What are you reading in March?

In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

Katie Rife

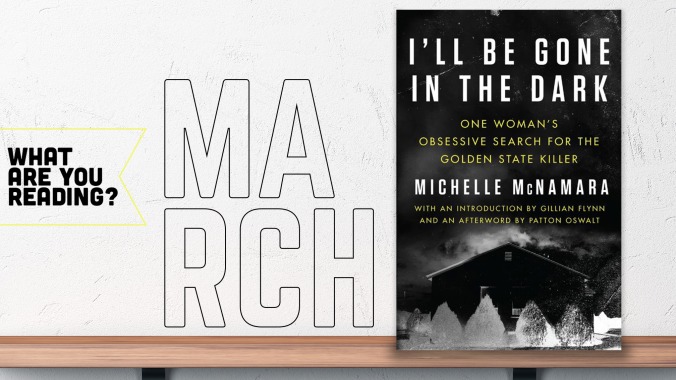

When Michelle McNamara died suddenly in the spring of 2016, many knew her only as the wife of comedian Patton Oswalt. But McNamara was also an eloquent writer, a dogged investigator, and a deeply empathetic soul. All those qualities are on display in her book I’ll Be Gone In The Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search For The Golden State Killer, McNamara’s magnum opus that was published posthumously at the end of February.

McNamara describes the relationship between a mother and her errant daughter with the same intense interest as she does a bloody crime scene or a new forensic technique, and her prose comes alive when describing the hopes, dreams, and personal relationships of the people whose lives were tragically cut short by the Golden State Killer who terrorized California in the 1970s and early ’80s. You really get the impression that you’re seeing someone’s life’s purpose written out on the page, a feeling that’s enhanced by McNamara’s occasional detours into memoir, like the chapter about her childhood in Oak Park, Illinois, and the unsolved murder of one of her neighbors that sparked her interest in true crime.

McNamara’s investigation into the identity of the Golden State Killer was still ongoing when she died, and parts of I’ll Be Gone In The Dark are pieced together from her notes. It’s both sad and frustrating to think about what might have happened if she had lived to finish her work—could she have finally found the man who killed at least a dozen people and raped 50 more, or was this destined to remain an unsolved mystery either way? That question will never be answered, but at least we have this book, a monument to both Michelle McNamara’s life and those of the victims she wrote about.

Kyle Ryan

It’s taking me longer than expected to finish Stephanie Wittels Wachs’ Everything Is Horrible And Wonderful: A Tragicomic Memoir Of Genius, Heroin, Love, And Loss. I do most of my reading before I fall asleep, but after three semi-sleepless nights brought on by the book, I decided to ban it from bed. The insomnia came not just from a desire to keep reading Wachs’ book, but also—mostly—from its powerfully affecting and upsetting story. Wachs is the older sister of Harris Wittels, a comedian, writer, and A.V. Club favorite who died from a heroin overdose in February 2015. It’s a sadly familiar story, but not easily dismissed as yet another tragic comedy casualty. In her book, Wachs bounces between the past and the present aftermath of Wittels’ death, writing to him directly as she endures the grieving process, the duties that accompany being the executor of his estate, and the demands of being a new mother. It’s a shitshow, as Wachs poignantly elucidates in her emotionally raw prose. Because she’s also a performer and her subject is, as Sarah Silverman described him, “the funniest boy in world,” Everything Is Horrible And Wonderful also has laugh-out-loud moments, such as Wittels’ set notes from his final show and Wachs’ sardonic observations about her family’s new reality without him. Still, the book’s haunting details linger, like the Airbnb page on Wittels’ laptop when his body was found, or learning that, during rehab, he’d refused a prescription that would’ve prevented him from getting high. As she tries to understand what happened, she comes to realize how powerless she, her family, and Wittels’ friends were to save him. It’s the kind of thing that can keep you up at night.

Caitlin PenzeyMoog

In an effort that will probably end up taking decades, I’m slowly making my way through the female-written books that won and were finalists for the Pulitzer in fiction. The latest entry is Laila Lalami’s The Moor’s Account, a novel whose somewhat mundane-sounding title belies a rich, vibrant, and engrossing story about the first African explorer of the Americas. Lalami based her fictional account of the eponymous Moor, Mustafa, on the true story of the 1527 Narváez expedition. This Spanish mission to colonize Florida ended in disaster, with only four members of the original 600 or so surviving. In historical documents chronicling the surviving four, one was described simply as “an Arab negro,” and it’s this character that Lalami turns into the protagonist of The Moor’s Account. Using a past/present plot device, Mustafa’s journey to Florida as a slave is interspersed with his past, first with his childhood and young adulthood in Morocco, then as a slave in Spain. Lalami is a diligent researcher, who understands how to make history a vital part of her world-building without turning a novel into a history textbook. She successfully makes three very different settings come alive: that of Mustafa’s childhood and young adulthood spent in a thriving town in Morocco; the Spanish city he spends wretched time in as a slave; and the New World, one made remarkable for how it looked before colonizers destroyed the Indigenous populations and altered the landscapes.