What are you reading in April?

In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

Ways Of Hearing by Damon Krukowski

It’s odd to read a book adapted from a podcast. And surely Ways Of Hearing produced a trippy meta effect in its original medium, too: Damon Krukowski’s short-run Radiotopia program used a digital format to talk about some of the things lost in the transition to digital formats. But as someone who rarely listens to podcasts, I had no reference point going into MIT Press’ new print version, and I’m glad to say it didn’t diminish my enjoyment at all. Rather, because the book reads like an illustrated script, complete with sound-effect and scene-setting embeds, the narrative played out vividly in my mind.

Ways Of Hearing explores five different aspects of listening in the digital age: time, space, love, money, and power. With anecdotes from his lifetime playing in bands like Damon & Naomi and Galaxie 500 and conversations with artists like Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Downtown Boys, Krukowski tells an engaging and important story about what we lose to digital convenience—the vocal nuance in cellphone mics, for example, or the element of surprise in record stores to curated streaming services. I especially appreciate that Ways Of Hearing challenges these popular assumptions about technology and music with zero judgment or analog snobbery. Krukowski talks a lot about how things used to be done, naturally, but with very little nostalgia. He comes off simply as a human being who hopes to stay grounded in a noisier, more enriching world—one unfiltered by algorithms and echo chambers. I happen to want to live there, too.

At 133 pages, it’s a breezy but thought-provoking read, where the subversive spirit of the text carries over to the book’s design. Like its podcast predecessor, the print edition is heavily influenced by John Berger’s Ways Of Seeing, and makes really fun use of layout and typesetting. It’s definitely the first book I’ve read where the text started right there on the cover. [Kelsey J. Waite]

“Notes On Nationalism” by George Orwell

“Nationalism” can be a slippery term to define. George Orwell’s definition differs from the established one, and it differs from the very modern “alt-right” branding of white nationalism present today, but his conceptualization is still extremely relevant in 2019. (Really, it might be helpful to think of it as a new term that describes its own specific set of beliefs.) Although he published his essay “Notes On Nationalism” in 1945, its core tenets are so startlingly applicable to what’s happening today it’s a bit astonishing.

Broadly, his nationalism starts with “the habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad.’” But, more importantly, nationalism is “the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests.” This is what makes nationalism, in Orwell’s understanding of the concept, different from patriotism, or party loyalty, or religion. It’s less a rigid set of beliefs than an alignment with one side that comes with a self-deception inherent in believing that one’s side is better, stronger, and more powerful than the other side, even in the face of facts to the contrary.

Does this sound familiar? Reading “Notes On Nationalism” provides a sound framework for understanding how Trump and his supporters operate—their psychology and absolute loyalty not to a set of principles, but to their own side, whatever that happens to mean that day. Early on in his bid for election, many thought that Trump’s capriciousness would eventually turn the Republican congresspeople and base against him—he was too erratic and impulsive for politicians campaigning on an established set of principles. We know that’s not how it turned out, and that his followers continue to support him despite his temperamental style of governance. It’s what makes the unwavering loyalty all the more baffling. A preoccupation with defending him against detractors comes with an enormous amount of hypocrisy and self-inflicted blindness to reason, fact, or morality; whatever he does is the center of what is right. But these qualities, inexplicable on their face, are part and parcel of the nationalist in Orwell’s interpretation, as he goes on to describe habits of nationalism through three key traits: obsession, instability, and indifference to reality.

On obsession: “As nearly as possible, no nationalist ever thinks, talks, or writes about anything except the superiority of his own power unit. […] The smallest slur upon his own unit, or any implied praise of a rival organization, fills him with uneasiness which he can only relieve by making some sharp retort.” Think Ben Shapiro and his ilk on Twitter and the red-faced men who bellow on Fox News. And, of course, Trump himself.

