Why are so many big-studio musical numbers so bad?

The Academy Awards may have questionable influence on the moviegoing public at large, but almost 16 years after Chicago won Best Picture, it’s safe to say that the Oscars helped bring the live-action big-studio musical back to life. The genre doesn’t see as many annual releases as, say, superhero pictures or horror movies, but it’s still achieved relative consistency at the box office, with a near-annual occurrence of $100 million-plus hits, usually released around Christmas, like the recent Mary Poppins Returns. The past five years alone have seen high-profile Broadway adaptations (Into The Woods), originals (The Greatest Showman), even entries in franchises (Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again), along with the usual semi-musical showbiz stories like A Star Is Born and Bohemian Rhapsody. In terms of popularity and visibility, movie musicals are thriving to a degree unseen for decades, as are their televised counterparts.

Yet for all the seemingly audience-pleasing hits the genre has accumulated since Chicago, shockingly few of them have anything resembling a classic, canon-ready musical number—a sequence that deserves a place in the pantheon of great musicals, to say nothing of a full film worthy of this designation. This is all the more confounding because Hollywood has established a pool of go-to movie musical directors—again, something that was practically unthinkable for decades prior. Rob Marshall (the aforementioned Chicago, Woods, and Poppins), Bill Condon (Beauty And The Beast, Dreamgirls), and Adam Shankman (Hairspray, Rock Of Ages) have all directed multiple musicals, and Tom Hooper, who directed the hit adaptation of Les Miserables, is joining the the club next Christmas with Cats. Not all of these directors have made exclusively bad movies. But most of the big Hollywood musicals of the past decade are more notable for their performances than their filmmaking.

There isn’t one set of standards for a great musical sequence; they can produce efficient, emotionally direct storytelling, or they can exist for the sheer pleasure of themselves, to name two popular options. (The consensus choice for the Great American Movie Musical, Singin’ In The Rain, has scenes in both of those categories.) But the best musical scenes tend to fight against the perfunctory nature of so many middling-or-worse films, using an inherently more presentational style to express a distinctive feeling. Obviously, any kind of scene can be made emotionally expressive—or, for that matter, kinetically thrilling, or intentionally opaque. But just as great action sequences go beyond showing a barrage of fists or gunfire, musical scenes are particularly effective when they summon more than some competent coverage of what’s happening on screen. If a musical is going to have its characters burst into song and so gloriously upend the dull standards of realism, it ought to be ready to burst with them.

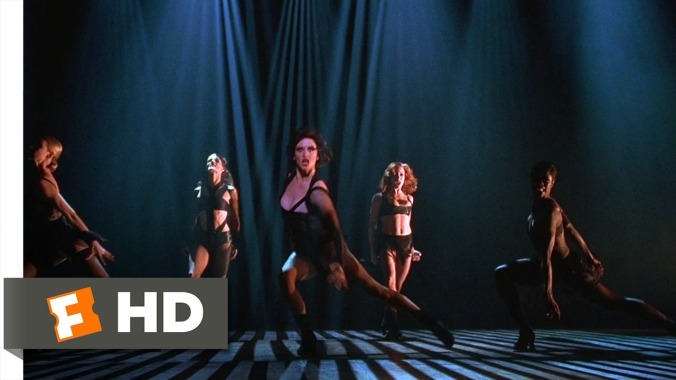

This is especially true in the wake of A Hard Day’s Night and the wide range of music videos that followed, initially appearing to replace older musicals but eventually integrated back into their vocabulary—at least in theory. These influences still appear to somehow vex a number of frequent musical-makers. Marshall pioneered a worst-of-both-worlds approach to musical directing with Chicago, where he paired music-video-style fast cuts with a theatrical-style minimalist-stage presentation, and then repeated it with much worse material for the disastrous Nine. Cutting in a musical can be a gift to the form; Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge uses the tempo of his editing as an additional performer in his musical numbers, from the frenzy of his introductory material to the tension-building clarity of the anguished “Roxanne” number late in the film. Chicago and Nine lack both modulation and genuine kineticism. Marshall cuts like he’s determined to fulfill an audience’s demand for spectacle—like fast cuts and some frame-rate adjustments are, on their own, equivalent to cinematic razzle-dazzle. That razzle-dazzle is very much a part of Chicago’s narrative, but the musical sequences aren’t dazzling distractions so much as pummeling and frantic, a faking of confidence that doesn’t particularly comment on its own fakery.

