Why The Exorcist is still the only great exorcism movie

And, no, it's not because of projectile puking, evil contact lenses, or yelling "The power of Christ compels you!"

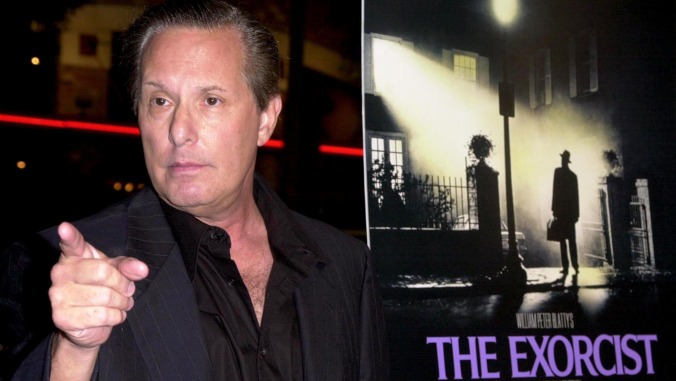

Nosferatu, the original vampire movie, set in motion the cinematic tropes of the subgenre, and since then many subsequent movies have done great things with its concepts, from Universal’s Dracula to Fright Night. John Carpenter’s Halloween crystallized everything we now associate with the slasher subgenre, which begat many more worthwhile films. But when it comes to exorcism movies, none have improved upon the only one worth talking about, and we don’t even have to say which one. 1973’s The Exorcist inspired many imitations, as well as multiple sequels and prequels, but none have eclipsed director William Friedkin’s classic. This month, The Exorcist: Believer will usher in the latest official entry, which director David Gordon Green hopes will kickstart a new trilogy. So it’s worth asking why nobody’s been able, in 50 years, to even come close to the quality and appeal of the original.

A little girl lost leads to a uniquely terrifying film

Most of the tropes The Exorcist set in motion are still common elements of the imitators. There’s a possessed girl (usually a girl, anyway) who wears monstrous contact lenses and speaks in distorted audio. There are at least two participants, usually male, in the exorcism—one a veteran, the other a rookie, like buddy cops. Peripheral figures die mysterious deaths, allowing for bonus scares, though it’s notable that The Exorcist itself keeps these completely off camera in order to make the final suicide more shocking. Characters yell “The power of Christ compels you!” or similar mantras. Some kind of ancient discovery or old mystery uncovered is usually key to saving the day.

But few, if any, of these hallmarks are essential to The Exorcist’s success and enduring appeal. The shock value of 12-year-old Regan (Linda Blair) undergoing graphic medical tests, not to mention the foul mouth and even fouler deeds that come later, is key to the horror. Most imitators, however, cast older victims to avoid the limited work hours of child actors, and the hassle of subbing in an older actress for just the explicit scenes. It doesn’t hurt that the potential sex appeal of an actress of legal age makes for a poster and project that are easier to sell to overseas buyers.

That aside, not only does The Exorcist keep two of its creepiest deaths totally offscreen, but it also eschews the kind of moody horror lighting we’ve come to expect from, say, The Conjuring series. When Regan’s head pivots backwards and she speaks in the voice of a man that her demon presumably murdered, it’s terrifying precisely because it’s happening in a realistic, naturally lit setting where such things simply don’t happen … and it cuts away before our eyes can analyze the magic trick too closely to see how it might be done. In so many knockoffs, similar effects use CG and darkness to create an obvious, telegraphed fright. The arrival scene of The Exorcist’s iconic Father Merrin (Max von Sydow), with all the fog, is about the only conventional horror-atmosphere shot in the original film.

A director committed to making evil feel real

A studio doesn’t hire the director of The French Connection to make a typical fright flick. William Friedkin commits from the first frame to making the world of the movie feel real—indeed, the area depicted as Iraq in the movie actually is Iraq, where filming took place with permission of the ruling Ba’ath party (of which, yes, Saddam Hussein was a member at the time). Scenes of Father Karras (Jason Miller) walking the dirty streets of New York City, and Chris McNeil (Ellen Burstyn) on a movie set at Georgetown University, all look like, and are, authentic locations full of grit, grime, and broad daylight.

Characters feel like they have lives beyond the action onscreen, and bits of characterization that don’t just further the plot. Whether it’s Chris’ director (Jack MacGowran) drunkenly obsessing over the German servant possibly being a Nazi, or Detective Kinderman’s (Lee J. Cobb’s) surprising cinephile side, there’s more to everyone than meets the eye. Young Regan doesn’t do anything scary until more than half an hour into the film—by then, the characters have all become compelling enough that any narrative featuring them would feel worth watching even without further demonic intervention. It helps that this all came from a novel, back when bestselling novels for adults were a thing—indeed, William Peter Blatty, adapting his own work, had to give the characters less to do and say than on the page, and it’s still more than similar screenplays can manage.

The Exorcist makes evil believable

It isn’t really Satan that scares you in The Exorcist—it’s the fact that believable, real people are threatened by forces they can’t handle. Like The Omen and other evil child movies of the ’70s, the film and the novel play on the fears of Baby Boomers who were just beginning to be parents and fearing they couldn’t control their kids in a newly permissive society. When we see shapely, perfectly teeth-whitened modern movie stars menaced by the digital devils of today, it can be fun, but it’s seldom relatable.

Most exorcism movies focus on the tropes, and not on the fact that a literate screenplay and onscreen reality matter much more. Then again, that’s true in most genres and subgenres. 2010’s The Last Exorcism, which used found footage to create the kind of real feel that studio films rarely aspire to anymore, did such a decent job creating a good story—with the exorcism itself being almost incidental—that it earned a sequel. It proved a rare outlier for a subject not reliant on any template. This goes for most horror subgenres, but particularly any movie that would aspire to ape The Exorcist: construct the environment and characters so effectively and immersively that people would watch them tell any sort of story. Then, by the time literal heads start spinning, the audiences’ might also do so figuratively, upon realizing someone else finally cracked the code.