Viewers losing patience with the meditative pace of Twin Peaks’ revival should find some relief in the jackrabbit-fast pace of “The Return, Part 14.” In just one hour, Albert briefs Tammy (and us) on the very first Blue Rose case, Diane reveals her family connection to the search for Dale Cooper, Sheriff Truman and his chief deputies find more than they bargained for when they hike up to Jackrabbit’s Palace, Andy visits the black-and-white world of The Fireman, and James hears his young co-worker’s tale of finding his destiny in a green gardening glove (and in Twin Peaks). Oh, and Sarah Palmer bites a man’s throat out.

It sounds like a lot of action, and it feels like a lot of action. But despite a few moments of intense excitement, much of “Part 14” is just people sitting around, telling stories. In the first few minutes, Albert recounts the details of Lois Duffy’s apparent murder in 1975, and also of Lois Duffy being charged with that murder. (“By the way,” he adds drily, “Lois Duffy did not have a twin sister.”) That case led Gordon Cole and Phillip Jeffries to develop an interest in a specific kind of case, the kind that‘s not susceptible to traditional investigatory techniques.

Albert’s message isn’t just the origin of the Blue Rose cases. He wants to see if Tammy, new to the task force, can spot the crucial line in his story. When he asks, “Now, what’s the one question you should ask me?” Tammy knows the answer. The crux of the Lois Duffy case lies in the victim’s last words: “I’m like the blue rose,” the seeming doppelgänger said in the seconds before she died and then vanished. Like a blue rose, the vanished version of Lois Duffy is unnatural, something conjured up from somewhere else. “A tulpa,” Tammy concludes, to Albert’s approval.

When Diane joins them, Albert briefs her on the significance of Maj. Briggs’ body, found out of place and out of time, and the wedding ring complete with an inscription (to Dougie Jones from Janey-E) recovered from his stomach. Then Diane tells a story of her own: Her estranged half-sister is named Janey, nicknamed Janey-E, and married to a man named Douglas. Is Janey (Evans?) really Diane Evans’ half-sister? She’d be a fool to tell a lie so easy to check, but those under the sway of Bob and his ilk have done more foolish, more reckless things. And this information will lead the team to Las Vegas, where Dark Coop wants them.

Then it’s Gordon Cole’s turn to tell a story, the story of last night’s dream, which becomes the story of Cooper’s dream, which becomes the story of the last sighting of Phillip Jeffries (David Bowie). Like Lois Duffy, Jeffries was both there and not there. In Gordon’s dream, and in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Jeffries appears in the FBI’s Philadelphia office, points dramatically at the young Dale Cooper, and asks Gordon, “Who do you think that is there?”

This scene plays out just as it does in Fire Walk With Me (I recommend FWWM; it’s the legend that can help you map out this season of Twin Peaks), but in “Part 14,” Gordon is surprised by the memory. “Damn!” he explodes as he finishes his story, “I hadn’t remembered that! Now this is really something interesting to think about.” An obscure understanding dawns on Albert’s face as he chimes in that he, too, is starting to remember this.

“The Return, Part 14” is built on a paradox. These stories are tense, thrilling, touching, and thoroughly believable. They’re also intentionally flimsy, riddled with reasons to doubt them. No story is entirely true to the original experience, for too many reasons to count. Memories are faulty. Moments are evanescent. Narrators are unreliable. Even the most faithful retelling necessarily leaves out great swathes of information, if only because a story that recounted every bit of its circumstances would be a cacophony of detail with no intelligible meaning.

Just think of Lucy once again telling her sheriff which line he should answer on his phone—just as she did in her first appearance, relaying a call to Harry Truman—and you immediately see how too much detail muddies the message instead of making it clearer. Or witness Gordon Cole, whose powerful hearing aid allows him to hear the vital conversation, but also makes every day sounds like the window washer’s squeegee into an agony of information overload.

This scene is full of nods to the challenges of combining the effective transmission of information with the subtler, more ambiguous aspects of effective storytelling. Even the staging of the FBI’s many portable instruments arrayed around the room nods to it. To accommodate all their equipment, they’ve had to pull down some framed paintings, which sit propped against the wall. There’s often a tension between artistry and exposition, and sometimes one has to be sacrificed to make room for the other.

Stories get bigger or smaller depending on who’s telling them, and when, and why, and to whom. Freddie (Jake Wardle), who works alongside James as a Great Northern security guard, is reluctant to tell his story precisely because it’s so unbelievable, but James turns that implausibility into a reason to share it. After all, if no one will believe you, what’s the harm in telling an incredible story?

