Where to start with the deep sound of roots reggae

Pop culture can be as forbidding as it is inviting, particularly in areas that invite geeky obsession: The more devotion a genre, series, or subculture inspires, the easier it is for the uninitiated to feel like they’re on the outside looking in. But geeks aren’t born; they’re made. And sometimes it only takes the right starting point to bring newbies into various intimidatingly vast obsessions. Gateways To Geekery is our regular attempt to help those who want to be enthralled, but aren’t sure where to start. Want advice? Suggest future Gateways To Geekery topics by emailing [email protected].

Geek obsession: Roots reggae

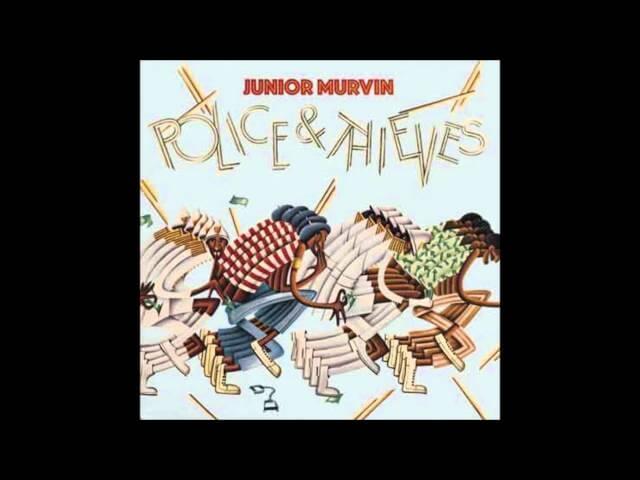

Why it’s daunting: With the death of Junior Murvin in December, reggae lost one of its most influential voices. But the subgenre of roots reggae also lost a prime mover. After coming into existence in the early ’70s, roots reggae rode a rising tide of political and spiritual consciousness—particularly in regard to the Rastafarian faith—that ran counter to the more romantic air of its immediate predecessor, rocksteady. Roots reggae dug deeper, both thematically and sonically, directly addressing poverty, brutality, and Rasta culture with a sparser, darker sound that evolved parallel to dub—to the point where the two became inseparably intertwined. But roots reggae, in spite of its experimentation with the concept of studio-as-instrument, remained primarily a singer-songwriter’s domain. And while Bob Marley became roots’ most visible and bankable icon by far, his legend and fame continues to overshadow multitudes of worthy artists like Murvin—who together not only influenced everyone from Eric Clapton to The Clash to Jay Z, but also unleashed a flood of recordings that have attained the status of classics. If any one subgenre of reggae spawned the stereotypical complaint that “it all sounds the same,” it’s roots. But once that gross misconception is swept away, a broad and consistently underappreciated spectrum of roots emerges, from the aching and ethereal to the brooding and revolutionary.

Possible gateway: Various Artists, Rockers soundtrack

Why: Dozens of roots reggae anthologies have been compiled since the subgenre’s ’70s heyday, but none can compete with the soundtrack to Rockers. The film (and accompanying album) came out in 1979, and it encapsulates roots just as it was about to give way to the more upbeat sound of ’80s dancehall. Taken together, the songs and artists featured on the record provide just as vivid a snapshot of Jamaican culture as does the film. Along with fierce tracks from Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer—both solo artists after spending formative years harmonizing with Marley in The Wailers—are songs from rising stars like Jacob Miller (both solo and with the band he fronted, Inner Circle) and Gregory Isaacs. But towering figures such as Murvin and Burning Spear and also appear, in addition to the rocksteady-turned-roots outfit The Heptones, which lends a righteous gravitas to the album that’s only grown over the decades. Murvin’s contribution, “Police And Thieves,” became known to a wider audience after being covered by The Clash—but there’s no beating the keening, hymnal, Curtis Mayfield-esque power of the original.

Next steps: Even if “Chase The Devil” were the only song Max Romeo had ever recorded, he would have been recorded in the annals of roots as a singer of prophetic resonance. Luckily, he released much more than that—and the album “Chase The Devil” appears on, 1976’s War Ina Babylon, stands as one of roots’ major works. Produced by Lee “Scratch” Perry at his studio Black Ark, War Ina Babylon is part of what would become known as his “holy trinity” of albums (the others being Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves and The Heptones’ Party Time)—a hat trick that cemented Perry’s stature as a roots architect (that is, when he wasn’t being a roots astronaut). But it’s Romeo’s supple yet authoritative vocals (as well as the superb backing by Black Ark’s house band, The Upsetters) that turn Perry’s atmospheric, effects-laden production and make War Ina Babylon far more than the sum of its rhythm and voice.