On instability: “The intensity with which [the nationalist’s beliefs] are held does not prevent nationalist loyalties from being transferable […] God, the King, the Empire, Union Jack—all the overthrown idols can reappear under different names, and because they are not recognized for what they are they can be worshipped with a good conscience. Transferred nationalism, like the use of scapegoats, is a way of attaining salvation without altering one’s conduct.” This is what some of the anti-Trump Republicans decry: the move away from “traditional” Republican beliefs and into something Reagan would find unrecognizable, supposedly, which is following the president’s every whim and vagary, no matter how random, cruel, or damaging to the future of the party it might be. The fervor these politicians once held for the “party of family values” was easily transferrable to a psychopath. That much is clear.

And lastly, indifference to reality: “All nationalists have the power of not seeing resemblances between similar sets of facts.” What Orwell’s getting at is hypocrisy. Wrongs committed by my side are moral, or not worth commenting on at all, while wrongs committed by the other side are worthy of an enormous amount of indignity. It is Republicans and right-wing pundits losing their shit over Hillary Clinton’s emails, or Al Franken’s sexual misconduct allegations, while ignoring equivalent and much worse conduct on their own side. “Actions are held to be good or bad, not on their own merits but according to who does them, and there is almost no kind of outrage—torture, the use of hostages, forced labour, mass deportations, imprisonment without trial, forgery, assassination, the bombing of civilians—which does not change its moral colour when it is committed by ‘our’ side.”

Again, it’s crazy that Orwell wrote this more than 70 years ago, when it applies so readily to the Fox News Trumpian presidency we’re living through.

There’s more to the essay—a passage describing how the nationalist is “haunted by the belief that the past can be altered” is also a readily applicable one, thinking about the seemingly upward trend of people denying the Holocaust happened. (Something Orwell describes happening in real time! In 1945!) My copy of the essay is in a little Penguin Classic book, bound with two more Orwell essays (“Antisemitism In Britain” and “The Sporting Spirit,” the latter of which is surprisingly relevant to “Notes On Nationalism”). The essay is also available online through the Orwell Foundation. Read it, and marvel like I did. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

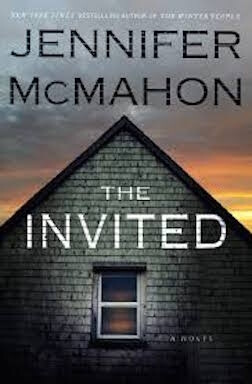

The Invited by Jennifer McMahon

I’ll watch just about any old crappy horror movie, but it takes a lot more to get me to check out a book that may be similarly trashy—like a subpar video game, the time commitment is simply too large to waste it on something generically forgettable, not when I could be reading W.G. Sebald, or something. (Okay, that sounded pretentious, but you’ve gotta admit, The Rings Of Saturn beats most challengers for your time.) But The Invited had one hell of a hook, one that got me to look past the possibility of it being a pulpy slice of cheese I’d regret picking up: Instead of a wide-eyed and earnest couple unwittingly moving into a haunted house (yawn), the book tells the story of a husband and wife who essentially set out to build one from scratch.

Not at first, of course: Helen and Nate Wetherell simply want to live out the dream of moving to the countryside and building their ideal rustic home, doing the whole back-to-nature thing. But Nate wants to buy local, and Helen wants a connection to the history of the land they’ve bought, folk tales and all. So she starts incorporating artifacts from the town’s past, picked up from resale shops and aided by local color, that just so happen to have ties to the darker moments of her land’s history. Building a haunted house is such a deliciously fun spin on the trope, and thus far I’ve been devouring it. McMahon’s prose is clean and unfussy, with a steady attention to tension that actually worked on me—I don’t get scared by horror novels much anymore, but a scene of something otherworldly unfolding in the night actually gave me goosebumps. I’m finishing it tonight, possibly with plans to leave reruns of Frasier playing on TV afterward to help me fall asleep, if it keeps creeping me out like this. [Alex McLevy]