Why aren’t you fired yet? 14 television characters who inexplicably held onto their jobs

Someone call HR, here are 14 television characters who inexplicably held onto their jobs.

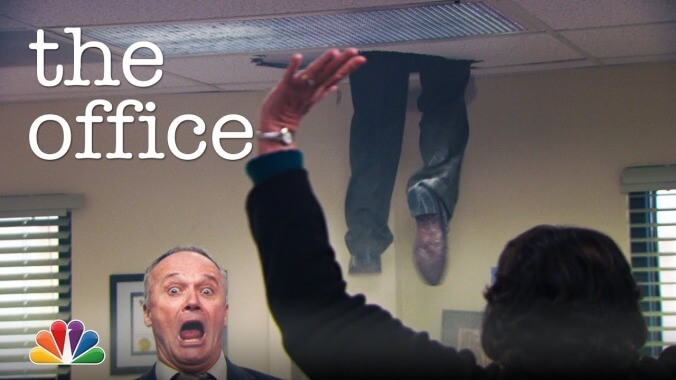

With The Office’s fake-documentary aesthetic and mundane workplace setting, NBC’s American version of the show typically thrived for a realism uncommon to network sitcoms. (It looked especially grounded when compared to fellow Thursday night comedies Community and 30 Rock, which frequently leapt into surrealistic flights of fancy.) But in at least one respect, the show demanded a complete suspension of disbelief: How, longtime viewers had to wonder, did transgression-prone paper-pusher Dwight Schrute manage to remain employed at Dunder Mifflin throughout The Office’s nine-year run? Sure, Michael Scott fired him once—a termination that lasted exactly one episode—but that was for betraying his trust, not for any one of the lawsuit-worthy incidents he was involved in before or after. Over the course of the series, Dwight quoted Hitler and Mussolini during an acceptance speech, egged a potential client’s business, kidnapped a pizza boy, had sex with a co-worker on company property, fought another co-worker on company property, viscously dismembered a Rescue Anne doll, and caused mass panic (and a heart attack) by staging a fake fire. (Those last two actions happened within days of each other, by the way.) But the series reached a point of no return, at least as far as plausibility is concerned, when Dwight discharged a firearm in the office, temporarily deafening Andy, and still held on to his job. Great salesman or not, there’s no coming back from that.

At first glance, nearly every resident of Springfield could qualify for inclusion in this list. And while many of them have been dismissed from their jobs at some point, it’s usually due to circumstances beyond their control: Santa’s Little Helper is to blame for Principal Skinner’s brief leave from Springfield Elementary in “Sweet Seymour Skinner’s Baadasssss Song,” and Apu only loses the Kwik-E-Mart job in “Homer And Apu” because of a catch-22 in company policy. It’s the town’s public servants who have the most surprising resilience—lacking the natural charisma and family largesse of Mayor “Diamond Joe” Quimby, Clancy Wiggum displays all the competence and qualifications of a police chief who earned his station by merely being the first volunteer. Wiggum is easily distracted, dangerously lazy, and often dependent on the assistance of the Simpson children to crack a case (particularly when Sideshow Bob is involved). The show couldn’t go 25 years without at least stripping Wiggum of his badge once or twice, but he’s ended up crawling his way back each time—though he required a Simpson boost in these events as well. Were it not for Homer taking pity on the destitute Wiggum in “Homer Vs. The Eighteenth Amendment”—allowing the once-and-future-lawman to bust up the Beer Baron bootlegging ring—Springfield would remain under the sober thumb of G-Man Rex Banner. Would the town really be worse off?

South Park’s sexually fluid schoolteacher has actually been fired once and suspended once, but he always quickly finds his way back to his fourth-grade classroom, where his lesson plans largely focus on racist stereotypes, pop-culture ephemera like Game Of Thrones history, blatantly wrong information, and graphic sex acts. Like Springfield, South Park is a town full of comically awful incompetents who should be fired (or booted out of office, or separated from their children) for everyone’s good. But even in this environment, Mr. Garrison stands out, largely for the way his teaching career focuses half on his personal life and half on awful misinformation. (“Gay people are evil, right down to their cold black hearts, which pump not blood like yours or mine, but rather a thick, vomitous oil that oozes through their rotten veins and clots in their pea-sized brains, which becomes the cause of their Nazi-esque patterns of violent behavior.”) Throughout the series, he plays out a variety of lurid sexual and gender-identity dramas, always expecting a bunch of elementary-school students to act as his therapists and emotional support system. And yet he’s still teaching. Even when he crams a gerbil into his lover’s ass in the classroom—in the hope of getting fired and suing for homophobic discrimination—he just gets praised for bringing diversity into his workplace.

