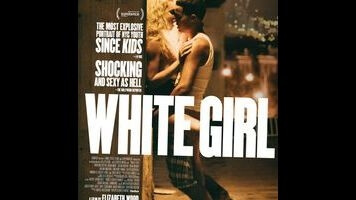

Ridgewood is the type of neighborhood where young people move attempting to stay ahead of gentrification—and in doing so, contribute to it at the same time. This is kind of a fucked-up system, too, and White Girl seems to think it’s addressing all attendant issues by telling the story of Leah’s flirtation and infatuation with Blue, whom she first approaches while looking for more weed. “I really like drugs,” she later explains, half-giggling. Blue and his friends are less capricious about recreational use, sticking to pot even as they sell harder stuff. The movie, conscious of its white-girl vantage point, clearly positions the drug dealers as less sleazy or predatory than, say, Leah’s internship boss (Justin Bartha) at a trendy magazine. When Blue gets arrested, Leah decides to do anything she can to help him.

As Leah gets closer to Blue and their worlds bleed into each other, writer-director Elizabeth Wood toggles between the sweat-and-neon sheen of New York at night and the harsh white light of the next morning. It’s a striking balance of extremes that quickly becomes monotonous. White Girl tries to be knowing about New York, and it may well portray a certain cross-section of subcultures with stunning accuracy. But despite the variances in socioeconomic status among the characters, its point of view feels limited—everyone is kind of a coked-out bore except Blue, a bore who doesn’t snort coke.

The movie doesn’t really purport to discuss addiction, but Leah’s single-mindedness brings the condition to mind. Saylor, who sounds a little like Anna Paquin, uses a stooped but forward-leaning stance and dyes her hair platinum blond to come off like a teenager affecting an older posture. It’s a committed performance without much going on underneath. White Girl clearly sees itself as some degree of provocation; the sex scenes are too explicit and the racial/gender dynamics too loaded to claim otherwise. But its idea of drama is to have all of its characters make a bunch of haphazardly bad decisions as they stumble through New York steaminess. A micro-scene where Leah walks in on her roommate Katie (India Menuez) having sex before abruptly cutting away feels like the film really wants to cram some additional sex into its 88 minutes. What’s really shocking, given the thinness of the psychology, is that this story is apparently rooted in autobiographical details from Wood’s life.

Wood pulls off a few virtuoso moments, like Blue’s arrest scene. He’s at a fast food restaurant with Leah, and steps to talk to a jonesing customer. In the time it takes Leah to pace aimlessly across the restaurant, Blue gets arrested—the action takes place in a combination of the background and off screen, until Leah sees him thrown against the window. The cops leave without realizing Leah is holding even more coke (or maybe that she’s involved with Blue at all), and there’s a rough poetry to the suddenness of her life being thrown from dabbling in danger to genuine chaos. But ultimately, this is a movie of ogling: of sex, of hedonism, and, eventually, of terrible situations without solutions. Ultimately, Wood doesn’t have much time to treat the romance between Leah and Blue with any more depth than the characters. It’s a shame. Her final shot would have real power in a richer, more perceptive film.