Even as Marshall has experimented with less aggressive editing styles in later musicals, his cutting doesn’t have much of a pulse. Mary Poppins Returns has no stage roots to consider, indulges in plenty of purely cinematic devices with its use of animation and special effects, and in many of its numbers wants only (or at least primarily) to delight. Yet even its highlights, like its enjoyable centerpiece live-action/animation number, don’t feel directed so much as traffic-controlled, with Marshall still using stage effects and film trappings without really fusing them in a meaningful way. Once again, the characters appear on a stage, and the movie cuts around to different vantage points.

There’s a similarly flattening effect at work in Bill Condon’s lavishly appointed re-do of Beauty And The Beast. The animated 1991 original hands him an instant-classic musical number in the form of “Be Our Guest,” a number that both displays the magic of an enchanted castle and, in a sneakily clever sort of way, hints at the pent-up frustrations of humans trapped as furniture and flatware without anyone to dazzle. Instead of teasing out this (or any other) emotion, Condon struggles to sink what should be the movie’s easiest layup. It fails to match the energy of the animated original in large part because Condon seems overwhelmed by his potentially spectacular visuals and uncertain of how to find his focus. He keeps resorting to push-ins and cuts that showcase the CG version of Lumiere the candlestick, as if the mere sudden sight of a singing candlestick will send viewers into paroxysms of delight, no matter how often it happens over the course of three minutes. (And maybe he was right; the movie made a billion dollars). Instead of conveying excitement or any kind of emotion, the sequence feels like it’s sweating to keep up with the brilliance of the song—even as the song itself sounds slower, whether it’s been actually slowed to match the sluggishness of the filmmaking or just seems that way.

Some purists might argue that excessive cutting simply plays against the strength of the musical—that it doesn’t allow enough space to simply regard the performances at play. Setting aside that oversimplification (again, look to Moulin Rouge, which is not a showcase for dancers or powerhouse singing, but still alive with movement and color), most current musical directors don’t quite know how to take advantage of longer takes, either. Marshall’s Into The Woods uses more sustained, fluid camera work than his other musicals, but two of its more visually distinctive and less busy numbers, “Agony” and “On The Steps Of The Palace,” still accompany their performances with such unadorned imagery (picturesque music-video anguish and slow-motion contemplation, respectively) that they almost go back around to staginess. The visuals make “Agony” slightly funnier and “Palace” slightly more reflective, but they mostly leave the heavy lifting to the performers. Similarly, Tom Hooper’s Les Miserables uses long takes and live recording to capture actors singing on-set, and comes closer than most recent big-budget musicals to a canon-worthy scene when the camera is trained on Anne Hathaway singing “I Dreamed A Dream.” But Hooper’s bag of tricks is limited enough that the novelty wears off later in the film.

At least Into The Woods and Les Miserables are clear about what the audience is supposed to be looking at, and why we might feel a certain way about it. Adam Shankman is a go-to choreographer, but when he directs his own musicals, even the most ebullient numbers include indifferently framed shots that look, variously, like moments from a making-of special, first-person accounts of what it’s like to be an extra in a musical crowd scene, and overheads captured by a low-flying drone, all cut together senselessly and with endless reaction shots. There’s palpable enthusiasm in this approach, but Hairspray and Rock Of Ages rarely settle into a proper rhythm; they’re too busy jumping up and down at the prospect of some catchy, upbeat songs receiving the full-on musical treatment. They’re musical numbers as acts of meta fandom, gesturing toward youthful optimism without actually embodying it.

In a perverse way, it makes sense that arguably the most-loved musical from this period is also arguably the worst-made of the bunch. A great musical brings together performances, editing, choreography, and framing like an orchestra. This makes some of the numbers in Phyllida Lloyd’s Mamma Mia! akin to a bunch of musicians bashing away on different tunes simultaneously while grinning like maniacs. The performance of “Dancing Queen” that’s shot and choreographed like a tourism-board lip dub is probably the movie’s biggest-scale folly, but it truly an reaches its apex not there, nor with Pierce Brosnan’s admirably boisterous “S.O.S.” caterwauling, but during Meryl Streep’s performance of “The Winner Takes It All.” The song, which she sings at Brosnan standing cliffside, is staged as dully as any perfunctory dialogue scene, keeping Streep and Brosnan physically apart while still forcing them to flail around in each other’s presence. It also features a baffling imitation of a jump-cut where a medium close-up of Streep cuts seamlessly to another medium close-up with inexplicably adjusted lighting that shifts the background ocean to a darker blue instead of a blinding white. It’s as if Lloyd was directing a live performance and found a better angle mid-sequence.

