When Michael moonwalked: Motown 25 said hi and goodbye to two generations

Michael Jackson moonwalked in public for the first time on March 25, 1983, in the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, with showbiz bigwigs in the balcony and an audience of dedicated Motown fans filling the orchestra seats. The rest of the country would get the chance to see Jackson scoot backward nearly two months later, on May 16, 1983, when NBC aired the two-hour special Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever. In the weeks between, director Don Mischer and producer Suzanne De Passe would deal with Jackson and his lawyers looking over their shoulder, making sure they edited his performance of “Billie Jean” to Mr. Jackson’s specifications; they’d also deal with NBC executives suggesting that they record testimonials from famous Motown fans like Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney, so the show wouldn’t be “too black.”

Mischer and De Passe stuck to their guns with NBC, but let Jackson more or less have his way, and when the ratings came back, they were rewarded with “the best demographics of any special in NBC history,” according to Mischer on Time-Life and Starvista’s new Motown 25 DVD set. The day after the show aired, Mischer was at The White House to supervise a Barbara Walters special about the Reagans, and he says that even people who had no idea he directed Motown 25 were walking up to him and saying, “Did you see Michael Jackson on TV last night?”

The Michael Jackson moonwalk is the moment everyone remembers best from Motown 25, but the whole special occupies an odd place in pop culture history, in ways that even the hours of bonus features on the Time-Life/Starvista set don’t really acknowledge. The special gave Jackson a cultural boost that he may or may not have needed—depending on who’s recounting the Legend Of The Moonwalk—but it undeniably revived interest in the Motown back catalog, which would become as much a part of the soundtrack of the 1980s as it was in 1960s. The real question is whether Motown 25 changed the label from an active part of modern music into an archive for Hollywood producers and advertisers to raid for cheap nostalgia.

As for how Motown 25 itself comes across today, it’s a curious mix of frank history and variety-show goofiness, liberally sprinkled with electrifying reunions. In the DVD featurettes, De Passe recalls the layers of agents, managers, lawyers, and bookers Motown Productions had to fight through to get the talent to agree to appear, and actually watching the special now feels similarly sluggish. Make it through a disappointingly lifeless performance by host Richard Pryor (reduced to reading someone else’s dumb jokes off a teleprompter), sidestep the corny Lester Wilson Dancers numbers (which look like outtakes from some old Sonny & Cher or Donny & Marie show), and listen past the over-orchestrated, thumpless musical backing (sorely lacking the presence of Motown’s “Funk Brothers,” who weren’t invited to the party), and the reward is a modest collection of moments like the charming “battle of the bands” between The Four Tops and about half of the original Temptations.

There are a few Motown 25 highlights besides Michael Jackson’s moonwalk. Mischer says that Stevie Wonder almost didn’t show up because his assistants didn’t realize the taping was a one-night-only event, yet both Wonder and a pre-taped Lionel Richie—two old-guard Motown hitmakers who were still with the label and still thriving on the pop charts—have two of the special’s most touching moments: Richie singing a tender ballad to a 6-year-old girl with sickle-cell anemia and Wonder’s voice cracking as he thanks Motown and the fans for giving a poor, blind, black kid an unlikely career.

But the badass of all badasses in Motown 25 is Marvin Gaye, then in the middle of a late-career comeback with the hit “Sexual Healing” (recorded for another label), and just a couple of months removed from an emotional appearance at the NBA All-Star Game, where he sang a Gaye-ified version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Gaye would be a dead a year later, murdered by his father. Here, though, he comes across as vital, and even a little dangerous, as he sits at the piano and recites a speech about the decades of struggle black artists experienced before Motown, and then rises to sing “What’s Going On.” Gaye looks like he’s ready at any moment to stalk off the stage, and that tension makes it all the sweeter when he coos his way through his best-known song.

