RRR is the crowd-pleasingest thrill ride you didn’t know you had to see

The Telugu-language epic meshes cultural specificity with cinematic conventions from across the globe to create transcendent entertainment

There is an amazing film in limited release that you probably haven’t even heard of: RRR.

Full of colorful heroes, fiendish villains, staggering action sequences, dizzying dance numbers, and most of all, virtuous friendship, driven by feverish creativity and a sharp and unambiguous sense of pride for India’s people and their history, writer-director S. S. Rajamouli’s Telugu-language epic is quickly becoming the word-of-mouth sensation of the year. What Top Gun: Maverick brought to theaters upon its release in May—that joyful sense of escapism, cinematic derring-do and an expert manipulation of its audience’s heartstrings—RRR does just as well on an even larger scale, if that’s possible. And on the big screen or small, you simply must see it.

Not to be confused with Hindi-language standard bearer Bollywood, Telugu cinema, often called “Tollywood,” is a segment of Indian cinema created and produced in its namesake language. There are some similarities between Hindi and Telugu films, including vivid colors, ambitious musical numbers and operatic storytelling, but this film in particular shares almost as much in common with Hong Kong and American action films, and a worldwide interest in historical fiction. There are many reasons that Telugu films don’t often make this kind of impression of American audiences—starting with the fact that so few of them get international distribution. But particularly in the wake of Maverick’s needle-threading take on ‘80s nostalgia, RRR feels like exactly the kind of movie that audiences want, even need, right now.

Even without the fearless movie stardom of someone like Tom Cruise at the helm, its relentless capacity to please crowds, first in its initial release, then special-event screenings, and finally, as a part of Netflix’s streaming library (albeit in a different language), has catapulted it from appealing counterprogramming to a tremendous and seemingly indefatigable international sensation. While it’s undeniably a product of the film community, and industry, for which it was originally conceived, its growing and deserved success underscores the expansion of cinema as a platform for exploring different cultures and different traditions, as well as for the universality of a well-told story.

The story of enemies who become best friends

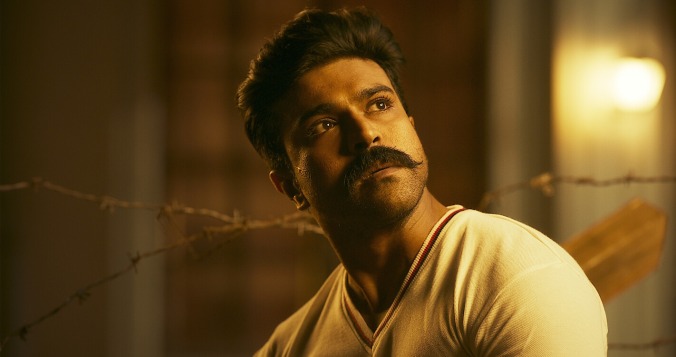

Set in 1920s India, the film stars N. T. Rama Rao Jr. as Bheem, a warrior and protector of the Gond tribe who comes to Delhi to rescue a young girl named Malli (Twinkle Sharma) after she is abducted by tyrannical British governor Scott Buxton (Ray Stevenson) and his wife Catherine (Alison Doody). When a regional official warns the Brits about Bheem’s mission, Buxton solicits a volunteer, Officer A. Rama Raju (Ram Charan), to apprehend him in exchange for a promotion in the ranks of the state police. Although Bheem disguises his identity, the two men cross paths while rescuing a young boy from a train crash, and they soon develop a powerful friendship without realizing that they’re actually adversaries.

While cinema both locally and worldwide engages in an ongoing referendum about representation, diversity, and the idea of exactly “who certain stories are for,” RRR exemplifies the opportunity that a moviegoer can and should have multiple access points to a film even if they’re foreign to the country or culture that created it. Suffice it to say that Rajamouli’s film doesn’t paint a particularly flattering portrait of Britain’s rule of India; Stevenson and Doody are callous and cruel. But RRR’s sense of nationalism should feel familiar to anyone who’s watched a rah-rah movie about America (or China or…), and its emphasis on the liberation of the Indian people could easily be translated—or transplanted—to more recognizable shores and situations. And yet the film takes its inspiration from the identities of two real-life Indian revolutionaries, Komaram Bheem and Alluri Sitarama Raju, and employs some broad historical details to give this opus a specificity and sense of urgency.

