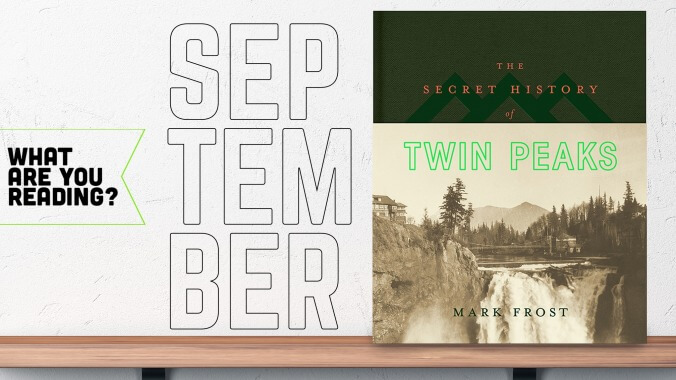

You can count me among the throngs of bewildered viewers who’ve fallen further than ever into the deep, confusing, and ultimately unknowable lore of Twin Peaks thanks to The Return. As part of my preparation for the big finale, I checked out Mark Frost’s The Secret History Of Twin Peaks from my local library, and I’ve been poring over it like mad. It takes the form of a document-filled dossier that’s been assembled by a mysterious archivist and reviewed by an FBI agent who shows up in The Return. As the title implies, it’s an all-encompassing look at the history of Twin Peaks and the paranormal phenomena that have haunted those lands for centuries.

When the book was released in late 2016, there was some consternation about Frost’s willingness to play up the UFOs and aliens that crept around the fringes of the show during season two, even going so far as to imply that they might explain all the town’s mysteries. But reading this book after watching The Return, that criticism seems horribly shortsighted. Frost invokes those elements, but they’re a red herring, an easy-to-grasp explanation for entities and events that The Return makes clear are far beyond humanity’s understanding of the universe. What Frost does provide are some details that presage a few of the season’s weirder character turns, like why Dr. Jacoby is now suddenly running a politically charged radio show, and more intriguingly, a lot of fascinating little hints that recontextualize some of the biggest, strangest enigmas that emerged over those 18 episodes. No, there aren’t any answers here, only lenses through which new questions are formed, and that’s exactly the way anything Twin Peaks-related should be. As Major Briggs says in one of the book’s recounted conversations, mysteries are “the essence of our existence, and aren’t necessarily meant to be fully apprehended.”

Caitlin PenzeyMoog

I recently devoured Jac Jemc’s The Grip Of It in a little under two days. I’ve never read much horror fiction, but I can’t imagine it gets much better than this. Jemc crafts a singularly spooky haunted house tale that, on the surface, is rote horror: A young couple dealing with some marital issues moves away from the city and into a strangely affordable home. The house has a past, of course, and not only does it haunt the couple, but it slowly turns them against each other, too, until neither can be quite sure of the other. The earlier relationship strife becomes key to their burgeoning mistrust.

I was legitimately scared during certain passages, as though I were watching a horror movie by myself with the lights out. This isn’t news to anyone who’s enjoyed a legitimately scary book but—it’s nuts! The act of reading something scary versus watching it unfold in a film makes for a much deeper sense of horror. Whereas I can look away from the screen during a scary scene and locate myself in the theater or room—thereby pulling myself out of the fiction to make the scariness less scary—reading a book as propulsive as The Grip Of It rendered me unable to look away, as it were.

I have minor quibbles with some of the book, namely that the characters are underdrawn and at times clichéd, especially Julie, who falls into the type-A analytic stereotype of lots of women in pop culture. But since when does a good horror story need to include a character study? Leaving the main characters as mostly blank slates doesn’t lesson their—and the reader’s—scares.

Kyle Ryan

I started a Studs Terkel kick a couple of months ago after flipping through a copy of Division Street: America at the Chicago History Museum. (Add a Cubs jersey and some deep dish, and that sentence would’ve been the most Chicago thing ever.) For the uninitiated, Terkel was a Chicago journalist and broadcaster, best known for his oral histories. These aren’t oral histories as we’ve come to know them—i.e., interviews with the people at the center of some phenomenon—but open-ended talks with everyday people about their experiences, collected under a theme: World War II (“The Good War”), the Great Depression (Hard Times), race (Race), work (Working), etc.

Prior to this, I’d only read The Good War, which won a much-deserved Pulitzer in 1985. What struck me about people’s stories of life during wartime was how ambivalent many of them felt. Seventy years later, it’s easy to picture Americans uniting behind a war effort to defeat evil, but plenty of people in Terkel’s book weren’t sure about it. The quotation marks in the title reveal that a bit: People called WWII “the good war” because they thought it was just and necessary, but even then, Terkel says, it was still a war—which is never “good.”

I started with Terkel’s first oral history: 1967’s Division Street: America. Although named after a Chicago street, the book took Terkel all over the city in the early ’60s. Unsurprisingly, a lot of people had civil rights and race relations on their minds. Fifty years later, it’s still startling to hear people talk about civil rights marchers as troublemakers, or in one person’s case, dismiss Martin Luther King Jr. as a demagogue. Numerous people describe the serious consequences of black and white people simply being friendly to each other. That remains timely in 2017, as does this quote from sixtysomething Lois Arthur, who sounds like Trump: “Chicago is a lost town. It’s too big and too out of hand. Nobody can live in Chicago and feel like they’re living in a place where everything’s going to be all right. Everything’s wrong in Chicago, everything.”

Following Division Street, I picked up Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day And How They Feel About It from 1974. Although The Good War won a Pulitzer, Working is the Terkel book I’ve heard about the most, and with good reason: It’s a 640-page dive into the work lives of people from around the country, across the professional spectrum. This one will take me all of September and October to read, but the chapters about a migrant worker and miners have once again reminded me of how very, very easy I have it.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)