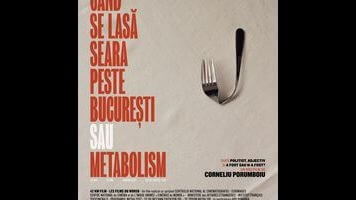

When Evening Falls On Bucharest, Or Metabolism is as unusual as its title

An early candidate for the year’s most willfully perverse film, When Evening Falls On Bucharest, Or Metabolism begins the alienation process with that title, which rivals Birdman Or (The Unexpected Virtue Of Ignorance) for pretension. (The needless parenthetical, which The A.V. Club has chosen to ignore, puts Birdman over the top.) Thankfully, though, Romanian filmmaker Corneliu Porumboiu has a wry sense of humor, which prevents this oddball meta-exercise from seeming overly academic. Its alternate title, Metabolism, even has a literal reference within the narrative: One of the characters suffers—or claims to suffer, anyway—from an ulcer, and there’s a lengthy scene toward the end of the film in which he shows skeptics a video of an endoscopy he’s allegedly had performed. Porumboiu probably felt that a colonoscopy would be a bit too on the nose (so to speak), but he still succeeds in having some fun with the way that his movie deliberately travels up its own ass.

Yes, this is a film that’s explicitly about filmmaking, made by the guy who concluded his previous feature, Police, Adjective, with a bravura recitation of multiple dictionary definitions. The extremely minimal plot involves the efforts of director Paul (Bogdan Dumitrache) to persuade his lead actress, Alina (Diana Avramut), to perform a nude scene. This protracted negotiation is complicated by the fact that Paul and Alina are romantically involved, and further complicated by clear indications that they’re not likely to be romantically involved for very much longer. Meanwhile, Paul is doing his best to ignore the entreaties of his producer, Magda (Mihaela Sirbu), who’s convinced—not without reason, it appears—that Paul’s constant delays and revisions are motivated not by creative difficulties nor by gastric health issues (hence the endoscopy video), but merely by his penchant for dicking around, both figuratively and literally.

That synopsis may seem fairly straightforward, but only because it omits several long conversations that place the movie’s ostensible subtext front and center. Throughout, Porumboiu playfully withholds virtually everything of potential narrative or prurient interest. We never get any real sense of what the movie Paul is making is about, for example (much less see any of it being shot); when Paul and Alina have sex, a half-closed door obstructs the camera’s view. Even the arguments about the nude scene are relatively brief. Instead, there’s endless explicit dialogue about the nature of form and function, as Paul pontificates about the way that film magazines in the pre-digital age dictated a movie’s rhythm, or the way that Chinese cuisine was shaped by the country’s use of chopsticks rather than forks. Naturally, this can’t help but call attention to the unusual form (and intentionally dubious function) of Bucharest/Metabolism itself, which was shot on 35 mm and is constructed of only 18 oft-maddening shots. At times, Porumboiu’s mix of repetition and resignation recalls Samuel Beckett, and if the overall result is more of a clever exercise than a proper movie, it’ll still have some dryly amusing appeal for those who appreciate intellectual absurdism.