Tommy Orange, “The State”

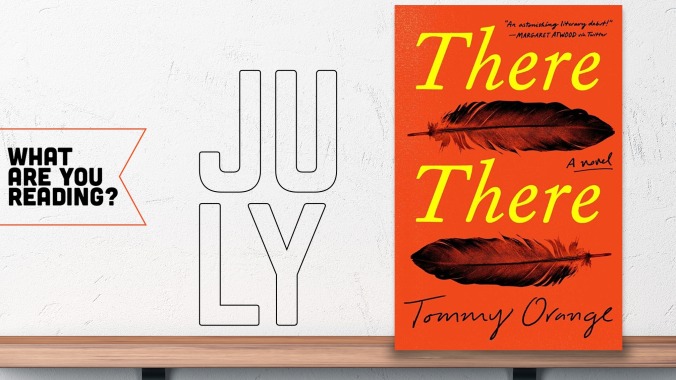

I’ve never read someone attempt a sustained piece of fiction in the second person, but Tommy Orange’s “The State,” recently published in The New Yorker but pulled from his buzzy debut There There, pulls it off with aplomb. Unlike most other second-person writing I’ve read—internet how-tos, poorly structured hypotheticals—it tells the story of a remarkably specific “you,” a bulky and bruised young man of mixed Cheyenne and white parentage. He—“you”—grapples mightily with booze, with biology, and with the slowly gentrifying city and subway stops of Oakland, California, all via Orange’s taut, pugnacious prose, whose paragraphs mount together vast assemblages of ideas into weird, unruly monuments. For all the specificity of the story’s subject, the piece is ultimately concerned with something universal, its titular “state” one of meditative blankness, where all the ragged and thorny and painful parts of a person’s history—his, yours, whoever’s—drop away. [Clayton Purdom]

Nafissa Thompson-Spires, “Fatima, The Biloquist: A Transformation Story”

“Fatima, The Biloquist: A Transformation Story” is warm, smart, and full of contradictions. It’s described as a short story “sketch,” but there’s nothing cursory about it. Nafissa Thompson-Spires loads her briskly paced and bitingly funny story with details about her characters, Fatima—who learns to speak from both sides of her mouth, i.e., either side of the cultural divide between black and white—and Violet. Her imagery is so evocative, you can easily picture both girls as their friendship blooms and withers, from their first meeting at a makeup counter to that devastating kiss-off in a mall courtyard. Just like its namesake, “Fatima, The Biloquist” speaks in two languages: one full of cultural signifiers, that can speak to Heads Of The Colored People’s exploration of U.S. black citizenship, and one that’s more ambiguous, more universal. The short-lived “platonic romance” between Fatima and Violet will resonate with most readers, but Fatima’s observation that proximity to blackness (see: the Kardashian-Jenner clan) is often more advantageous than being black in this society is found between the lines. Certain phrases have multiple connotations, secondary meanings seemingly composed of invisible ink, that are only revealed with the right light. Like the rest of the stories in Heads Of The Colored People, Thompson-Spires’ debut collection, “Fatima, The Biloquist” is an engrossing read—in any language. (Note: as is often the case, the story as it appears online probably differs from the version published in Heads Of The Colored People.) [Danette Chavez]

Nick White, “The Exaggerations”

“The Exaggerations” by Nick White begins as an archetype: a story about storytelling. The narrator’s uncle liked to tell stories, and he liked to exaggerate when he told them. Thus the fiction we’re reading unfolds, the narrator repeating Uncle Lucas’ inflated tales, sometimes revealing their embellishments, other times letting their mysteries remain. Along the way, the rest of their lives in the Delta are shaded in: When the narrator was 14, he lived with his Uncle Lucas and Aunt Mavis, his country singer mother having left her son in hopes of making it in Nashville. The narrative centers around one night in which Uncle Lucas took his nephew out to a ramshackle bar in the woods to a bachelor party of sorts for his best friend. It’s a rich, layered story (a version of which appears in White’s collection Sweet And Low) filled with details of living in the South among men who feel the need to hide some of the most essential parts of themselves. Uncle Lucas’ penchant for exaggeration and the subsequent debunking of those tall tales sets up the expectation for a great demystification. Instead it’s the story he doesn’t tell, about himself and his sexuality, that’s the most powerful. Just when it seems like the narrator is at risk of indulging in an exaggerated sentimentality, one he has not before expressed, White pulls the story taut, and readers learn that the narrator may have inherited more from his uncle than just loneliness. [Laura Adamczyk]

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)