What’s your favorite piece of pre-20th-century pop culture?

This week’s question comes from reader XIO666:

“What’s your favorite piece of pre-20th century pop culture? I’ll go with Micromegas by Voltaire, a short novel where two intelligent beings from much larger planets visit Earth and are quite amused to find such miniature inhabitants believing the universe was made for them. One of these beings ultimately agrees to write a book for us Earthlings describing the meaning of life, however, it turns out that the book contains only blank pages. Micromegas is the precursor to all science fiction and one of the first serious examples of speculation on intelligent life elsewhere in the cosmos. It is also one of the earliest examples of what we would recognize as today as existentialist philosophy and also trolling.”

Gwen Ihnat

Every winter, at some point I return to the 800-plus pages of Anna Karenina. I even forced it on my book club, who protested its length, but I tried to win them over with the fact that it’s basically just a giant Russian soap opera. The title character’s famously doomed relationship with Vronsky becomes her undoing, but I love all the other relationships that swirl around her: Anna’s unfaithful brother Stiva, whose latest scandal opens the novel, or the tender love story of Levin and Kitty, who are like an inverse of Anna and Vronsky. It’s not a short undertaking, but it’s intoxicatingly easy to get sucked into Tolstoy’s gossipy format, which turns poetic at times, like when Levin is ruminating on his love for his land, or the train scenes that mirror each other by opening and closing the book. I’ve never even seen a movie version of it, because I love it so much I doubt any screen adaptation could live up to what I’ve crafted in my head. If you’ve never tackled Anna Karenina, I highly recommend it—maybe in January, curled up in your favorite chair with some vodka.

Danette Chavez

Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons are some of the best-known violin concertos, popping up on classical music stations all over the world and inspiring countless derivations (including the Diamond Music popularized by a series of De Beers commercials, which I once incorrectly assumed was actually Vivaldi’s work). More than any other work of classical music, they inspired me to pick up the violin. The Baroque arrangements made me aware of everything a violin—really, any string instrument—could do: mourn the loss of life in winter, exult in the spring, embrace the fall, and languidly enjoy the summer. I was never more than an adequate violinist, but when I played “L’inverno” for the first time in my high school orchestra, it very much felt like I had accomplished my dream.

Alex McLevy

From where I’m sitting at my desk, I can see more than a few of my favorite pre-20th-century texts sitting on my bookshelf: Plato’s Republic, Machiavelli’s Three Discourses, Rousseau’s Social Contract, Max Stirner’s The Ego And Its Own. (I swear I’m not being pretentious—eight years of a Ph.D in politics will do this to you.) Having spent a not-inconsiderable part of my adult life with my head buried in pre-Enlightenment-era writings, I used to be able to whip out a top-10 list of such works at a moment’s notice. I’m pretty sure it’s still lying around here somewhere, but it’s been a few years now since I was immersed in that world, and with the benefit of some time apart, I’ve had the opportunity to reflect on what truly moves me the most from before the 1900s, and truth be told, it’s not a book at all. It’s a painting: Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors. The image, at first glance, appears to be a classically renaissance artwork: The German-born artist knew his Dutch masters, and he surrounds his two ambassadors (one in secular clothing, the other clerical) with a plethora of symbols of humankind’s scientific advancements and erudition. Globes, a sundial, music instruments, textiles, and more line the walls and tables. But take a closer look—at first, there seems to be a strange line cutting across the floor between them. This is one of the most famous uses of anamorphosis in all of art history, a distorted perspective requiring the viewer to stand at just the right point of view to be able to see what’s been depicted. In this case, if you manage to look from high on the right side (or low on the left), you’ll see it: a human skull. Cutting across this work of art is a warped projection of death itself, erupting into normal reality to remind you that no matter the advancements of the species, death comes for us all. It gives me chills even now, and this was painted in 1533, for god’s sake. Holbein was a badass.

