Willem Dafoe plays Van Gogh, a man 25 years his junior, in the reductive biopic At Eternity’s Gate

For the first time since he turned to filmmaking with 1996’s Basquiat, celebrated painter Julian Schnabel (whose other movies include Before Night Falls and The Diving Bell And The Butterfly) has paid tribute to a fellow artist. Unlike Jean-Michel Basquiat, however, Schnabel’s latest subject isn’t exactly someone whose story had previously been neglected on screen. Directors ranging from Vincente Minnelli (Lust For Life) to Robert Altman (Vincent & Theo) have explored Vincent van Gogh’s short, torturous life in considerable detail. Just last year, we saw Loving Vincent, which is animated via a series of oil paintings in van Gogh’s style. Does At Eternity’s Gate have anything new or innovative to share about perhaps the most comprehensively documented painter who’s ever lived? Does the world need another van Gogh biopic?

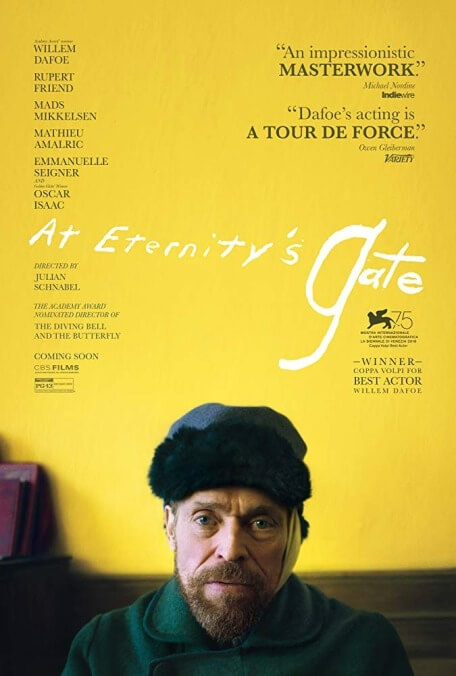

Not really. Schnabel has admittedly cast a great actor in the role, even if it’s slightly ridiculous to have Willem Dafoe, who’s 63, play a man who died at age 37. (Van Gogh does at least look older than that in his many self-portraits.) And he’s chosen to focus almost entirely on the last few years of van Gogh’s life, which he spent in France, furiously creating one masterpiece after another—over 200 paintings, plus half as many drawings—despite spending considerable time in the hospital and an asylum. The infamous ear-cutting took place during this period, as did heated discussions about the nature of art with fellow genius Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac). Mostly, though, Schnabel wants to convey the beatific mania that he imagines drove van Gogh. There’s even a lengthy scene in which Vincent, at the asylum, talks with a priest (Mads Mikkelsen) who despises his work, inspiring an extended comparison of creativity and religious faith.

Schnabel’s screenplay (cowritten with Louise Kugelberg, who has no previous credits of any kind, and the great Jean-Claude Carrière, who has a zillion, including The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie and The Unbearable Lightness Of Being) is heavy on this sort of philosophical dialogue, which often makes van Gogh and Gauguin sound as if they’re extemporizing the post-Impressionist equivalent of Hitchcock/Truffaut. It doesn’t help, verisimilitude-wise, that the film’s use of language makes little sense: Vincent speaks French to the villagers in Arles and Auvers-sur-Oise, but converses in English with everyone else. Van Gogh apparently did in fact speak English, but it’s unlikely that he’d have done so with Gauguin, or with his brother, Theo (Rupert Friend), or with Mikkelsen’s presumably French priest. English clearly just stands in for either French or Dutch whenever subtitles might become too laborious. Movies cheat like this all the time, of course, but Schnabel’s weird half-measure only serves to create a recurrent feeling of phoniness. (He also frequently repeats lines of dialogue seconds later, layered in freaky voice-over, which is perhaps intended to suggest van Gogh’s psychic distress but comes across as an empty affectation.)

At Eternity’s Gate is at its best when silent, viewers studying Dafoe’s (too-) weathered face and watching van Gogh trudge through the French countryside with his easel, searching for just the right light. The film’s most inspired moment sees Schnabel abruptly shift to black-and-white as Vincent works; the absence of color, combined with shooting the canvas at an oblique angle, emphasizes the canvas’ stunning texture—the way that van Gogh, as Gauguin notes aloud (in typically expository fashion), often seems to be sculpting as much as he is painting. Unfortunately, Schnabel also appears to have bought into the fashionable notion that van Gogh experienced xanthopsia (a yellow bias in the field of vision), induced by some medical disorder. Throughout the film, but without any consistency, we get shots from Vincent’s point of view, to which Schnabel applies a severely yellow filter; he also blurs the bottom third of the frame, though it’s not clear how that visual distortion manifests itself in van Gogh’s paintings. Attempting to “explain” an artist’s striking use of color or perspective via some hypothesized illness or physical anomaly belittles creativity, reducing something mysterious and profound to what’s essentially a transcription error. One would think that Schnabel, of all filmmakers, would know better, but perhaps he just needed some new angle on this overly familiar figure.