In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

The holiday season is one of my favorite times of the year, full of magic and joy and presents and goodwill toward men and all that crap. So naturally my reading tastes around now start trending toward analyses of why we’re so filled with hate and anger the other 11 months. Hence my interest in The Monarchy Of Fear, political philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum’s new book exploring why she believes fear to be at the root of so many of the problems illuminated by our current political situation in the United States. Working from the premise that emotions always undergird our political beliefs—to a far greater degree than most of us would likely care to admit—she traces the effects of fear on the climate we see around us every day, arguing that anger, disgust, envy, sexism, and other visceral responses we wouldn’t normally consider fear-based are, in fact, connected to that fundamental emotion.

The book has the unfortunate subtitle “A Philosopher Looks At Our Political Crisis,” which makes it sound as though the whole thing is an eye-rolling exercise in ponderous and simplistic digressions along the lines of “So America in 2017 seems to be a lot more anti-Semitic than it was in previous years! Let me tell you what Aristotle would say.” Thankfully, Nussbaum mostly avoids such trite correlation, instead focusing on psychological case studies and hard data from which she extrapolates arguments about the reasons people turn to seemingly irrational political positions, be they anti-immigrant or religious bigotry. (When ancient philosophers do appear, it’s in the service of sharp and insightful rhetoric about the human condition.) Her chapter on anger is especially powerful, performing a valuable auto-critique on self-righteous leftist positions that seek retribution rather than positive justice. “People may think anger is powerful, but it always gets out of hand and turns back on us. And, yet worse, half the time people don’t care,” she writes. “They’re so deeply sunk in payback fantasies that they’d prefer to accomplish nothing, so long as they make those people suffer.”

It’s not without its failings; those looking for a deep dive into theory will find themselves underwhelmed by the broader-based general audience Nussbaum is addressing. And she can get a bit touchy-feely at times, playing the role of the optimistic progressive in a way that could irritate those of a more radical persuasion. Still, it’s thoughtful and engaging stuff, and a more astute stating of the case than you’ll get from yet another op-ed bemoaning the American conservative voting against their own self-interest. [Alex McLevy]

I received a copy of the 10th anniversary special edition of Patrick Rothfuss’ The Name Of The Wind last year, and I’ve just finished its 700-plus pages. It’s a re-read for me, but no matter. It’s always worth revisiting Rothfuss’ sumptuous, extravagant prose, and this extra-thick, red-trimmed-page edition contains some extremely interesting additions from the author. There are nuts and bolts explanations about the formation of the Aurturian empire, its calendar (a “span” is 11 days!) and currency systems, and a lovely, meandering author’s note from Rothfuss.

As for the story itself, I always find a little more to love when I go back to the as-yet unfinished Kingkiller Chronicle trilogy. The final lines of the first two books remain a personal favorite: “It was the patient, cut-flower sound of a man who is waiting to die.” I’ve also come to appreciate how Rothfuss grapples with money and class concerns in his made-up world, one of the only fantasy writers I’ve read to do so. Main character Kvothe is constantly scrounging, toiling, plotting, and bargaining to make ends meet, thinking about and borrowing money to survive.

There are some scenes that stretch on too long, with a bit too much melodrama and sentiment for my taste. Regardless of minor quibbles, the book is still worth reading to enjoy the poetry of the prose. That’s another thing I noticed on this re-read that I hadn’t before: Rothfuss’ Kvothe is a trouper and singer who bashes poetry as an art form several times throughout the story, which is pretty funny considering how much poetry his writer puts into every sentence. [Caitlin PenzeyMoog]

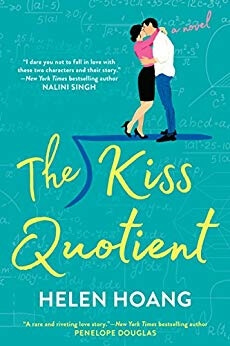

It became clear to me recently that my virtual stack of books to read was looking more and more like a chore and less like fun. Encouraged by an episode of the delightful podcast Reading Glasses (episode 37, titled “Drop That Book Guilt And A Review Of A Plastic Bag”) that gave some specific tips on rediscovering the pleasures of reading, I decided to try something I’d never done before: read a romance novel. The Kiss Quotient had been recommended by some Twitter friends, it was available as an e-book from the Chicago Public Library, so why not? I consumed the entire book in an afternoon, itself a pleasure I haven’t had in some time, and it was exactly what I needed to reclaim some joy in my reading. Sure, the happy ending is predictable, but Helen Hoang’s writing is quick and smart, the main characters are multidimensional, and even if their problems are heightened for the sake of the narrative, they’re still relatable at their core. The plot was inspired by Hoang’s desire to write a take on a gender-swapped Pretty Woman: Protagonist Stella Lane has autism spectrum disorder, but is determined to take control of her love life, and hires a male escort to give her the relationship and sexual experience she thinks she needs in order to start dating. You can already guess what happens, but it’s so enjoyable that I was happy to spend an afternoon lost in Hoang’s narrative. Stella is written sensitively but not pityingly, and the book’s progressive values are handled with an extremely light hand. And no, there are no enameled pepper grinders in Hoang’s well-written sex scenes. [Laura M. Browning]

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.