Mamma Mia’s whole deal is its unashamed cheesiness, but it’s entirely possible to make something in that mode without resorting to frazzled indifference. In fact, the recent Mamma Mia sequel does just that; it’s not much smarter than its predecessor, but the best musical numbers are downright zippy: coherently shot, playful, and allegiant to the Mamma Mia ethos of maximum cheesiness. The “Waterloo” sequence may be ridiculous, but it squares with the movie’s heedless, sometimes flaky ideas about true love. There’s also genuine skill behind the best numbers in the similarly dumb The Greatest Showman, which takes advantage of film’s ability to cut in closer to its performers during Hugh Jackman and Zac Efron’s performance of “The Other Side,” drawing the audience into their plans rather than simply reveling in the footwork and spectacle. Against some of the competition, these enjoyable sequences look like triumphs.

Still, there must be better solutions to making big-studio musicals than trying to replicate the competence and occasional inspiration behind Mamma Mia 2 and The Greatest Showman. Amazingly, a lot of criticism of contemporary musicals still turns back to the actors, complaining about how many film performers simply can’t sing (or dance, or do backflips). But the notion that movie actors need Broadway-level vocal chops is an outdated one that refuses to acknowledge the ways that movie musicals can and should be different from their theatrical counterparts.

The enduring focus on performance might partially explain why so many filmmakers fail to synthesize all of their elements into truly memorable sequences. Even if some modern musicals overindulge in fast edits, they often seem like they’re overcut because of the sheer amount of footage at their disposal, in an attempt to capture as much of their considerable production values as possible. This mode of filmmaking is superficially splashy, yet often tenuous and overcautious compared to, say, the exuberance of the Los Angeles drivers emerging from their cars to sing and dance through La La Land’s opening single shot, or the flirty sweetness of the simply choreographed numbers in Stuart Murdoch’s God Help The Girl, or the melancholic intimacy of Markéta Irglová walking down the street at night, singing along to a portable CD player demo in Once.

These movies, along with a few bigger productions like Julie Taymor’s Across The Universe (uneven as a movie, but undeniable as a collection of some great sequences) and Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge, are less self-conscious about both the genre of musicals and the medium of film. They don’t feel beholden to either multiplex audiences or theatrical purists. Maybe that’s also why Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd works better than Marshall’s Into The Woods. Burton has been criticized for rehashing his personal aesthetic endlessly, but he appears more comfortable in his particular wheelhouse than many go-to musical filmmakers are in theirs.

Other idiosyncratic filmmakers have expressed some level of interest in making a musical, and plenty more have the kind of showmanship that would serve the genre well. But relatively few have committed. It could be that the semi-experimental musicals made by ’70s movie brats hang over other ambitious filmmakers like storm clouds: Francis Ford Coppola’s One From The Heart and Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York are well-known as costly boondoggles, while Steven Spielberg’s similarly pilloried 1941, though not a formal musical, has a similar level of choreography and would-be lightness that eventually turns lugubrious. (Spielberg has feinted toward musicals several times since, including the opening of Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom. He’s currently prepping a remake of West Side Story, supposedly shooting this summer.)

Musicals make great passion projects. Unfortunately, passion projects often make for fascinating failures, and the value of the “fascinating failure,” while high to plenty of cinephiles, is always a tough sell to big studios that have only gotten more risk-averse. Ultimately, studios have opted for musical directors who appreciate the genre so much that they want to protect it, still fighting against the perception that musicals are a risky proposition. As a result, sometimes even the better recent large-scale musicals feel like the filmmakers are sharing those protection strategies with each other. How else would production numbers from Into The Woods wind up vaguely resembling those from Les Miserables? It’s a nice gesture toward this much-loved material, but as the characters in Woods sing: Nice is different than good.

Even if, say, Spike Lee, Michel Gondry, Leslye Headland, Spike Jonze, Andrea Arnold, or Ryan Coogler wind up evincing little interest in furthering the genre, or if Spielberg’s long-waited attempt falls flat, the traffic-directing approach to the genre should evolve. Otherwise, it could become a release-date placeholder, an acceptable holiday alternative to Star Wars but little else. For all of their perceived competition with the stage or the discomfort they supposedly cause some audience members, there’s something particularly transporting about a great cinematic musical, or even just a great sequence or two. (Get enough of the latter together, and maybe you wind up with the former.) Lately, it’s an experience happening more often in indie productions. For that process to work on a larger scale, the cautious reintroduction phase of the musical needs to end.