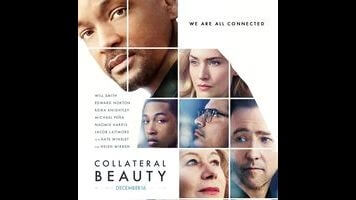

Will Smith goes glum for the twisty treacle of Collateral Beauty

Collateral Beauty is one of those cloying movies about learning to take the good with the bad that feels like it was made by aliens with little grasp of human life. (Presumably from the Andromeda galaxy, whence come the dreaded dramedies.) In a performance that rarely requires him to move the muscles of his face, Will Smith stars as Howard Inlet, a former advertising guru living in grief some years after the death of his daughter. Still the majority owner of a Manhattan ad agency, Howard shows up to the office every day only to build intricate structures out of dominoes, presumably symbolic of something. His evenings are occupied with the sort of mourning activities that are the hallmarks of a film with no sense of interiority: alone time in an unfurnished apartment, angry bicycling (to which the film devotes several montages set to today’s faux-folk equivalent of the anodyne pop-rock ballad), the occasional hour spent lingering outside the window of a support group for grieving parents.

With the company in dire financial straits, Howard’s minority partners Whit (Edward Norton), Claire (Kate Winslet), and Simon (Michael Peña) conspire to wrest control by hiring three struggling actors (Helen Mirren, Keira Knightley, and Jacob Latimore) to randomly sneak up on him on the subway or while he’s eating and pretend to be personifications of death, love, and time while an unscrupulous private eye secretly records their interactions and doctors the footage so that it looks like Howard is talking to himself. (Yes, this is really the premise.) A reader might presume that this high-concept ensemble gaslighting would result in farce and disaster and not, say, valuable life lessons and a triple twist ending in the Sea Of Trees vein. But what this reader doesn’t realize is that it is really the minority partners who need to have sophomorically written conversations with abstract concepts while standing in the public way.

Over-sharing divorcé Whit has lost the respect of his daughter because he cheated on his ex-wife; high-strung Claire wants to have a baby because she is a woman; shy Simon is actually, seriously terminally ill. And perhaps at this point, this reader—this theoretical reader—might guess that the life-changing actor spirit guides were in fact hired by Howard, and it is the partners who are being gaslit into a better understanding of themselves. Collateral Beauty isn’t that clever. The script, by Allan Loeb (The Switch, Here Comes The Boom), seems like satire at first, with its offhand references to previous failed interventions in Howard’s life, like an ayahuasca shaman who was flown from Peru at great expense. But it is lethally sincere when it comes to bathos and psychobabble.

Does Collateral Beauty feature an out-of-nowhere monologue in which a side character explains the invented concept of “collateral beauty,” but not well enough for the audience to understand why the movie needs a term for it? Of course it does. Having somehow amassed an embarrassingly overqualified cast, director David Frankel (The Devil Wears Prada, Marley & Me) embraces the schematic structure: Howard gets two scenes with each of the out-of-work actors (introduction, confrontation), each of the actors is paired up with one of Howard’s partners, and so on and so forth. The only advantage of this is that it makes it very easy to measure how much time the film has left. And it’s not even very long.