What non-2017 book did you finally read this year?

This week we begin our AVQ&As that serve as an overview of the year, starting with this annual question:

What non-2017 book did you finally get around to reading this year?

Kyle Ryan

I punched another hole in my “Chicago resident” card by finally reading Working by Studs Terkel. In it, the master oral historian talked to people all over the country about what they do for a living, across the spectrum of class and type of work (including, delightfully, actor Rip Torn). Terkel conducted the interviews in the early ’70s, but aside from there being a lot fewer manufacturing jobs these days, much of Working still feels relevant. Some moments show how times have changed more than others, like this salon owner: “Years ago, a wife wouldn’t think of going to a grocery store with blond hair. ’Cause what is she? A show girl? Light hair only went with strippers, prostitutes, and society women.” Then there’s fanatical football coach George Allen, who offended my A.V. Club sensibilities: “The achiever is the only individual who is truly alive. There can be no inner satisfaction in simply driving a fine car or eating in a fine restaurant or watching a good movie or television program. Those who think they’re enjoying themselves doing any of that are half-dead and don’t know it.”

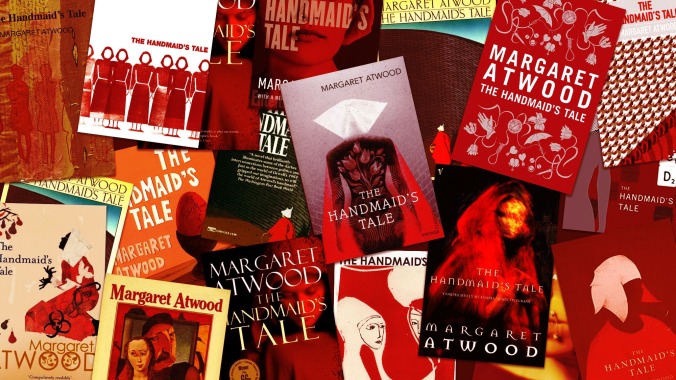

Laura Adamczyk

My friends have long recommended to me Margaret Atwood in general and The Handmaid’s Tale specifically, but I’m embarrassed to say, it took Hulu’s adaptation of her highly acclaimed 1985 novel to finally prompt me to read it this year. My reluctance was due to a general wariness of science fiction and fantasy, as, like authors relying on conventions in any genre, some speculative writers can depend too heavily on atmosphere and world-building for my taste. Perhaps in part because of this bias, The Handmaid’s Tale went well beyond my expectations. (I prefer the book to the television series.) It’s not just the religious tyranny of Gilead, a land in which women are treated as mere vessels for procreation, that is well rendered, but also the sentence-level prose. Atwood masterfully portrays the effects of living under a totalitarian regime in the narrator’s disquieting writing, an unsettling hush permeating the entire story. It’s not just what Offred says, but how she says it. In this repressive society that makes a show of valuing politesse, the brutal violence is all the louder when it comes. It’s an excellent, unsettling read.

Caitlin PenzeyMoog

My pick is 2014’s All The Light You Cannot See, so it’s not exactly that I finally got around to reading it so much as I got around to reading it a few short years after it published and won the Pulitzer Prize. I’ve been baffled by some of the other books that win that most prestigious of literary prizes, but I think All The Light You Cannot See earns it. Author Anthony Doerr crafts a dual war-time narrative that tells parallel stories of two children, a blind girl and a boy with a knack for electrical engineering; their stories stay separate for the majority of the book, though they’re aligned through, as the title suggests, light that’s not visible, either because of blindness or because it’s electrical. Doerr told The Guardian it took him 10 years to write the book, and it shows. An incredible amount of research must have gone into his European war-time settings, and the prose is nothing short of astonishing, every line like a piece of poetry.

Matt Gerardi

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a woefully poorly read person in general, but I’m especially unfamiliar with classic sci-fi. So over the summer, I grabbed an ancient paperback copy of The Martian Chronicles that I’d been eyeing for ages off my dad’s bookcase. I kind of figured it’d join the long list of books that I toss aside after reading a couple dozen pages, but it basically acted as my permanent beach companion. (Did I mention I’m also a woefully slow reader?) Even at 67 years old, I found it to still be be an effective combination of enchanting surrealism and sci-fi kitsch in a digestible anthologized package. It certainly helps that fun Twilight Zone-style twists and allegories for brutal colonialism never go out of style.

Laura M. Browning

This isn’t the first time this book has appeared in AVQ&A, but it’s so good that I don’t mind repeating it (and in fact, I’m pretty sure that’s how this book got on my to-read list in the first place). Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven follows the world as modern civilization effectively screeches to a halt, thanks to a swift and deadly strain of the flu. It takes a lot to transcend post-apocalyptic fiction these days, especially since it often feels like we’re in the midst of it already, but Mandel’s character-focused apocalypse moves between time and people, back and forth from history to future. That allows her to unravel the effects of the end of civilization—no TV, no internet, no planes, no infrastructure—slowly, just as one might slowly realize that yes, this is really happening. Maybe 2017 wasn’t the best time for me to read this book, and I highly recommend getting your flu shot before you start, but once you surrender to the terror in Station Eleven, there’s real human warmth in the collapse of civilization.

