dialogue, and descriptions like this one: “The landlord was a large florid man of such robust and bursting health that he seemed to be having a heart attack even as we looked on.” DeLillo fires these jokes off like they’re nothing, but thanks to the tight structure of the book’s first part, they each have room to breathe, a weight of their own.

As of the other night, I have entered the book’s second section, where things turn apocalyptic and lyrical but still blackly comic. If you, like me, have slept on it as a should-read novel that lacked much appeal outside of some objective importance, I recommend it heartily. All of that importance may’ve obscured some of its original charm, which, among other things, is an immensely reader-friendly, pitch-black comic invention. [Clayton Purdom]