What are you reading in October?

In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

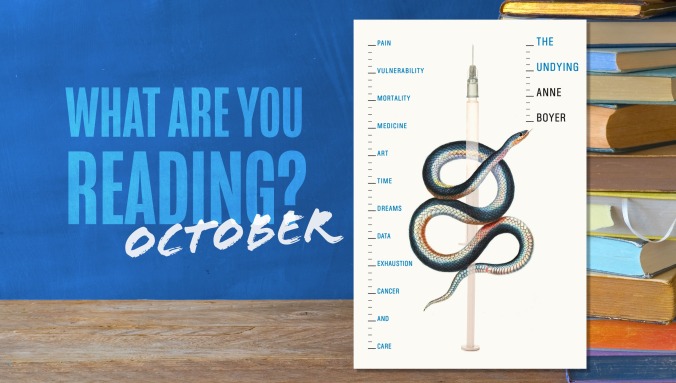

The Undying by Anne Boyer

In Michael Martone’s 1991 short story “It’s Time,” a woman ravaged by radiation from her work in a clock factory picks raspberries in her yard. “I thought about sucking the raspberry into my mouth, straining it through what was left of my teeth,” Martone writes. “I found a pencil and a piece of paper to write this down. Each word fell on the page, a burning tongue.” There is a similar immediacy—spurred by bodily deterioration and mortality—in Anne Boyer’s The Undying, a meditation on illness and its debilitating cures. As in her previous books Garments Against Women and A Handbook Of Disappointed Fate, Boyer’s righteous anger rises to the fore within direct, precisely wrought prose, here prompted by her diagnosis and treatment of highly aggressive breast cancer (“Fingernails lifting from fingers hurt as badly as fingernails lifting from fingers should”; “Our genes are tested: our drinking water isn’t”). The book is one of resistance—not only against a capitalist system that saw Boyer still going to work, despite being so weakened from chemotherapy that she could barely walk, because she had run out of sick days, but also familiar manifestations of the breast cancer story, its clichés of epiphany and pink-ribbon inspiration. “People with breast cancer are supposed to be ourselves as we were before, but also better and stronger and at the same time heart-wrenchingly worse,” she writes. “We are supposed to keep our unhappiness to ourselves but donate our courage to everyone.” Near the end of the book, now among the “undying,” she says, “it was clear that when I was at my lowest, what I needed most was art—not comfort.” In turn, art, not comfort, is what Boyer has tendered here. [Laura Adamczyk]

The Year Of The Monkey by Patti Smith

Maybe it’s because she herself came into the world around New Year’s Day—a time of renewed expectations and possibility—but Patti Smith seems to live her days with inexhaustible hope. It’s part of why the The Year Of The Monkey, which follows the melancholy, chaotic year leading up to Smith’s 70th birthday, is so intriguing: Beyond her prolific and charming Instagram posts, the “self pictures” and set lists, what does the modern world look like to Patti Smith, shamanistic punk poet who still works the idealist anthem “People Have The Power” into nearly every performance? It is surreal, for one. In The Year Of The Monkey, time and reality are permeable, seasons and settings blurring as Smith travels down the California coast and back home to New York City, then to Kentucky and Europe for short stints. It’s not always clear where she will wake up, or when she does, who or what around her really exists; a talking hotel sign or a mysterious acquaintance named Ernest stand in for a host of uncertainties, filling silences on the road.

Smith’s world is increasingly lonely, too. In M Train, she wrote about the succession of untimely deaths of her husband, brother, and dear friend Robert Mapplethorpe. The Year Of The Monkey finds her reckoning with a new kind of loss: peers who are dying because they’re aging. It’s when she’s remembering these loved ones that Smith’s writing is most powerful—memorializing the late Sandy Pearlman and Sam Shepard with elaborate, shrinelike visions—and in stark emotional moments, like when she dazedly walks the streets of NYC on election night 2016. The Year Of The Monkey doesn’t attempt any grand political statement or “for our times” lesson, as marketing materials might’ve suggested. In her relentless curiosity and commitment to her craft, Smith offers an example of humbly, passionately doing what she can. “I’m just a writer,” she offers wearily to Ernest near the narrative’s end, “nothing more.” [Kelsey J. Waite]

Inside Out by Demi Moore

When a new celebrity memoir comes out, everyone usually cuts straight to the scandalous stories. In Demi Moore’s new autobiography, Inside Out, those anecdotes include her mistaken belief that she took Jon Cryer’s virginity (Cryer tweeted, “she was totally justified making that assumption based on my skill level”) and the post-partying 911 call that landed her in the hospital and back in the headlines at the age of 49. But Inside Out’s best chapters chronicle events before her famous husbands show up. Moore candidly reveals a multitude of painful stories from her past, starting with an extremely unstable childhood with her alcoholic parents. At times it’s not an easy read, but Moore’s unflinching sincerity usurps any sensationalism. As she puts it, in a typical example of the book’s winning prose, “Putting it all down in writing makes me realize how crazy a lot of it has been, how improbable. But we all suffer, and we all triumph, and we all get to choose how we hold both.” [Gwen Ihnat]