Why Unwound is the best band of the ’90s

There they sat—one young woman and two young men, their clothes drab and their hair unkempt—huddled together as if for warmth. All around them, people were talking, joking, laughing. Not these three. They clutched half-eaten burritos like starving children, whispering among themselves.

I walked over. I said something.

They stopped and stared at me. Their faces were wary and bewildered, as if they were zoo animals and I had rattled the bars of their cage.

“Thanks,” said one of the young men. I never knew someone could mumble and snarl in one syllable. There was no gratitude in the word—only a sardonic loathing that seemed aimed at everything and everyone in the room, maybe even the young man who said it. Then he turned back to his two comrades and resumed whispering. I stood there for a few seconds before I realized I had been dismissed.

All I’d said was, “I really love your band.”

The band was Unwound. The year was 1995. My own band, a little outfit from Denver you’ve never heard of, had scored a coup: opening for Pegboy at The Fox Theatre in Boulder. Pegboy was one of my favorite bands at the time, a gruff, no-nonsense punk group that wore its heart on its rolled-up sleeve. Unwound, strangely, had also been placed on the bill. It must have been a case of booking-agent expediency; Chicago’s Pegboy and Tumwater, Washington’s Unwound were not the types of bands that would have known each other, let alone toured together. Backstage that night, that disconnect was evident at the pre-show gathering of band members. Hearty and outgoing, the dudes from Pegboy immediately struck up a boisterous conversation with my bandmates and me. Sickly and withdrawn, the members of Unwound sulked in the corner like outsiders at their own party.

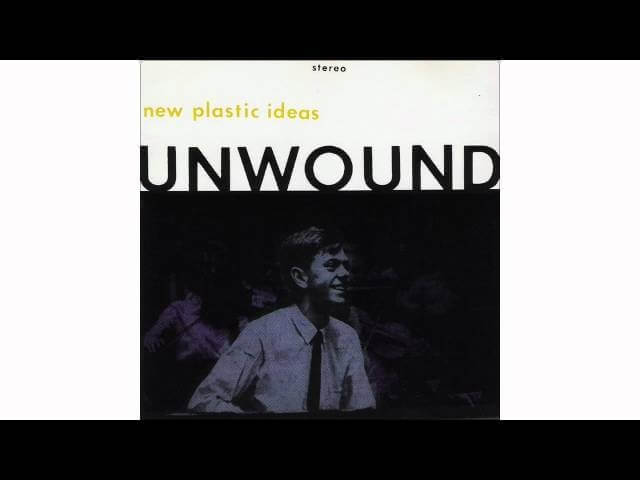

As much as I loved Pegboy back then, I loved Unwound more. I’d bought the band’s debut album, Fake Train, when it came out in 1993, and 1994’s New Plastic Ideas topped it. But Unwound’s music was nothing like Pegboy’s. Instead of surging power chords and song titles like “My Youth” and “Believe,” Unwound made angular noises and wrote song titles like “Lucky Acid” and “Abstraktions.” On stage that night, the contrast between these two approaches to ’90s rock became more striking. During Pegboy’s set, the crowd sang and sweated. If anyone was sweating during Unwound’s moody, mathy spasms of feedback-shrouded mystique, it was out of nervousness. Pegboy was a plate of meat and potatoes; Unwound was one of those crumbly cheeses that’s pungent, complex, and laced with mold.

Accordingly, Unwound got even better with age. Each step in the trio’s evolution is daring and distinct, yet oddly logical. And it’s one of the rare groups whose final album—in this case, 2001’s sprawling, spectral Leaves Turn Inside You, which for all intents and purposes is Unwound’s Kid A—is its best. Even if there’s no credence to the theory that the ’90s didn’t truly end until September 11, 2001—which would render Leaves Turn Inside You a ’90s album in spirit if not in fact, and maybe even the decade's greatest swan song—Unwound’s string of six albums released between 1993 and 1998 would be enough to give the group legitimate claim as one of the best bands of the ’90s.