William Hughes

I was a truly awful reader this year, and the only two really great books I actually managed to finish, John Hodgman’s Vacationland and Angie Thomas’ New York Times bestseller The Hate U Give, both came out in 2017. I did catch up on a backlog of good comics, though, so I’m going to stump for Neil Gaiman’s Eternals limited series from back in 2006. Outside stuff like Sandman, I’m typically a Gaiman skeptic when it comes to comics writing, but Eternals is as enjoyable as its reputation suggests. Years of reading Alan Moore and Grant Morrison have made me a sucker for a story that digs up old, unused characters—especially those created by that wonderful gods-loving weirdo, Jack Kirby—and breathes new life into them, and Gaiman does a craftsman’s job of integrating these ancient divine beings into the modern world. (The lovely John Romita Jr. art didn’t hurt, either.)

Nick Wanserski

I don’t read a lot of mysteries. I lack the analytical mind that picks up on clues that allow me to unfurl the case alongside the protagonist. Hell, I barely have the attention to detail required to keep track of a half-dozen characters. But my wife strongly recommended The Cuckoo’s Calling, the first in a mystery series J.K. Rowling wrote under the nom de plume Robert Galbraith. And it’s enjoyable enough that I was able to stick with it, even as I was incapable of deciphering the novel’s central crime. This is due in large part to Galbraith/Rowling’s compelling central characters. The detective, Cormoran Strike, is a burly, thuggish-looking war vet with a prosthetic leg. But he’s thoughtful, reflective, and calmly competent in a manner that leans more toward empathy than the surly misanthropy that has defined so many unconventional protagonists recently. There’s also Robin, his assistant who’s discovering her enthusiasm and instinct for detective work is keeping her at a job that may never yield financial security. The human scale and lived-in familiarity with their day-to-day struggles keep the book grounded as they work to solve the murder of a larger-than-life model.

Erik Adams

This is really stretching the “get around to” part of the question, because nobody needs to get around to reading accounts of the television business that have been rendered obsolete by decades of cable expansion, media consolidation, and the release of the Big Three’s stranglehold over their medium. But I took The Sweeps: Behind The Scenes In Network TV out from the library as research for a 100 Episodes column, and wound up accruing a few weeks of late fees while paging through all the passages of Mark Christensen and Cameron Stauth’s book that don’t cover the development and debut of Night Court. It’s a flawed but engrossing read, with a number of needling New Journalism tics, a tabloid appetite for salaciousness, and a limited scope. (Depicting an era when American television was mostly CBS, ABC, and NBC, The Sweeps’ in-depth perspective is limited to the Peacock’s third of that equation.) Despite all of that, The Sweeps is an unknowing beneficiary of timing: In setting up their fly-on-the-wall operation ahead of NBC’s 1983-1984 season, Christensen and Stauth have a front-row seat to one of the most notorious swan dives in TV history, when the then-last-place network staked its comeback on infamous flops like Manimal and Mr. Smith—the latter a talking orangutan sitcom from half of the team responsible for Taxi. Also located in the authors’ excavation of the ratings basement: The cast and crew of a considerably more modest comedy from veterans of the Sunshine Cab Company, this one about the staff and patrons at a no-frills watering hole in Boston. While we watch Ted Danson pull the spectral strings of 2017’s best TV show, it’s fascinating to read the words of 1983’s Ted Danson, wondering what will become of then-struggling Cheers. For those time-capsule qualities alone, The Sweeps was well worth the $5.75 I still owe the Chicago Public Library.

Alex McLevy

I feel like an idiot that it took me this long to finally get around to Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. I have a small but insistent pile of old Russian masters on one of my bookshelves, the kind of novels you always want to start but then look at the page count and think, “Oof, that’s quite a commitment, maybe my next New Yorker is here already instead.” But after a bunch of waffling (to the point where I wasted the better part of a week making certain I had one of the better-reviewed translations instead of just reading the damn thing), I forced myself to open it, and after a slow start (that initial 50 pages takes some doing), it quickly blossomed into just as rich and rewarding a reading experience as I’d hoped it would be. It’s such a massive cast of characters, rife with the social mores and finely wrought customs of a different time, and yet the allegorical nature of the narrative still packs a wallop, a tale filled with stories inside stories, all curlicuing back upon themselves in ways that call attention to the myth-making power of narrative itself. I felt drained by the time I finished it, but it was a damn satisfying mountain to climb.