Where to start with Thelonious Monk

Pop culture can be as forbidding as it is inviting, particularly in areas that invite geeky obsession: The more devotion a genre, series, or subculture inspires, the easier it is for the uninitiated to feel like they’re on the outside looking in. But geeks aren’t born; they’re made. And sometimes it only takes the right starting point to bring newbies into various intimidatingly vast obsessions. Gateways To Geekery is our regular attempt to help those who want to be enthralled, but aren’t sure where to start. Want advice? Suggest future Gateways To Geekery topics by emailing [email protected].

Geek obsession: Thelonious Monk

Why it’s daunting: The brilliant but troubled bebop pioneer and jazz pianist-composer Thelonious Monk has never been easy to understand. His body of work stretches from his first recordings as a leader for Blue Note Records from 1947 to 1952 (originally issued on 78s and later collected on a pair of LPs), to a trio of records for upstart label Prestige in the early ’50s, to his most fully realized later periods, in which he recorded for Riverside (1955-61) and Columbia (1962-68).

Why does Monk still seem impenetrable even today? His angular compositions and odd habits have left jazz critics and listeners befuddled over the years. Luckily, Robin D.G. Kelley’s 2010 biography, Thelonious Monk: The Life And Times Of An American Original, is helping to shift the conversation from his eccentricity to his intellect. Kelley, compares Monk’s role in the formation of bebop to the mercurial New Orleans jazz musician Buddy Bolden’s similar role in developing the first strains of jazz. They were both, Kelley writes, “that missing link who started it all, but then disappeared.”

And, like Bolden, who was committed to an insane asylum in 1907, Monk had mental-health issues. In Clint Eastwood’s 1988 documentary, Thelonious Monk: Straight No Chaser, Monk’s son, T.S. Monk, manager Harry Colomby, and late-period collaborator Charlie Rouse all testify to his schizophrenic episodes and manic depression. By the 1970s, as jazz-fusion was becoming the order of the day, Monk gave up music and went into seclusion, further complicating his legacy.

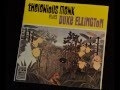

Possible gateway: Thelonious Monk Plays Duke Ellington

Why: Monk grew up in New York, studied music theory, and fell under the sway of stride pianists like Art Tatum and James P. Johnson. It was Monk’s brilliant stride-influenced left-hand rhythms that first attracted Blue Note’s Lorraine Gordon at the bedroom audition Monk gave the jazz label in 1947. For Monk newcomers, the best place to start is his first album for Riverside in 1955, where he does beautifully minimal readings of Duke Ellington tunes with a trio. Drummer Kenny Clarke, who worked with Monk in the Minton’s Playhouse house band that helped give birth to bebop, and bassist Oscar Pettiford lay the perfect understated groove for Monk to stretch out over. Monk gives “Solitude,” the 1934 Ellington composition that Billie Holiday (whose picture Monk taped to his ceiling) sang on her 1952 self-tiled debut LP, a sublime reading. For “Sophisticated Lady,” he pays homage to Ellington’s suaveness. Here, Monk is smooth, nimble, and airy. For a guy once called “the elephant on the keyboard,” it’s a notably different approach. These relaxed tempos are Monk at his best.

Next steps: After delving into Monk at his most accessible, there are two directions to take, each a wormhole to deeper Monkisms. By the ’60s, Monk had moved to Columbia Records, scoring a hit with Monk’s Dream in 1962. Solo Monk, from the following year, shows the pianist in solo flight gear on the album cover. The album picks up on the Ellington record, using silence and space to great effect. Opener “Dinah” is jaunty, carefree, and fun.

The second path leads to Monk’s work with John Coltrane, who joined the pianist’s quartet in 1957 and performed and recorded with him for seven months. Though not released until December 1961 (about a year after Coltrane’s own Giant Steps was released), Thelonious Monk With John Coltrane is a heavy meeting of the minds. Each artist has a vision for arriving at beauty the hard way, and Coltrane often credited Monk with helping him find his distinctive style. Here, it’s almost possible to hear Coltrane working out his ideas. On opener “Ruby, My Dear” (one of Monk’s earliest tunes), Coltrane and Monk are in lockstep, pushing each other through the slow movement of the track.

Where not to start: Monk helped develop the musical ideas that would become bebop, the style that evolved during World War II, partly as a reaction to mainstream swing and the country’s dance craze. With Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and others, Monk found new directions in jazz, excluding an earlier generation of musicians only versed in swing. With its fast tempos and use of the chromatic scale in solos, bebop can be a tough pill to swallow for beginners.

By age 30, Monk had already written some of his most important tunes—“’Round Midnight,” “Off Minor,” “Ruby, My Dear,” “Well, You Needn’t”—and began recording them for Blue Note in 1947. On these early sessions, many of the hallmarks of Monk’s style are already well in place, and lately there’s been a renewed interest in them from jazz fans. But, for starters, the recording quality is a bit harsh. Often, the drums sound like they were recorded in an elevator shaft. “Well, You Needn’t,” recorded with just a trio and no soloists, is all sideways jabs and slamming cymbals. It’s Monk graduate school, for sure. “To work with Monk is a challenge,” wrote Orrin Keepnews, Monk’s producer, citing both the complexity of his compositions and his persistent perfectionism. But, in the end, the joy of Monk’s music is that it can be listened to over and over again. It never gets old; there’s always something new to discover about it.