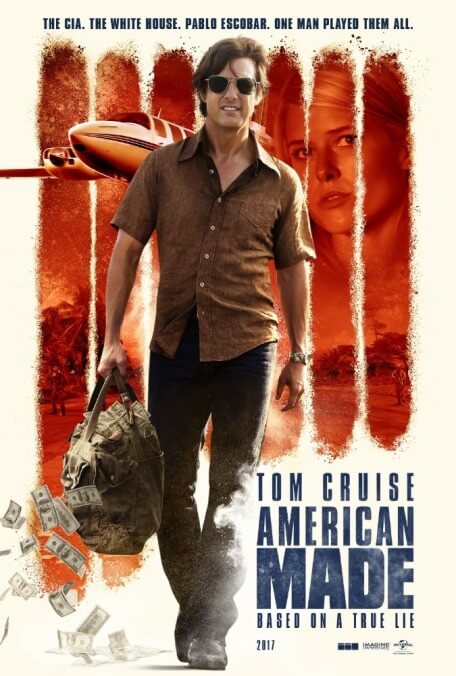

Who needs a Top Gun sequel when you’ve got Tom Cruise flying high in American Made?

For years, dating back to his post-2000s retreat into damage-control movie-star mode, Tom Cruise has been threatening to make a sequel to Top Gun, the 1986 flyboy picture that upgraded him from star to superstar. Belatedly sequelizing one of his most beloved and most terrible movies has always been a dubious proposition, but it seems particularly strange in the wake of American Made, which functions as a combination prequel and corrective to Top Gun. In the newer movie, Cruise takes advantage of his slower-than-average aging process to play Barry Seal, a real-life pilot who worked by turns for the Colombian drug cartels and the U.S. government in the late ’70s and early ’80s. The movie’s Barry, stultified by his commercial flying work, has such a need for speed that when he’s approached by a CIA operative calling himself Schafer (Domhnall Gleeson) offering a gig spying on Central American communist groups from a plane, he can only laugh in amazement and say yes.

Actually, there’s a little bit of nervousness in Barry’s smile as well. Though he shows a jones for pointless risk-taking early on when he jostles his copilot awake by turning off a jet’s autopilot function, Cruise downplays both his shit-eating grin and his late-period stoicism here. He goes (relatively) low-key in a movie that’s already amped enough. Director Doug Liman, who commanded Cruise’s best non-Impossible mission of the past decade with Edge Of Tomorrow, throws back to the jitters of his itchy earlier movies like Swingers and Go. He establishes staccato editing rhythms early on, intercutting the monotony of Barry’s airline job with his wife Lucy (Sarah Wright Olsen) preparing for his return.

Barry accepts the CIA job with his family in mind, hoping to make some extra dough. When he’s left disappointed with the money, he becomes amenable to a smuggling offer from a drug cartel that includes Pablo Escobar (Mauricio Mejía). And when that goes slightly awry, Schafer gets him involved in supplying guns to the Contras opposing the Sandinistas of Nicaragua (initially uninterested in the weapons, the Contras promptly relieve Barry of his aviator shades). This also provides good cover for further drug-related operations, and so on. Barry takes little convincing from either side of this tug-of-war, which means the story is weighed down by neither a lot of tedious soul-searching nor a strong sense of dramatic tension.

That breeziness, and a sense that Liman cut this movie together from a whole mess of footage, doesn’t preclude some nice smaller moments from Cruise, like the way he runs his tongue over the site of a recently departed tooth as he considers a particular business proposition. To some degree, his Barry remains a pragmatic enigma, happy with his reputation as a “gringo who always delivers” and the opportunity to sweat through some scrapes and close-calls without much hint of inner life. Schafer doesn’t really call him out on his moral flexibility, maybe because Barry’s shell-game version of the American dream—at one point, he both owns an airport and buries satchels of cash in his backyard—isn’t so different from the half-baked operations that require his services.

Without the traditional Cruise cockiness or Scorsese-style coke-fueled bravado (though he winds up covered in the stuff at one point, the movie version of Barry never seems to partake in anything harder than celebratory liquor), Liman turns the movie into an odd-angle retelling of Reagan-era foreign-policy screw-ups. It’s an entertaining one, shot in a variety of textures by City Of God cinematographer César Charlone: Exterior shots often pop with saturated color, while interiors have the faded look of a CRT display. Cruise also delivers the obligatory running narration (with his in-and-out Southern accent) straight into an old-school VHS camcorder.

American Made has such style and energy that its hasty patchwork of a narrative becomes a kind of charm unto itself, even when it means losing track of talented actors. The movie gins up a whole supporting roster of barely-used characters, including husband-and-wife cops in Barry’s new home of Mena, Arkansas, played by Jesse Plemons and Lola Kirke in what feels like the trace remains of what was once a subplot. One confrontation with Barry’s feckless, frequently shirtless brother-in-law (Caleb Landry Jones, the consummate unredeemably creepy brother-in-law of 2017) abruptly cuts out for a wholly unrelated on-the-job scrape.

As a high-wire criminal balancing act in the vein of Goodfellas or Blow, American Made is adequate (nowhere near the former; more enjoyable than the latter). But as a Tom Cruise text, it’s something else. Liman turned a cowardly, supercilious version of Cruise into a hero in Edge Of Tomorrow through time-travel man-hours; here, he imagines a workaday version of the actor, waiting to unleash his daredevilry on the world. That’s where the rebuke comes in: The movie may be heightened, but this Tom Cruise ultimately lives through some ’80s crashes, rather than the now-kitschy fantasy ’80s of Top Gun. He’s a maverick pilot who ultimately has no place to go but down.