Why the hell do we still care about Frasier Crane?

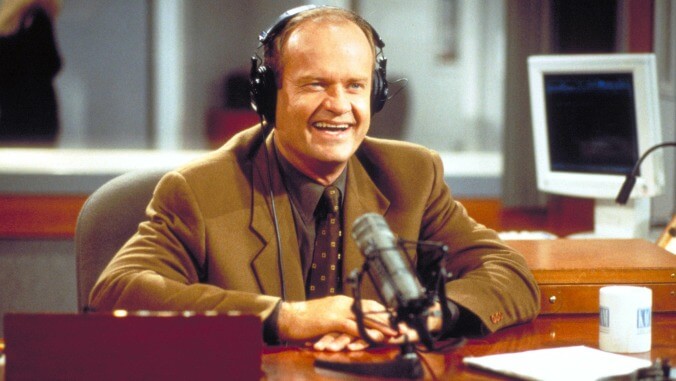

As Kelsey Grammer prepares to revive his most famous character for a third TV show, we have one question: Him?

Last month marked the 39th anniversary of the debut of Frasier Crane, a character whom Kelsey Grammer has now been playing, with some notable gaps, for more than half of his total time on Earth. This month, meanwhile, marks the end of one such lacuna, as Paramount+ releases the second TV show to bear the name Frasier and the third to feature Grammer as the character in a starring role. Returning to the world as a much older man, the new Frasier carries at least a whiff of the old one, with Dr. Crane arriving in a new-old town (his former Cheers stomping ground of Boston) to address a broken father-son relationship—this time, with his own adult son, Frederick (Jack Cutmore-Scott). Trailers for the show suggest that the series will follow at least some of the rhythms of the original, with a whole new generation of friends and family members lovingly having the crap annoyed out of them by one of TV’s most dedicated snobs.

Which raises the question: What, exactly, is it about this obnoxious, pretentious, condescending asshole that we all like so much? Paramount+ clearly believes there’s enough fan enthusiasm out in the ether to support Grammer’s long-held dreams of a reboot, and anecdotal evidence—the Frasier binge being a regular step on many an online addict’s streaming pilgrimage—suggests they might be right. Because the fact is that, even if Frasier himself is rarely its best part (something that doesn’t bode all that well for a reboot where he’s the only returning main character, by the by), Frasier remains a shockingly good example of the sitcom form. Strip off years of stereotyping and assumptions, complaints about the dog, Grammer’s own baggage, and more, and it’s still a show that resonates with people almost 20 years after its much-loved finale first aired.

So, let’s look back at a show that averaged more than three Emmy wins per season for a staggering 11 years, and which is apparently still so potent that it can bring tossed salads and scrambled eggs back to the people nearly two decades after the fact. Why this show? Why this guy? Why do Frasier, and Frasier, persist?

A matter of character

Sitcoms live and die on character. Jokes come and go, wacky situations are a dime a dozen, but character dynamics power everything. And the first Frasier established a doozy in its opening episode, “The Good Son,” which wastes little time in sketching out the complicated relationship between Frasier, his brother Niles (David Hyde Pierce), and his blue-collar, retired cop father, Martin (the late, and brilliant, John Mahoney). Things are initially so tense, and so ugly, between Frasier and his dad that a later retcon, meant to spackle over the fact that Frasier told his Cheers barmates that his dad was dead back during that show’s run, makes a surprising amount of sense: Given the friction between the pompous ass and the tough-as-nails detective in the show’s more grounded first season, is it any wonder that Frasier lied about being an orphan? The show would occasionally reduce the Frasier-Martin dynamic to a simpler Odd Couple vibe, but Mahoney, especially, could mine real feeling out of Martin’s bewilderment, and sometimes shame, at the way his son would act.

Niles, meanwhile, was a serendipitous masterstroke, having only been conceived of as a character after the show’s producers saw a headshot of Pierce, and noted his resemblance to Grammer. In building the character, series creators David Angell, Peter Casey, and David Lee created someone who could, essentially, out-Frasier Frasier: more neurotic, more snooty, and frequently more cutting, all in the hands of a performer who could handle anything you cared to throw at him. (It’s no shock that Pierce was nominated for the Emmy for Best Supporting Actor In A Comedy every single year Frasier was on the air, winning three times.) Playing friend, confidante, rival, wounded little brother, and ultimately serving as the show’s actual romantic lead, Pierce could deliver complicated multi-lingual wordplay one moment, and one of TV’s all-time-great physical comedy scenes the next.