Wouldn’t it be folly for a major-market radio station to give a plum time slot to a stuffy psychiatrist with no broadcasting experience? Definitely, though good luck convincing the management at KACL, the fictional Seattle talk-radio station on Frasier. KACL keeps their Freudian bumbler on the payroll despite the fact that Frasier never quite shakes his first-day jitters. He routinely misses cues, stretches commercial breaks so that he can attend to personal matters, and cuts segments short. When the station let Frasier put together a special—a murder mystery to mark its 50th anniversary—the production collapsed in a mess of infighting and incompetence. But surely Frasier’s most fireable offense was the night he had loud, passionate sex live on the air, broadcasting rapturous cries of “dirty girl!” to all of Seattle. He was saved from the ax in that case only because the “dirty girl” in question was the station manager at the time. Perhaps Frasier’s brooding baritone charm is what keeps the listeners happy, too—or maybe they just tune in to hear how Frasier will screw his show up next.

Television is littered with well-meaning but incompetent education officials, but Community’s Dean Craig Pelton stands apart for his combination of ineptitude and sociopathic behavior. It’s not just that under his watch, Greendale Community College is constantly on the verge of closing down, though his battles with City College and Greendale’s own Air Conditioning Repair School suggest new leadership might benefit the school immensely. It’s also that he seemingly spends the majority of his time trying to ingratiate himself to the show’s central study group, at the expense of the rest of the student body. Furthermore, it’s incredibly unlikely by this point that Jeff Winger would not have sued the Dean for harassment, if for no other reason than it might potentially accelerate his graduation. The concept of reality, though, is fluid within the world of Community.

Like a version of The Dick Van Dyke Show in which Rob Petrie has Alan Brady’s job (and blows up the ottoman during each week’s intro sequence), Home Improvement split itself between the work and domestic lives of repair-show host Tim “The Tool Man” Taylor. The connective tissue between those two spheres was Tim’s unending path of destruction, a trail blazed with the latest gizmos from his show’s main sponsor, Binford Tools. Tim Allen’s Home Improvement character is unusual among TV pitchmen, who don’t tend to stay on the payroll when they’re regularly broadcasting the hazards of their employers’ product line. But Tim’s Tool Time is always portrayed as great entertainment, and he isn’t an inferior handyman—his undoing is an insatiable lust for “more power” (and a persistent refusal to read instruction manuals). Though this was a trait inspired by the exaggerated alpha-male antics of Allen’s stand-up comedy, years later it looks like a parody of TV personalities who keep their jobs no matter what kind of dumb shit they may do or say in public.

“I can’t work too hard; I almost gave blood today,” Dilbert’s co-worker Wally says in one episode of the animated TV show based on the office-comedy comic strip. That dodge is typical of Wally, who always has an excuse to get out of accomplishing anything: When a corporate takeover looms, and Dilbert asks his co-workers if they’re considering retiring, Wally answers, “Retire? From what? I don’t do anything now except surf the net… Besides, I really like the coffee here.” And yet, thanks to the obliviousness of their incompetent, pointy-haired boss and Wally’s extreme talent at making excuses and looking like he’s working, his job never seems at risk. His co-workers have certainly noticed that he’s dead weight, though; they note at one point that they’ve started using his name as a pejorative, “As in ‘He’s a total Wally,’ or ‘I gotta take a Wally.’” Created as an extreme parody of the lazy, entitled, do-nothing co-worker, Wally keeps his job largely because if he got fired, someone else in the office would have to take up his comedic niche.

Funny though she might be, Karen Walker makes a terrible personal assistant. The tipsy socialite made a deal with Grace that she could “work” at Grace Adler Designs as long as she never had to actually do anything; Grace paid her, but she would never cash any of the checks. (This backfired deeper into the series, but worked out in the end.) Still, though Grace didn’t have to compensate Karen and somehow managed to weasel both health insurance and a Christmas bonus out of her wealthy employee, she did have to deal with her nasty snark for eight hours a day. Not even Walker’s social connections and eye for decent interior design could make that worthwhile.