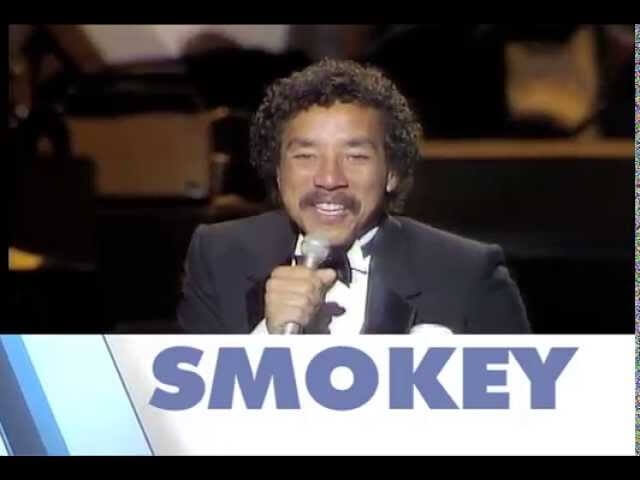

DeBarge and High Inergy, trotted out to represent Motown’s new breed, don’t fare nearly as well, coming across exactly like the here-today/gone-tomorrow pop readymades that they’d turn out to be. And Motown 25’s slate of special guest stars runs the gamut from smart (Howard Hesseman and Tim Reid reprising their DJ characters from WKRP In Cincinnati) to oh-so-1980s (motor-mouthed commercial pitchman John Moschitta). Linda Ronstadt sings beautifully in a duet with Smokey Robinson. And José Feliciano? You got no complaints. But when Adam Ant leaps across the stage like a time-traveling renaissance court jester, gulping his way through a jaw-droppingly awful rendition of “Where Did Our Love Go,” not even an unplanned cameo by a strutting, sexy Diana Ross can salvage the segment.

Yet even the worst of Motown 25 provides the proper context for Michael Jackson, who stuns the crowd about halfway through the show.

Here are some key facts to keep in mind about Jackson’s Motown 25 performance:

- Though Motown 25 is often credited with turning Jackson into a phenomenon, when Jackson recorded the show “Billie Jean” was already the No. 1 song in the country (his second consecutive Billboard Hot 100 chart-topper from Thriller, following the Paul McCartney duet “The Girl Is Mine”); “Beat It” was No. 1 by the time the special aired; and Thriller itself had been the Billboard No. 1 album for several weeks before the taping (supplanting Men At Work’s Business As Usual, which topped the charts for the first eight weeks of 1983). The album retained the top spot throughout the weeks of editing, and it was still No. 1 both when Motown 25 aired and for about two months following. It would continue to be the No. 1 album off and on all year, replaced periodically by the Flashdance soundtrack, The Police’s Synchronicity, Quiet Riot’s Metal Health, and Lionel Richie’s Can’t Slow Down. (All told, only six albums reached Billboard’s No. 1 spot in 1983.)

- Jackson’s appearance on Motown 25 doesn’t begin and end with “Billie Jean.” He first comes out onstage alongside his brothers, doing some of their old moves during a medley. The crowd flips the hell out for the whole Jackson 5 segment—especially when Jermaine’s microphone goes dead during “I’ll Be There” and Michael illustrates the meaning of the song by grabbing his brother’s hand and sharing his own mic. The audience then goes from excited to absolutely bonkers when the brothers leave the stage and the familiar opening beats of “Billie Jean” begin.

- Jackson lip-synchs “Billie Jean,” and not well. The close-ups on his face during the song almost break the spell of his performance, because his mouth movements are so out-of-step with the lyrics.

- Jackson moonwalks twice during “Billie Jean.” Each time, the move barely lasts one second.

As someone who watched Motown 25 when it originally aired, I can attest that the “Billie Jean” performance—and the two combined seconds of moonwalking—was a true “Did I just see what I thought I saw?” monocultural moment. The kids at school were talking about it the next day. My dad—who favored bluegrass and jazz fusion over pop and R&B—gushed over it. For all of NBC’s fears that Motown 25 wouldn’t connect with a wide enough (or white enough) audience, it became something that nearly everybody was talking about that summer.

