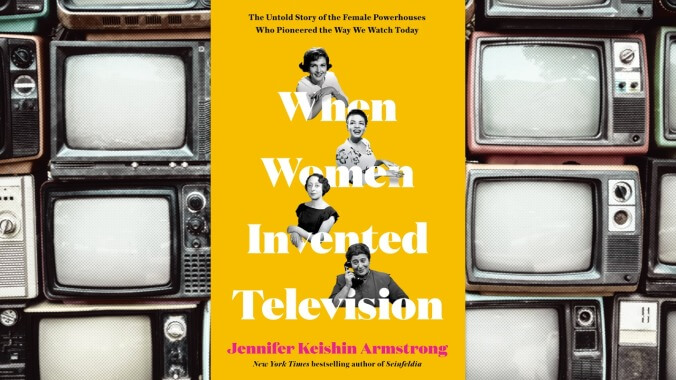

Cover image: Harper Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Pop culture historian Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s last few books have been about fairly recent, extraordinarily popular TV phenomena: 2016’s Seinfeldia and 2018’s Sex And The City And Us. In her new volume, When Women Invented Television: The Untold Story Of The Female Powerhouses Who Pioneered The Way We Watch Today, Armstrong uses her impressive analytic and research skills to unearth some much less-explored ground. Women Invented Television focuses on four women in particular—Gertrude Berg, Irna Phillips, Hazel Scott, and Betty White—who all, in individual ways, helped create the TV landscape still expanding today.

Granted, there’s at least one name on that short list you’ll probably recognize: Betty White, who most know as the star of The Mary Tyler Moore Show and The Golden Girls. Many may not realize, however, that White was one of the very first luminaries of the medium, in the early days when the cultural focus was switching from radio to television. New stations desperate to jump onto TV but still figuring out the parameters and logistics had hours of (live) airtime to fill. A natural in front of the camera, White wound up co-hosting a daily five-hour talk show out of California, eventually starring in one of the very first sitcoms, Life With Elizabeth. The Wild West atmosphere of TV’s earliest days actually made it easier for some women to make important inroads: When Women Invented Television begins with Berg storming CBS head William S. Paley’s office, demanding that her popular radio show, The Goldbergs—which she created, wrote, and starred in—be brought to air, even though the Jewish-themed program was a riskier proposition for Paley than the populist variety shows of the era. Based in Chicago for most of her career, Phillips created several soap operas for radio, and also campaigned furiously to have Guiding Light make the jump from wireless to TV; she eventually succeeded, and the show lasted 57 years, until 2009, making it the longest-running program in the history of television.

But Berg’s, Phillips’, and White’s stories are fairly familiar, in some fashion or another. When Women Invented Television’s biggest revelation is Hazel Scott, a singer and piano prodigy, whose signature was playing two different pianos with two different hands. She became the first Black performer to host a national evening variety program, The Hazel Scott Show. Scott, married to U.S. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell at the time (the first African American to be elected from New York to Congress), spent her life protesting segregation and discrimination: suing a restaurant that refused to serve her, for example, in a landmark case.

Scott’s story is so gripping, in fact, that sometimes it’s disappointing when the narrative switches to one of the other leads. The shifts between the four different biographies can be jarring, though helpful at times. Armstrong never comes right out and analyzes the differences in the rises and falls of these women, but it’s quite clear that White had an easier path to success than Scott or Berg did. Those disparities become even more plain in the book’s most gripping section, as both Berg and Scott become ensnared in the Hollywood blacklist during the era of McCarthyism. Berg received a ton of pressure from her sponsor, General Foods, to fire the blacklisted Philip Loeb, who had played her husband on The Goldbergs for several years. Scott volunteered to appear in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee in a futile attempt to clear her own blacklisted name, and she eventually left the country altogether. When Nat King Cole got his own variety show years later, he proudly (but incorrectly) proclaimed he was the first Black person to do so, the once-popular Hazel Scott Show becoming a lost footnote in TV history.

Which is just one reason why Armstrong’s book is so valuable. One might assume that a book about female pioneers in television would have Lucille Ball front and center. She does appear, but her more familiar tale takes a back seat here to these lesser-known stories, which are bolstered by Armstrong’s interviews with Scott’s son and Berg’s grandchildren, and White’s memoirs and other archives. Armstrong also makes strong statements about the fact that women were marking these accomplishments during a time when they were expected to stay home and care for their families. Of the four, only Berg had a traditional home of a husband and children, the inspiration for the family she depicted onscreen. White was a divorcée and was billed as a single success, but as her fame grew, the most common question she received was when was she going to get married. Armstrong writes that White, who was busy establishing her own production company, “was more interested in playing a housewife on television than in being one in real life.”

These four women prioritized career over family, bravely carving out the professional lives that they wanted, even as they faced a Sisyphean climb to do so. Mostly, states Armstrong—just like today’s female showrunners like Shonda Rhimes and Amy Sherman-Palladino—they were battling the patriarchy, which they did by insisting on their own terms for their creations, or by hiring female writers and directors themselves. “It’s time we remembered Betty White as more than the sassy old lady who’s still got it—she was also one of television’s first female producers and a foundational contributor to the medium who fought patriarchal expectations at every turn,” Armstrong writes. “[I]t’s time we also remember White’s sisters who, along with her built the medium that now dominates our lives.” Armstrong’s volume is a definite step in the right direction toward giving just some of these forgotten women their due.

Author photo: A. Jesse Jiryu Davis

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)