For me, it’s no contest: Unwound is the best band of the ’90s. Not just because of how prolific, consistent, and uncompromising it was, but because of how perfectly Unwound nested in a unique space betweenn some of the most vital forms of music that decade: punk, post-rock, indie rock, post-hardcore, slow-core, and experimental noise. That jumble of subgenres doesn’t say much; in fact, it falls far short of what Unwound truly synthesized and stood for. Unwound stood for Unwound. But in a decade where most bands were either stridently earnest or stridently ironic, Unwound wasn’t stridently anything. It was only itself. In one sense Unwound was the quietest band of the ’90s, skulking around like a nerdy terror cell. In another sense it was the loudest, sculpting raw noise into contorted visions of inner turmoil and frustration.

That’s not to say Unwound lacked musical influences. In particular, the shadows of Sonic Youth and Fugazi loom large over Unwound’s mix of dissonance and rhythm. But where Sonic Youth was extravagant, Unwound was austere. And where Fugazi was militant, Unwound was ambiguous. That’s partly the reason why I think Unwound’s music has stood the test of time more solidly than either Sonic Youth or Fugazi, as great as both bands are. Unwound could bust into an anthemic chorus—as it does, for instance, on “Lady Elect,” one of the standout tracks from 1996’s Repetition—but even then it’s eerie and subtle, smuggled in sideways in spite of itself. At a time when the alt-rock formula called for quiet verses and loud choruses, Unwound employed dynamics in a way that was organic, idiosyncratic, and unsettling. The buildups and comedowns are still there, but they’re tied to the ebb-and-flow of far more volatile brain chemistries.

Unwound also influenced untold numbers of bands. Modest Mouse, who sometimes played with Unwound in the mid-’90s, recently took Survival Knife, the new band with Unwound vocalist Justin Trosper and original Unwound drummer Brandt Sandeno, on tour. Corin Tucker of Sleater-Kinney—a group that came up in the same ’90s underground scene that Unwound helped define—currently counts longtime Unwound drummer Sara Lund as a member of her Corin Tucker Band. And then there’s Unwound’s similarity to another Pacific Northwest luminary of the ’90s: Nirvana. At first glance, the two groups don’t seem related at all. But there’s a layer of grunge grime on Unwound’s early records, conceived at the same time Nirvana was kicking around in Unwound’s backyard—and Trosper has admitted the inspiration. That might have gone both ways, though; listening to the strangled, wiry riffage of In Utero, it’s not hard to imagine it as a companion piece to Fake Train.

But Unwound doesn’t feel like just another drop in the continuum. The band existed apart from, yet roughly parallel to, the primary streams of ’90s rock—avatars of an alternate history of the decade, one where pop didn’t win again, as it had after every other counterculture movement. To Unwound, the ideals ushered in at the start of the alternative revolution actually mattered and were honored. There are hooks galore in Unwound songs, but the listener has to work for them. And they’re more dimensional, emotional, and rewarding because of it.

I didn’t have the hindsight to understand any of this at that Fox show in 1995. Mostly I felt that Unwound was a bunch of dicks—not that my social skills were particularly developed at the time. I don’t think Unwound is the best band of the ’90s because they were kind of jerks to me one night in 1995, and I’m some kind of glutton for abuse. But I’d be lying if I said that my experience that night didn’t factor into it. The ’90s were all about manufactured—or at least manicuring—angst. It was about putting a friendly face on miserableness or weirdness or sociopolitical consciousness and selling it. It was about riding the fake train. Unwound wanted nothing to do with that. The band didn’t sing sanctimonious songs about how it didn’t merchandise itself in the way, say, Fugazi did—it simply conducted itself as if that weren’t an option.

And maybe it wasn’t an option. As excellent, influential, important, and even emblematic as Unwound was, it was never huge. A series of exhaustive Unwound reissues will begin coming out soon, and they may change that, or they may not. Timelessness is often the result of staying just under the radar enough—just beyond the zeitgeist enough—to embody an era while perversely defying it. Unwound did that, in mumbles and snarls, an outsider at its own party.