From familiar tropes to a cinematic triumph

What’s possibly even more important, however, is how it leverages a shared cinematic language—the conventions of action movies, musicals, and good old fashioned melodrama—to create an almost nonstop thrill ride that’s as exciting as it is (frequently) unbelievable. Fans of Hong Kong “heroic bloodshed” movies, and indeed the machinery of 1980s and ‘90s action films of America, will find much to enjoy (and read deeper meaning into) as Bheem and Rama become deeply emotionally invested in their mutual friendship; one could easily see Chow Yun-Fat in vintage The Killer or Hard Boiled mode as Bheem, a principled warrior betrayed by blind affection. Rajamouli’s screenplay creates these muscular, character-defining set pieces that introduce both of them, sets the stage for the sociopolitical and personal challenges they’ll face (both separately and together), and then finds endlessly inventive ways to push the story forward, if not always in an entirely linear fashion.

For example: RRR contains one of the best dance-offs I’ve ever seen on film. Bheem, innocent to the cultural practices of the country’s oppressors, gets a party invite to the governor’s palace from Jenny (Olivia Morris), Buxton’s compassionate niece, after they develop mutual crushes upon one another. When a self-aggrandizing English partygoer bullies Bheem with his mastery of Western dances, Rama intervenes by encouraging his pal with the song “Naatu Naatu” (which he kicks off with a blistering drum solo), and the two of them quickly take over the dancefloor as the rest of the guests try to follow their blinding footwork. Not only does the scene showcase Bheem and Rama’s dedication to one another, but it reinforces the characters’ cultural pride—and underscores the Brits as joyless, narcissistic fuddy-duddies.

Beyond the broader premise of a cop and a criminal developing a friendship or mutual respect for one another (in this case, with knowing who the other is), Rajamouli borrows lots of ideas that audiences have seen before, somehow without making them seem recycled or repetitive. Rama’s back story is suitably complicated—also born in a rural village, but driven to defend his people from within the prevailing power structure instead of outside, as Bheem does—and the film generates a real moral complexity from the idea of sympathizing, at least superficially, with an instrument of the state whose chief goal is to stop the correction of an indisputable injustice.

His arc vaguely resembles Django’s in Tarantino’s Django Unchained, or police cadet Chan Wing-Yan in Infernal Affairs (later brilliantly reimagined by Leonardo DiCaprio in The Departed) as the protector or freedom fighter who must act to deceive—to “intrigue,” as Django said—his oppressors into letting down their guard, and to embrace him as one of their own. The film showcases Rama as an indisputable bad ass—his introductory act is formidable and fearsome—but as more of the plot unspools, audiences begin to understand the moral quandary he faces, the better he does his job.

Using fiction to highlight true heroes

Rajamouli again weaves in some really terrific ideas about the lightning rods that these two men were, and are, for their country and culture—when Rama must reluctantly flog Bheem publicly to cower Delhi’s increasingly restless Indian population, the freedom fighter not only refuses to kneel in defeat, but sings a hymn that rouses the crowd to revolution. And at the same time, he treats them like twin Rambos (especially Rama) capable of enduring unimaginable torture—that is, when they are not dispensing beatings to dozens of opponents at a time. Bheem outwits a wolf and a tiger in his first scene, while Rama battles through a crowd of thousands to capture one rabble-rouser in his; and by the end, they’re pirouetting off of one another’s shoulders, wielding motorcycles like a policeman’s truncheon, and double-fisting machine guns as they defeat wave after wave of British soldiers. (Speaking of which, the film has quite possibly one of the most pro-gun attitudes of any film since the mid-1980s, so mileage may vary on that particular takeaway.)

Nevertheless, Rama Rao Jr. is wonderfully charming as the virtuous, slightly naïve Bheem, fierce and dedicated as a Gond protector navigating his way through a city under foreign, and hostile, control. Charan, meanwhile, is absolutely mesmerizing as Rama, not merely oozing with coiled sexuality (in his police costume, more than vaguely resembling one of the characters drawn by Tom of Finland), but brilliantly navigating the ideological compromises he has made—and continues to make—in order to achieve a singular goal. The action scenes practically leap off of the screen, and even at their most ridiculous (I mentioned that one of them swings a motorcycle, right?), Rajamouli maintains such a steady control of the film’s tone that nothing seems fully ridiculous, at least not within this heightened world.

Of course, American movies frequently abandon the pretense of believability, and audiences just as frequently balk. It’s hard to say exactly why this film works so well while much of Uncharted or Jurassic World: Dominion seems, well, absurd. But there’s something about it, even at its darkest moments, that’s so joyful, so charming, and so determined to keep you engaged that you simply cannot resist. And you won’t want to. What works, and enchants, is not a sense of exoticism, foreignness, or even exaggeration or hyperbole. What’s there isn’t to be enjoyed ironically or as an experience to gawk or giggle at. Rather, its specificity paves the way for a universal story, and universal sentiment. To get into RRR—and get on its wavelength—is less a challenge than a gift to the audience, and a reminder of the power of movies to transport, transform, entertain, and inspire, in any language.