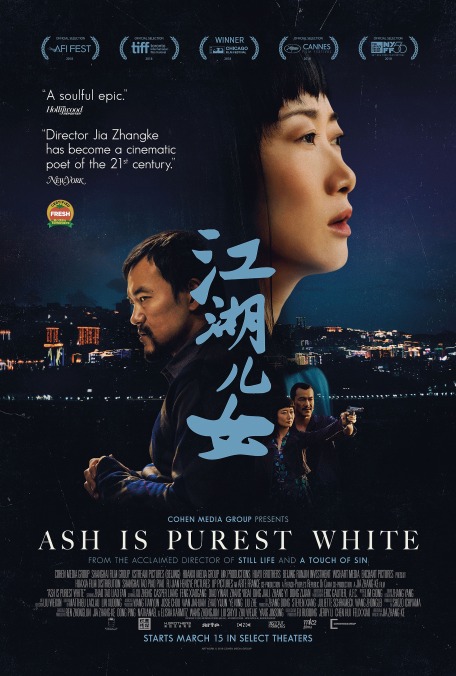

Just shy of an hour into his new movie, Ash Is Purest White, the great Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke offers up a truly ingenious, discombobulating callback. The setting, momentarily, is 2006. On the deck of a ferry approaching the banks of the Yangtze River, Jia’s longtime muse and spouse, Zhao Tao, surveys the scenery. It’s a mirror image of a moment from the director’s monumental Still Life, which also took place in 2006, the year it was shot. Except that the scenery itself doesn’t look the way it did back then. Fengjie, the rural area where that earlier film was set, is gone—completely submerged, as Still Life warned it would be, by the rising water levels caused by the Three Gorges Dam, and effectively replaced with a modern city. After more than two decades studying the changing face of China, Jia has found—in this eerie anachronism—the perfect metaphor for a country perpetually in transition. Is there a more potent way to communicate the ongoing transformation of a place than to let the current, contemporary version of it “play” the older one?

It’s not a moment, admittedly, that will land for everyone. Because to appreciate what Jia is doing, you need at least some familiarity with the particular time and place he’s depicting. That’s true, of course, of most of the director’s films—the state-of-the-nation addresses he’s been delivering for 20 years now, roughly beginning with his international breakthrough, Platform (2000), which followed a troupe of young performers from the end of the 1970s until the beginning of the 1990s. Ash Is Purest White, an ambitious but intimate gangster melodrama, covers a similarly wide time frame, beginning around the turn of the new millennium—which is to say, not long after the release of Platform—and ending in basically the present. Here, though, there’s an extra layer of context, as Jia isn’t just racing through two decades of rapid cultural change. He’s also offering a glancing tour of his own filmography, returning to themes and locations from past work. It’s a movie that will resonate with diehards, even as it carves out its own offbeat stylistic identity, its own niche.

As in his last film, the uncharacteristically clumsy Mountains May Depart, Jia has trifurcated his narrative, each distinct segment separated by a significant block of time. One might initially confuse the first for an outright remake, unfolding as it does in the same then and there as his Unknown Pleasures: the Datong nightclubs of once-contemporary 2001, where disaffected youth obsess over the Western pop culture that’s infiltrated their lives. The déjà vu factor peaks with our first sight of the aforementioned Zhao, bangs cropped exactly as they were in the earlier film. Is this Qiao the same Qiao we met in Unknown Pleasures? Spiritually yes, technically no. Here she’s a gangster’s moll, deeply infatuated with her slick mobster boyfriend, Bin (Liao Fan), who holds court over the local dance club, settling disputes among his hotheaded crew.

There’s a certain glamour to Qiao and Bin’s nocturnal lifestyle, dancing all night to “YMCA.” But the jianghu, the loose crime syndicate to which they belong, is just another old-world industry on the wane in post-millennial China. Rival gangs have begun encroaching on their turf—a development that dovetails with the ongoing flow of new financial interests into Datong, be they the redevelopment deal that’s consuming a local mine (“We must fight the capitalists until the end,” Qiao’s father impotently bellows into a microphone) or the influx of American and European trends, like disco and ballroom dancing. Something has to give, and it does when Qiao intervenes during a brawl with another gang, saving Bin’s life with his illegal handgun, then taking the fall for possession. She gets five years in prison. When her sentence is up, she goes looking for her lost love, taking a boat to a familiar place made unfamiliar through “progress.”

This plot development, complete with time jump, allows Jia to pivot from one milestone of his career to another, trading the Datong of 2001 for the Fengjie of 2006, connecting the aimless youth of Unknown Pleasures to the estranged, unmoored lovers of Still Life. Spanning most of the time Jia’s been making movies, Ash Is Purest White feels like a moment of retrospection, cultural and creative. It’s not a retread, though, even when explicitly echoing past triumphs. There was a time when the director clung to a monolithic austerity, a gospel of long takes, wide shots, imposing landscapes, and almost glacial camera moves. But his movies have gotten looser, funkier, and more commercial over the past few years. Working with Éric Gautier, Olivier Assayas’ regular cinematographer, Jia pushes that further in Ash Is Purest White, toying with tone and genre. There’s a spectacularly shot Hong Kong-style brawl in the first segment and a pocket of screwball comedy in the second, as Qiao—back on the outside after half a decade behind bars—capitalizes on the lecherous stupidity of the men she encounters. Jia even works in a little sci-fi, the synth-driven score confusing the present with the future, though the appearance of a certain unidentified flying object is straight from his cinematic past.

It all comes full circle in the final segment, set in some melancholy approximation of the here and now. Is there a larger devotion, a kind of wounded national pride, in Qiao’s undying loyalty to Bin, in the way she pushes onward through an uncertain new era, pining for something that’s disappeared as surely as Fengjie has? Ash Is Purest White, like most of Jia’s work, conflates the individual and the state, the fate of its characters with that of China itself. But it’s Zhao—the reliable constant of this director’s estimable body of work, the human face of his grand, career-spanning project—that grounds all that in a dramatic reality. Abstractly reprising old roles, she reverse-engineers an emotional continuity (an arc, even) between them, and you realize how much these films belong to her as much as they do to Jia. Perhaps the metaphor of that remarkable mid-film reveal extends to Zhao’s performance, too: As surely as any landscape reshaped by rising tides, she shows us the sea change of the new century.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)