The aftereffects of Motown 25 followed very different paths, though. NBC, apparently now convinced that “a black show” could cross over, greenlit The Cosby Show for the fall of 1984. Older Motown acts like The Temptations and The Four Tops started touring again on the nostalgia circuit, while the label released a slew of budget-priced “25th Anniversary” compilations on cassette and the new medium of compact disc, raking in enough money to cover the production costs of Motown 25 several times over. On September 28, 1983, the movie The Big Chill opened, using a Motown-heavy soundtrack to counteract the melancholy in its story of disillusioned ex-hippies. In 1986, the California Raisin Advisory Board and animator Will Vinton put the Motown classic “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” in a wildly popular commercial. In 1988, the TV series Murphy Brown and China Beach both debuted, leaning heavily on Motown songs as soulful signifiers. After Motown 25 won an Emmy and a Peabody, De Passe followed it up with a 1985 NBC special called Motown Returns To The Apollo, and then 1986’s The Motown Revue miniseries, also for NBC. The 1980s itself became something of a living museum of Motown.

Meanwhile, over time, the Michael Jackson moonwalk moment became more divorced from its original context—just as Jackson himself seemed much bigger and more relevant than anyone he shared the stage with in Pasadena that night in March 1983. There was a different energy to Jackson’s performance than to anything else in Motown 25. Even the great Gaye and Wonder received only spirited applause, mostly from the older fans and fat-cats in the crowd. With Jackson, though, it was like a switch had turned on, both within him and within the younger members of the audience, who’d grown up with Jackson. In the years that followed, Jackson would continue to thrill the youth, and would break down racial barriers on the pop charts and on MTV that resembled what other Motown artists had faced in the 1960s. He’d also lose some of the older viewers who loved him on Motown 25, but started to see him more as a weirdo than as the reincarnation of Fred Astaire. (My dad dropped Jackson’s name somewhat contemptuously in the only dirty joke I can ever recall him telling me: “Why does Michael Jackson wear one glove? So he won’t beat it.”)

People sometimes forget that after Jackson departs in Motown 25, there’s still about an hour of show left—much like people forget that when the United States Olympic hockey team beat the Soviet Union, they had to play one more game to claim the gold medal. And there’s still one more magical moment remaining in Motown 25, when Diana Ross closes the show with a very brief Supremes reunion (lasting less than a minute), then invites all the performers back to salute Motown founder Berry Gordy. On the DVD set, De Passe chokes up remembering the Motown elite embracing her boss, who’d been through some tough times, and had strained relationships with nearly everyone on that stage. It’s a tear-jerking finish, undeniably.

Motown 25 does a good job of contextualizing the label’s cultural impact via archival clips from TV shows like The Ed Sullivan Show and To Tell The Truth; and via a pointed Dick Clark reminiscence about the how the white and black music worlds interacted, pre-Motown. But Motown’s behind-the-scenes squabbles go undocumented, so only longtime fans would’ve gotten the significance of Ross sharing a song with the group she abandoned, or Robinson reuniting with The Miracles. Reportedly, all of the estranged old-timers were happy to see each other again, and stuck around to watch each other’s rehearsals—somewhat in the spirit of competition, just like the old days.

When they all surround Gordy at the end of Motown 25, this generation of men and women who changed popular culture and race relations, there’s a mix of genuine gratitude and showbiz schmaltz in play. It’s a necessary moment—a catharsis effected by the demands of television. But it’s also a kind of goodbye. Goodbye to Gaye, with only a year to live. Goodbye to Pryor, whose heyday was already behind him. Goodbye to the ongoing viability of Robinson and Ross, he in his early 40s and she in her late 30s, and both about to record their last big hits over the next few years. These people are legends, all of them. And yet it’s hard not to look past them on the stage, keeping an eye out for a man in a glittery coat, always asking, “So what’s Michael doing?”