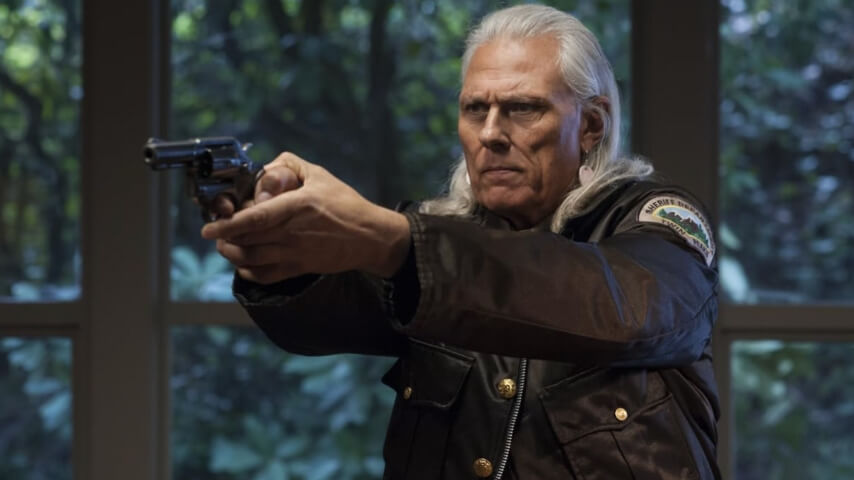

Leading Frank Truman, Hawk, and Andy deep into the woods to the place he and his father named Jackrabbit’s Palace, Bobby remembers that his father would walk him there, to the massive splintered tree stump not far from his top-secret station, and “we’d sit here and make up great tall tales.” The policemen can only hope this elaborate outing isn’t another of Garland Briggs’ tall tales. Their faith is rewarded when they find Naido (Nae Yuuki), the eyeless woman who piloted a vessel through a starry void, lying in the forest.

When Andy is swept away from the woods into The Fireman’s black-and-white universe, he’s told a story, too, though The Fireman’s story is delivered in a series of images. (I admire how deftly the blocking and editing promised it would be Andy, from the moment he’s shown lagging behind as the four men climb a mossy hill.) He returns with an understanding—an understanding that Harry Goaz conveys through Andy’s stance, his confidence, and his unaccustomed directness—greater than words could convey. While his colleagues are still milling around confused, Andy crisply informs them how to protect Naido, and where and why. He cradles her gently but firmly as he bears her down the hill. His last instruction reflects the importance, and the danger, of sharing stories. “Don’t tell anybody about this.”

Sarah Palmer only tells one incredible story—one big lie—in “Part 14.” But she doesn’t seem to care if anyone believes her. When a fellow barfly at Elk’s Point #9 approaches her, she tries to warn him off, punctuating her curt replies with a heartfelt “please.” But he won’t listen, even when she tells him with chilling steadiness, “I’ll eat you.” It isn’t until she pulls off her face, revealing a void in which float a black-and-white hand and a grinning black-and-white mouth, that her harasser realizes he’s made a terrible mistake.

Faster than the camera can capture, Sarah—who was reintroduced sitting in the dark of her former family home, watching predators tear apart their prey—lunges out and snatches a bite from his neck. Screaming in false shock, she tells the bartender the victim “just fell over,” but when he warns her the police will figure out what happened, she deadpans, “Yeah. Sure is a mystery, huh.”

Knowing who is telling a story and why is crucial to understanding it. But even as it spins its spell of stories, Twin Peaks destabilizes the nature of storytelling. In this third season, the show is spelling out more than I ever expected to hear, but refusing to offer any certainty about whose story this is, or why it’s being told. As Monica Bellucci (playing herself) tells Gordon in his dream, “We’re like the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream. But who is the dreamer?”

Stray observations

- • I’m suspicious of Tina’s daughter’s friend, who sits across from her at the roadhouse and draws out her story about the last time she saw Billy. (The character, played by Emily Stofle—who is married to David Lynch—is identified in the credits as Sophie, but neither woman is named in their conversation.) Nothing she says is overtly out of line, but her persistence, her avidity as her friend describes Billy’s blood “gushing like a waterfall,” and the last sly look she shoots her companion all add up to something wrong.

- • James, patrolling the dark cellar corridors of the Great Northern, seems to have found the point of origin for that ringing Ben and Beverly were trying to track down.

- • Whatever story it is that Naido is telling in moans and chirps, that story is doubtless incomplete, too, no matter how fascinating it is.