William Hughes

What’s that? A chance to talk about Johannes Trithemius, a.k.a. my favorite nerd in all of history? Don’t mind if I do! Born in 15th-century Germany, and raised by a stepfather who didn’t care for book learnin’, Trithemius had to do all his early reading on the quiet—which might explain why he became one of the founding fathers of modern cryptographic techniques. His most influential work was the three-volume Steganographia, my favorite book that I’ll never, ever read, and the text that lends its name to present-day steganography (i.e., hiding information within other text, or, as it’s now known, “designing escape-room puzzles”). Ostensibly a book of black magic about convincing spirits to convey secret messages for you, Steganographia is actually a textbook on early cryptography—something that only became clear when the cypher key to translate its first two volumes was published in 1606. (People are still working on the third.) Besides being serious business, vis-à-vis international politics and war, cryptography is also a deliriously dorky affair, and it’s clear that Trithemius must have been having an enormous amount of fun designing these incredibly obscure puzzles for his geeky descendants to one day decipher.

Katie Rife

The first motion-picture projector was invented in the late 1880s, and cinema’s first decade produced some fascinating experiments: the world’s first cat video, for example, or the first onscreen kiss. Both of those came through the workshop of Thomas Edison, however, and while Edison wasn’t really as bad as the Nikola Tesla fans of the world make him out to be, the Edison Co.’s willingness to electrocute animals to prove the superiority of its DC current is a big turnoff for me. So it’s a good and lucky thing that we have Alice Guy-Blaché, the world’s first female film director, to celebrate instead. Back when I was in film school, they were still teaching college kids that The Great Train Robbery (1903) was the world’s first narrative film. But in the decade-plus since, Guy-Blaché’s 1896 film La Fée Aux Choux has become rightly recognized as achieving that particular milestone a solid seven years before Edison cameraman Edwin S. Porter made his film. The plot of La Fée Aux Choux is simple: Based on a French fairy tale explaining where babies come from, a fairy pulls two real babies and one doll out of a cabbage patch. That’s about it, at least in the 1896 version. (Guy-Blaché remade the film with new footage in 1900 and 1902.) But for as simple as it is, this is one of the first films to have a plot based on a script, and not just document a real-world phenomenon. The fact that it was made by a visionary woman who’s recently been pulled from obscurity to take her rightful place in film history takes it from merely interesting to downright inspirational.

Erik Adams

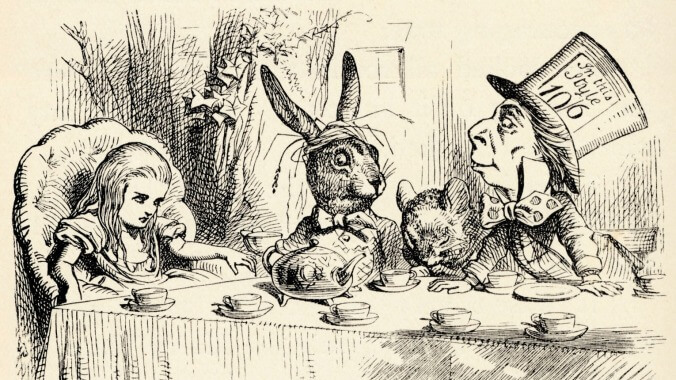

In the most “high-school drama kid browsing the T-shirt wall at Hot Topic” answer this side of “Edgar Allan Poe’s pretty cool,” I’m going to go with Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories. The dull, contemporary impulse is to plumb Alice’s adventures in Wonderland and through the looking glass for their most twisted elements (the same goes for L. Frank Baum’s Alice-inspired Oz novels)—a necessary reaction to their Disneyfication, but also one that narrows the range of the material’s imagination. Not to say that there’s nothing macabre about the tale of the walrus and the carpenter, or nothing sinister about a decapitation-happy monarch. But if that’s all you’re focusing on, you’re missing the ingenuity of Carroll’s language, or the boldly illogical manner in which his narratives proceed—that “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” conundrum that makes the books so ripe for adaptation, yet so easily garbled in their translation from page to screen. Better to get lost in the riddles and paradoxes and the vastness of this fantasy world, and the merest of visual hints provided by illustrations of a Mad Hatter who can’t move—let alone dance the Futterwacken.