Really, though, all of the main Frasier characters share a key trait: an ability to out-maneuver their leading man. Jane Leeves’ housekeeper/physical therapist Daphne could cheerfully blow off her boss’ pompous rage. Peri Gilpin’s Roz, a force of nature and a union woman, got the best of him almost constantly. None of which is to discount Grammer’s own good work, inhabiting this version of Frasier (more snobby and pompous than the one he played on Cheers, but still recognizably the same guy) with total commitment. But all involved seemed to grasp that the joys of Frasier came in taking a man who considered himself the urbane, composed master of the universe, and then slamming him, full-force, into characters with no interest in taking his shit.

High-brow slapstick at its finest

That same approach also applied to the show’s comedy plotting, which was often deliberately throwback in style in its efforts to turn the screws. (We can roll our eyes at many of the tropes of classic bedroom farce, but still look to season five’s “The Ski Lodge” as a near-perfect example of the form, with misunderstandings, swapping rooms, and hornily slammed doors in abundance.) When Frasier was really cooking, few shows could match its knack for ambition, tension, or comedic escalation, with Grammer as a straight man constantly on the verge of going nuts.

We mean that “cooking” bit literally, too: Look no further than second season masterpiece “The Innkeepers” for an obvious example of why Frasier still lands nearly 30 years after its initial airdate. The episode, which sees the Crane boys trying to Big Night it up by running their own restaurant, begins with a steady stream of setbacks, as they lose their chef and waitstaff, press-ganging Niles, Daphne, and Roz into service in their stead. But it’s only when an entire table of food critics (led by Frasier’s workplace nemesis Gil, the delightfully smug Edward Hibbert) arrives that the episode truly unleashes, showcasing a cast-wide talent for slapstick that belies the show’s ostensibly high-brow nature. It’s hard to highlight one moment of the rising chaos as the most laugh-out-loud funny—although it’s probably the bit where Jane Leeves murders an eel—but the sheer energy of the four-minute sequence is infectious, manic, and undeniable. (You can see Grammer just barely keep it together when Gilpin walks back into the kitchen after a disastrous incident with cherries jubilee.) Frasier didn’t go to this particular well too often—pulling out the stops just a few times per season. But anyone who only remembers the show for witty repartee in coffee shops should refresh themselves on all the ways it paid homage to the high-energy, incredibly fast-paced classics, Frasier himself never far from a quick dose of comedic karma.

Psychological strengths

Which isn’t to discount that java-based dialogue, either. As a show with two psychiatrists in its main cast, Frasier was more willing than most sitcoms to get introspective, especially in its early going—and especially in its first few season finales, several of which see Frasier contemplating whether he’s actually happy with his new life in Seattle.

The most memorable of these, probably, is the first: season-one ender “My Coffee With Niles,” which serves as a deliberate bookend to “The Good Son.” (At last: the saga of Niles’ battle with his gardener over a potential Zen garden concludes!) Basically a bottle episode (the outdoor set for the brothers’ regular haunt, Café Nervosa, appears to be new for the installment), it’s an episode-length meditation on the meaning of happiness, bringing all of the show’s main characters into the orbit of its ongoing conversation between Niles and Frasier. It also captures so much of what works about the series’ quieter side, Pierce and Grammer trading barbs and moments of sincerity, Mahoney giving bluster and warmth. The show would return to these themes only periodically across its run, notably with season eight’s “Frasier’s Edge,” which ends with some of Grammer’s best acting in the series, and then its celebrated series finale. This occasional melancholy (which can trace its origins, like Frasier’s, back to Cheers) is just one element of the show’s success. But it’s a key one, giving a counterweight to those moments when it goes completely, joyfully bonkers. (Looking at you, “Theme To The Frasier Crane Show.”)

What does all this mean for 2023's Frasier?

A show like Frasier is a lot to live up to. The original was created by some of the best sitcom writers of a generation, staffed with some of the best sitcom actors of a generation, buried in awards, etc. Judging the new series, strictly on those merits, is likely to be a fool’s errand. But at the very least, this framework does give us an understanding of what “Frasier” actually was, beyond the very basic, kneejerk description of “Kelsey Grammer acts like a prick about couches.” For fans of the old show, at least, the new Frasier can’t help but be judged by how it lives up to those strengths—the heights of intense energy, the deliberate emotional lows, the perfectly composed character dynamics set like wonderful spinning tops around the lead. It’s a road map to the best places this show got to, as it meandered (sometimes with less focus than others) across 11 seasons on the air.

Or, hey: Maybe not. Frasier wasn’t all that much like Cheers, with everybody involved doing their best to break out of a highly successful mold. Reinvention is Frasier Crane’s one true constant. Maybe the new series can pull that trick off, too. It worked once, after all.