What are you reading in September?

In our monthly book club, we discuss whatever we happen to be reading and ask everyone in the comments to do the same. What Are You Reading This Month?

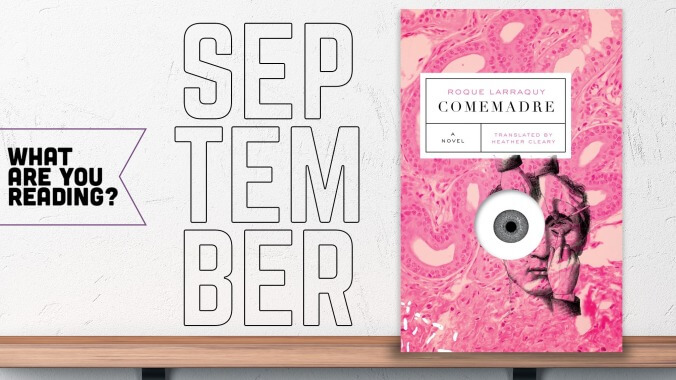

Comemadre by Roque Larraquy (translated by Heather Cleary)

I often read what end up becoming some of my favorite books when I’m supposed to be reading something else. I don’t plan it; it just happens. It’s akin to saying you’re too busy to attend a friend’s party, only to run into an acquaintance on the street that night, someone you wish you knew better, and then eating and drinking and talking with them for hours, making a whole night of it. You can’t help it; you’re having too good a time. This is how the novel Comemadre came to me, when I was in no position to start something new. And yet, after a few trusted readers mentioned it and I saw its bright pink cover in a local bookstore, soon enough I was buying it, then reading it, then talking my friends’ ears off about this weird little novel in which people get their heads chopped off—for science—in rural Argentina. Comemadre, the first book by Argentinean writer Roque Larraquy to be published in English, is split into two parts. (The translation slips in a few puns.) The first focuses on a sanatorium outside of Buenos Aires near the turn of the century, where a group of doctors decapitate select patients, hoping that in the few seconds the severed heads continue living without their bodies, they will reveal insights into the afterlife. In the novel’s second part, set 100 years later in the city proper, a conceptual artist creates increasingly bizarre, and grotesque, art installations. There’s a lot going on in this slim novel (a potent 130 pages): doppelgängers and doubling, mutilation, lust, macho posturing, and a self-eating plant as central metaphor. Even as the plot remains brisk—the dialogue is unbelievably snappy in places—Larraquy never loses sight of his heady interests: what happens when art and the body meet, and how men’s inflated egos and desire for sex and renown can result in both transcendence and destruction. It’s a hilarious, mildly gory novel, refreshing in its humor and strangeness—the perfect thing to read when you should be doing something else. [Laura Adamczyk]

The Flame by Leonard Cohen

I go through spells with Leonard Cohen. When I first picked up his 1967 debut, Songs Of Leonard Cohen, in a Memphis record store more than a decade ago, I spent an entire winter warming myself by its melancholy glow, putting it on in the mornings to let its spare, radiant arrangements fill my apartment as I sipped my coffee and welcomed the day. As clear as ever, I can still hear the boats going by Suzanne’s place, see the “hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm.” When I’m reading or listening to Cohen, his perspective on life and even his cadences have a way of seeping into my own; I feel like I can better see the triangulation of beauty, tragedy, and humor around me, and I’m inspired to try to find its rhymes. It’s no different reading The Flame, the final collection of poems, notes, lyrics, and drawings the iconic Canadian writer finished just days before his death in 2016. Every day, I open to a new page and take in some verses, and there’s always a striking turn of phrase that stays with me for a while. Early on in “Blue Alert,” for example, comes “Your lip is cut on the edge of her pleated skirt.” Cohen’s self-portraits are a highlight, too, often framed by witty, insightful captions: One line drawing dated 2003 in which his face is particularly asymmetrical, his left eye halfway down his nose from his right, reads, “Just because we can’t see straight need not stop us from plunging forward.” The Flame is a reminder that Cohen’s art kept burning brightly until the very end, and it’s a gracious last invitation to warm ourselves by it. [Kelsey J. Waite]

Our Lady Of The Inferno by Preston Fassel

This month, I’m checking out the first book from the new imprint Fangoria Presents, Our Lady Of The Inferno by Preston Fassel. The book transfers the punchy midcentury pulp aesthetic to the equally grimy milieu of New York City in the early ’80s, for a serial-killer thriller that’s more character- and dialogue-driven than the majority of the dime-store novels that inspired it. The narrative stretches from a literal landfill—the appropriately named Fresh Kills Landfill in Staten Island—to the metaphorical landfill of Times Square, where our heroine, Ginny Kurva, an accomplished martial artist and den mother to the sex workers who live and work in the syringe-littered halls of the Motel Misanthrope, lives with her sister. Ginny, a hardened veteran of the sex trade in her early 20s, is a complicated character; she feels guilty about her complicity in her own oppression and that of the women she works with, and has appointed herself a sort of guardian angel of Times Square as a result. This puts her in direct confrontation with another, very different woman, Nicolette Aster, a manager at Fresh Kills who uses the landfill to dump the bodies that result from her occasional, inconvenient bouts of homicidal frenzy. Fassel structures the book like a slow-burn horror movie, opening with a scene of extreme violence, then backing up to give the reader time to get to know the main characters via long stretches of internal monologue. The balance between character-driven and genre-based can be a tricky one, and some of the dialogue struck me as excessively stylized, given the book’s otherwise naturalistic approach. But I liked Fassel’s impulse to flesh out (no pun intended) characters that are frequently reduced to stock stereotypes; even self-aware sociopath Nicolette is given more nuance than one might expect from a psycho killer, giving her inevitable climactic confrontation with Ginny an unexpected emotional resonance. [Katie Rife]