No one with working eyes or exposed extremities would ever confuse Wyoming in the winter for East Texas or the border between the U.S. and Mexico. All the same, the sweltering Southwest battlegrounds of Hell Or High Water and Sicario aren’t so different from the remote, mountainous, and dangerously frigid Indian reservation where most of Wind River takes place. Taylor Sheridan, the one-time Sons Of Anarchy cast member who wrote all three movies, has trekked north for his first gig behind the camera, but his interests haven’t changed with the climate; they continue to trend toward lawmen in cowboy hats chasing criminals across the impoverished moral gray areas of the American backcountry. Colder temperatures aside, we’re still very much in Sheridan Land, where the alliances are generally uneasy, the dialogue crackles as loudly as the gunfire, and ancient cultures disappear quietly into the dust (or, in this case, snow).

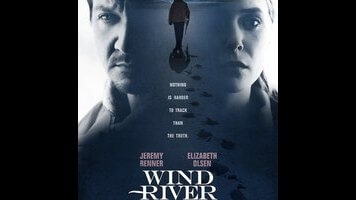

Everything starts, as is often the case in detective yarns, with a body. It belongs to Natalie, a Native American teenager who flees barefoot for her life through the snow in the opening scene, before collapsing dead in the dead of night, lungs choked with frozen blood. Cory Lambert (Jeremy Renner), an agent of the Fish And Wildlife Service, stumbles upon her while searching for a highly symbolic family of mountain lions preying on local livestock. An expert tracker and marksman (his aim rivals that of Renner’s sharpshooting Hawkeye), Lambert thinks of himself simply as a hunter, and now he has serious game in his crosshairs. Although he knew Natalie, his real motivations for getting involved run deeper. (“The only thing Indian about you is your ex-wife and the daughter you couldn’t protect,” someone very unwisely tells him.) This is Sheridan’s way of personalizing the mystery, of giving his hero a stake in the hunt, but the anguished backstory mainly puts Renner in the uncomfortable position of delivering long, grave speeches about grief. He’s better when playing the character flinty, like the quintessential cowboy of the Cowboy State.

Lambert ends up paired off with rookie FBI agent Jane Banner (Renner’s Avengers teammate Elizabeth Olsen). Sicario caught some heat for introducing a headstrong heroine—Emily Blunt’s by-the-book fed, dragged into a hellish war of attrition—only to make her a powerless spectator. But that was arguably the whole point of the movie, which squashed the character’s agency to underline the futility of taking a moral stand within a corrupt system. There’s no such excuse for the way Wind River constantly undermines Olsen’s superficially similar Banner. From the moment she arrives at the scene, she’s in entirely over her head, and Sheridan keeps finding new ways to demonstrate it—laying bare her insensitivity during an interview with the bereaved parents, having suspects get the jump on her several times, even poking fun at her choice of underwear. Mostly, the character exists as a foil; try as Olsen might to play Banner no-nonsense capable, she effectively functions as the clueless outsider, messing up to accentuate Renner’s macho insider know-how.

Because the body is discovered on federal land, Lambert and the local authorities have to wait for the FBI to arrive before they can investigate; because Natalie died of the cold, and not from injuries sustained during her apparent rape and assault, the coroner can’t call it a murder, meaning the case may end up falling on the grossly understaffed tribal police. Questions of protocol and jurisdiction fascinate Sheridan, and they help distinguish his film from the usual small-town murder mystery. So, too, does the setting. What emotional kick Wind River possesses has less to do with Lambert’s battle with the ache of his loss and more with a lament for the isolated residents of the reservation, sharply embodied by a supporting cast of Native American actors, including Graham Greene as the matter-of-fact sheriff and Hell Or High Water’s Gil Birmingham as a father going through the worst crucible a parent can endure. (Birmingham is superb enough in the role to make one wonder if the film picked the wrong protagonist, especially given the cultural sympathies it announces.)

Sheridan, it must be said, doesn’t yet have the muscular action chops of Denis Villeneuve or David Mackenzie, the directors who tackled his other scripts; the gun fights are a little sloppier, the overhead shots of unforgiving landscapes a little less foreboding and/or majestic. But his plotting remains mean, lean, and economical, as the film rallies for a climax that lays out a tense confrontation while simultaneously solving, through harrowing flashback, its central mystery. Some opening text vaguely insists that all of this is “inspired by true events.” Honestly, the less true that is, the better, given the horror of what happens. Wind River may be steeped in the real agony of American experience, of the country’s most marginalized, but it still feels like a return to a place more mythic: the sprawling outlaw frontier of Taylor Sheridan’s imagination.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)