What’s your favorite horror subgenre?

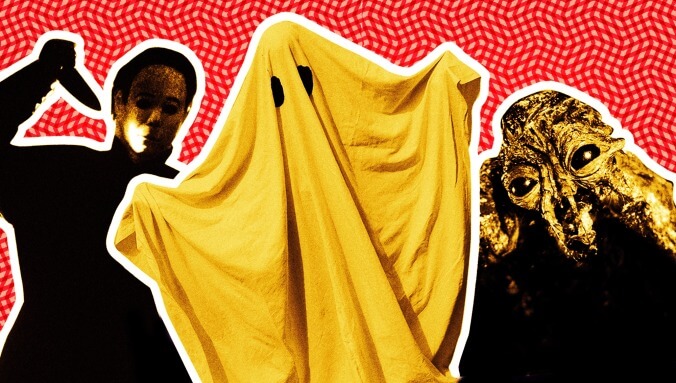

Photo: Slashers? (Compass International Pictures/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images), G-g-g-ghosts? (H. Armstrong Roberts/Retrofile/Getty Images), Or body horror? (SLM Production Group / Brooksfil/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images), Graphic: Karl Gustafson

What’s your favorite horror subgenre?

Join the discussion...