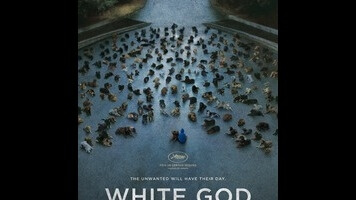

A teenage girl bikes alone down an empty city street, peddling with purpose. Suddenly, as she passes an intersection, she is no longer alone. From around the corner come dozens of stray dogs of all sizes and breeds sprinting in her direction. Is she fleeing from the animals? Or is she leading them? It is, without question, the most striking moment in White God, an acclaimed Hungarian whatsit fresh off the festival circuit. And though the set piece arrives about two-thirds of the way into the story, audiences won’t have to wait that long to experience it. Performing a common structural trick, designed to grab attentions immediately, director Kornél Mundruczó opens his movie out of sequence, with a scene that occurs much later in the timeline. It’s a smart play; not only will viewers be hooked by this dreamlike spectacle, they’ll be itching to know just what kind of film they’ve stumbled into.

Two hours later, many may still be wondering. A hit at last year’s Cannes, where it rather inexplicably trounced Force Majeure for the top prize in Un Certain Regard, White God at times resembles everything from The Birds to Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes to a live-action Oliver & Company. It’s ruthless but sentimental, gritty but fanciful, drop-dead serious but also a little impossible to take seriously. What the film has going for it, beyond general audacity, is a handful of memorable images, most of them involving the creative use of real rescue dogs. Canine lovers may have a deeper appreciation for what it attempts, though only if they can stomach the kind of simulated animal cruelty that made passages of Amores Perros so difficult to sit through.

After the hypnotic, out-of-time prologue, White God flashes back to show how Lili (Zsófia Psotta), the 13-year-old girl from the first scene, becomes separated from her beloved pet pooch, Hagen (Body). Given the hybridized nature of the plot, it’s apt that crossbreeding plays a role: A new law has made it illegal to own mongrels—the government will tolerate only purebreds—and so Lili’s stern, divorced father (Sándor Zsótér) drops her best buddy off in the streets of Budapest. At this point, Mundruczó begins chronicling the pup’s plight, and suddenly this neorealist coming-of-age story is alternating with an R-rated Homeward Bound. As Hagen makes his way across town, he falls in and out of the clutches of dogcatchers, dog fighters, and other general dog abusers. (Hungarians are cat people, it would seem.) The plucky pooch also amasses a small posse of fellow mistreated mutts, his Dickensian pack. Meanwhile, Lili pouts and deals with mean masters of her own: her heartless dad and a testy band instructor at her school.

Were White God to commit to its big POV swap, viewing all subsequent events through Hagen’s almond-shaped eyes, it might have earned a certain conceptual integrity. Instead, Mundruczó uselessly bifurcates the narrative and our sympathies, cutting away constantly to the dull kitchen-sink drama of Lili and her father. The folly of this decision becomes clear during the final act, when the film wildly, uneasily blends nature-run-amok horror and revolution parable. One assumes the title is meant to evoke the cult classic White Dog, which used a genre framework to have frank discussions about race. But Mundruczó exhibits little of Sam Fuller’s gift for visceral violence—the attack scenes here flirt with all-out goofiness—and his attempts to position the climactic action as a metaphoric class/race war are hindered by his refusal to completely, ahem, adopt the perspective of his non-human characters. As a curious hodgepodge of ideas, White God gets by. But the releasing-of-the-hounds at the start is a bad omen. The film, like the dogs, mostly goes downhill.