For eight seasons, Dexter Morgan cut a bloody swath through the serial killers, drug dealers, and human traffickers who made Miami their hunting ground. He avoided capture as long as he did thanks to a mix of dumb luck and careful planning, but the greatest factor he had in his favor was the gross incompetence of the officers of Miami Metro. LaGuerta, Batista, Deb, Quinn, and Masuka all seem to spend more time furthering their careers and personal lives than catching bad guys; they slept with fiancées of rivals and opened restaurants when their intuition should have told them what their mild-mannered forensics expert was up to. Even when Dexter’s secret was uncovered—which happened at least three times in the life of the series—the officer who figured it out never shared the truth with colleagues and was eventually blown up, shot in the head, or taken off life support.

If the Tunt family fortune helped fund ISIS, Cheryl’s role as Malory Archer’s secretary would make perfect sense. But that wealth has had absolutely no impact on the day-to-day operations of the agency. Cheryl spends her days not answering phones, indulging her arsonist tendencies, and oversharing her personal fantasies. Her presence never adds anything except an extra layer of sarcasm to the proceedings, and quite often her poor work ethic puts her co-workers’ lives in danger. (In a normal office, apathy isn’t the worst quality an employee can possess; in an office that deals constantly with life-or-death situations, such negligence is downright sadistic.) Cheryl has said that her hatred for the other ISIS employees helps her get up in the morning. It’s unclear, however, what the company gets out having her around.

Newman’s role on Seinfeld was basically to be Jerry’s archenemy. The comedian needed someone to despise, and his contemptuous catchphrase (“Hello, Newman”) is still uttered to this day. But the slovenly mail carrier served another function as well: Seinfeld and Larry David used him to take out all their frustrations with the U.S. Postal Service. Most of the time, Newman was completely apathetic. Once, he just stopped delivering mail, and Jerry bailed him out; Newman got in trouble because Jerry was too efficient. Other times, the job drove him nuts, as he once . Still other times, he engaged in illegal activity, like when he and Kramer hatched a scheme to use a mail truck to ferry bottles to a state where they could get a higher deposit back for them. That particular scheme ended with the truck completely destroyed, but the next week there was Newman, back in uniform.

Unlike Newman, Cliffie was proud of being a postman, to the point where he considered the duty to be almost like serving in the military. But given how much of his life he spent at Cheers, it was hard not to wonder when he possibly had time to deliver the mail. Cliff was at the bar around the clock, every single day of the week. He also spent ample time with his mother, so between the bar and his “home life,” the window to actually pick up, sort, and deliver the mail must have been pretty small. Cliff had his share of transgressions, like falling for the young woman he trained and a bunch of minor but regular errors. (These screw-ups earned him a reputation among his colleagues, so much so that his name became synonymous with incompetence.) Yet the bosses never seemed to catch on. Maybe they were too busy drowning their sorrows at their own version of Cheers.

It’s tempting to think of Sue Sylvester as the most obviously fireable character on Glee. But it’s Will’s name that truly belongs on the whiteboard in the New Directions’ practice room. There’s little evidence that he’s done anything other than complicate the lives of both his students and fellow faculty. And it’s not just as a glee club coach that Will comes up short: A season-three episode showed this Spanish teacher actually taking Spanish lessons! A major turnover happened at the show when many of its main characters graduated; this would have been a perfect time to jettison Will and find a literal new direction for the glee club. But, no, after a brief stint in Washington, D.C., during which time he allowed a barely functioning Finn to take over day-to-day operations, he returned to have a mean-spirited sing-off with his son-surrogate.

Given the high turnover rate in the waitressing industry, it’s already a bit surprising that Ursula Buffay stayed employed at Riff’s—Paul and Jamie Buchman’s regular watering hole—for the better part of seven seasons of Mad About You. But it was her unceasing rudeness and general incompetence that makes that accomplishment truly staggering. With a long-standing history of either getting orders wrong or forgetting them altogether, Ursula’s immunity to termination can only be explained by her total lack of interest in gratuity. That, along with a general obliviousness to her own incompetence, was epitomized by her concerted effort to win Employee Of The Month. (Her slogan: “Ursula, Ursula, she’s our man! If she’s not Employee Of The Month, nobody can!”)

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.