What great non-2018 book did you read this year?

As part of our year-end coverage, we’re once again asking this annual question of our staff and readership:

What’s the best non-2018 book you read this year?

Clayton Purdom

Except for the Beastie Boys Book, I didn’t read any books from 2018 in 2018, part of my lifelong inability to find contemporary fiction that I don’t immediately dislike. But I did spend a rapturous couple of weeks reading White Noise by Don DeLillo, which, published in 1985, is about as contemporary as I generally get, bookwise. In some ways, it feels like a product of its era, full of Reagan-era paranoia about consumerism, the failures of intellectualism, and television. I sort of knew all of this, from reputation, before I started it; what I did not know is that it’s also wildly, darkly hilarious, prefiguring the cosmic cuckoldry of A Serious Man and the droll despair of a Wes Anderson protagonist. It’s also really short, which is helpful if you read books at a snail’s pace, and full of marvelously crafted sentences, which is also helpful if you read books at a snail’s pace. It’s stuck with me like nothing else I’ve read in recent memory.

Nick Wanserski

After many years of friends suggesting with increasing exasperation that I check out some China Miéville, I finally picked up Perdido Street Station. The language is so dense and chewy that it took me a long time to finally consume the whole thing. But it was worth it. Few fantasy authors are as capable as Miéville at delivering nuanced and insightful character studies. By the loosest obligation to genre, Perdido would be considered steampunk—the city of New Crobuzon, where the story takes place, is a mottled clockwork of pneumatic tubing (bearing such neighborhood names as Smog Bend and St. Jabber’s Mound) and grotesque multi-species Dickensian social stratification. But Miéville is only interested in genre as a jumping-off point. His world-building is frighteningly elaborate and clever, but it’s only interesting to him inasmuch as how it can be used to explore the lives of the people inhabiting the place. Even the overarching story, of the human scientist Isaac and his kind of secret, kind of forbidden bug-headed artist girlfriend Lin, is just about two people trying to do their jobs.

Caitlin PenzeyMoog

The Orphan Master’s Son was so compelling and beautifully written that I couldn’t stop reading it, and its contents were so horrifying and brutal that I just wanted it to end. Adam Johnson’s tragic love story in modern-day North Korea is both an imaginative, spellbinding epic and one of the most depressing novels I’ve ever enjoyed. I’ve read about North Korea, of course, heard stories about how, seen from South Korea at night, its lights all go out when the government cuts the country’s power, plunging its cities into velvety blackness while Seoul’s lights blaze next door. But to read The Orphan Master’s Son is to live in North Korea for a while, and the absurdity that goes hand in hand with fascist governments is both blackly comic and deeply harrowing in Johnson’s telling, like 1984 meets Brazil meets Charles Dickens.

Laura Adamczyk

“The reason to have a home is to keep certain people in and everyone else out,” the protagonist of Dept. Of Speculation thinks while apartment-hunting in New York. Later a friend tells her, “The invention of the ship is also the invention of the shipwreck.” Then come the bed bugs. It’s a slow, creeping dread that drapes itself over the nameless wife of Jenny Offill’s second novel, a feeling that is at first indistinguishable from her usual state of disquiet. One of the things I liked best about this short novel is how un-novel-like it is, forgoing more familiar modes of characterization or plot development in favor of a perfect distillation of the most usual of stories: a man and a woman meet, fall in love, marry, have a child, and then start to grow apart. Reading it feels like stepping into a quiet room in a loud city—a library, a reading room, anywhere one feels compelled to whisper. For its delicate, precise compression, its perfect marriage of subject and form, it’s the kind of book where I can imagine the author, after having written it, never feeling the need to write another.

Danette Chavez

You know the expression, “Shop your closet”? Lately I’ve been browsing my own bookshelves in both an effort to clear the clutter and read more. If the Borders receipt in the inside flap is to be believed, I purchased Kevin Brockmeier’s The Brief History Of The Dead years ago and then promptly forgot about it. I finally tucked into it while traveling to and from Mexico last month, and I would like to thank my 2007 self, because in addition to an agreeably slow-burning mystery, Brockmeier offers the most resonant vision of the afterlife that I’ve ever read. Heaven isn’t a place on Earth, and hell doesn’t exist—but the belief that we live on in the memories of our loved ones and friends does. Those recollections and feelings carry over into a plane that’s like something out of the Forgotten Realms, but much more contemporary and with considerably more tedious responsibilities, including working to feed your undead self. I should have read this when I first plunked down the money for it, but the idea of working past our deaths works just as well in 2018, if not more so.

Kelsey J. Waite

I tend to read more poetry than anything, and probably less nonfiction than anything, but this winter I finally took on Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. Watching her lay out the history and inner workings of America’s racist criminal justice system was as moving a reading experience as I’ve ever had. Although it was published only eight years ago, Alexander’s argument that mass incarceration functions as a more formidable mutation of Jim Crow has thoroughly altered the way many people think of and talk about the system. Indeed, if you’ve seen Ava DuVernay’s The 13th, you’ve encountered some of Alexander’s ideas. But I highly recommend reading them from the author herself; she makes an unwieldy and difficult topic digestible and compulsively readable while sacrificing neither meticulousness nor emotion.

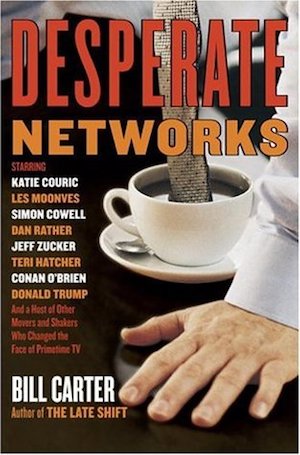

Alex McLevy

The stories of what goes on behind closed doors have an inherent voyeuristic appeal, whether it’s sexual, political, or—in the case of Desperate Networks, which I finally got around to this year—the frantic struggle for dominance and success among the four American television network as they moved from the ’90s into the 21st century. Bill Carter’s in-depth account of the dealings, developments, and cutthroat business strategies that took place among NBC, CBS, ABC, and Fox over roughly a 10-year period is engrossing stuff, especially when it comes to the tenuous role creativity plays in making a TV show a hit or a failure. With special attention to the profound transformation in news during this era and the idiosyncrasies of the talent behind the scenes at each of the networks, the book manages to make what’s happening off-camera far more absorbing than most of the shows Carter references. (Though the unlikely development process around Lost, for example, could constitute a juicy TV show in its own right.) It’s a gripping work of nonfiction, and essential reading for anyone interested in how the TV sausage gets made.