While We’re Young is essentially Noah Baumbach’s Neighbors

Laying out its anxieties right there in the title, While We’re Young is Noah Baumbach’s midlife crisis movie, a funny, talky portrait of an aging artist reaching for the vitality he sees in some younger friends. Coming from the neurotic New Yorker behind Frances Ha and The Squid And The Whale, it also feels like the latest stage in a career-long project—an attempt to chart every stumbling step of post-adolescence, from the shell shock of the late-teen years to the scary free fall of life after college to the self-imposed waiting station occupied by grownups who refuse to grow up. Baumbach has gone softer than usual, not probing as deeply into his slow-to-mature characters. But that may be because he seems to have made a certain peace with delayed development. Adulthood, this less-caustic comedy concludes, is a perpetual work in progress.

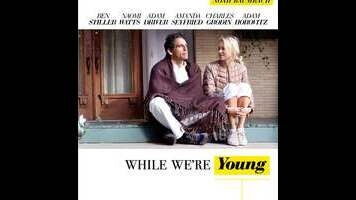

If that sounds a tad like the philosophy that might drive a Seth Rogen vehicle, it’s also fair to identify While We’re Young as a kind of art-house Neighbors, exploring as it does the generational gulf between a fortysomething couple and the twentysomething spouses they befriend. Reuniting with the star of his Greenberg, Baumbach casts Ben Stiller as Josh, a documentary filmmaker caught in a decade-long rut. (Any attempt to explain the six-and-a-half-hour, Shoah-esque opus he’s been toiling away on inevitably ends with a default, “It’s really about America.”) Revitalization comes in the form of Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried), the two bohemian lovers who crash Josh’s continuing-education class and quickly insinuate themselves into his life. Cornelia (Naomi Watts), Josh’s producer wife, is initially suspicious of the pair’s intentions, but she soon caves to their flattery and good spirits.

There’s a certain sitcom easiness to the film’s premise, which hinges on both the mild absurdity of Josh and Cornelia not acting their age—he buys a hipster hat; she takes hip-hop workout classes; they both try mescaline—and some pot-shots taken at the pretentiousness of youth culture. But Baumbach handles this potentially groan-worthy material with verbal and visual wit, the effervescent snappiness that’s become his signature. One early montage feverishly juxtaposes the older couple’s reliance on modern technology with the younger couple’s embrace of vinyl and VHS. (“It’s like their apartment is full of everything we once threw out, but it looks so good the way they have it,” declares Cornelia.) Impeccable casting helps sell the shtick: Stiller is better here than he’s been since… well, Greenberg, and Watts capitalizes on the rare opportunity to flex her comedic muscles. As for Driver, he exhibits his usual gift for hilarious cool-kid vapidity, adding a chameleon-like careerist to his résumé of young cads.

For a film that opens with an Ibsen quote, While We’re Young deals in broad strokes; arguably its funniest moment is the one that involves a vomiting drug trip. But Baumbach is never less than shrewd in the way he links his protagonists through insecurity. The movie eventually reveals that Cornelia’s father, wonderfully played by Charles Grodin, is a Wiseman-like giant of the documentary scene, and that Josh once thought of him as a mentor, before distancing himself when he came to resent the connections everyone drew between their careers. What Josh sees in Jamie, an ambitious budding documentarian, is not just the enthusiasm of youth, but also an ego-stoking protégé of his own. Likewise, Cornelia warms to Jamie and Darby’s whirligig lifestyle mainly as an excuse to put some distance between herself and close friend Marina (Maria Dizzia), who’s just become a mother and won’t stop bugging her bestie to follow suit. (Beyond the laughter, this is a sharp meditation on the agony of trying to decide whether to sacrifice your old life for the one a baby will create in its place.)

Biting off a little more than he can chew, Baumbach eventually takes the movie in an unexpected direction, hijacking his culture-clash narrative with a late-breaking treatise on the ethics of documentary filmmaking. (If Grodin’s character represents the fading legacy of Direct Cinema trailblazers, Jamie is the new face of fact-fudging, navel-gazing nonfiction—a star for the Catfish era.) But even as the film builds to a pair of overlapping speeches, Baumbach subverts his own big finale. He’s too smart, too idiosyncratic, to offer conventional catharsis. There’s an unmistakable hint of autobiography here; when Cornelia’s father accuses Josh of moving from approachable movies to “ungenerous” ones, it’s easy to wonder if Baumbach isn’t commenting on his own run of harsh character studies. On some level, perhaps the filmmaker has exhausted his capacity for cruelty. If Greenberg took that quality of his work to its outer limit, While We’re Young offers a more charitable, even hopeful vision of growing older, one that locates a certain freedom in realizing—as its fortysomething characters do—that it’s okay to be young and dumb and to be old and dumb. The adults, like the kids, are all right.