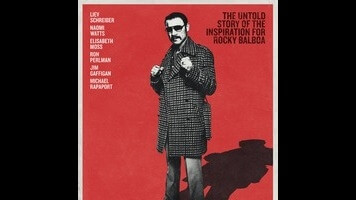

There really was a Rocky Balboa. Well, sort of. His name was Chuck Wepner, and when he wasn’t throwing punches in the ring, he sold liquor in New Jersey. In the mid-’70s, the “Bayonne Bleeder,” so nick-named for his habit of absorbing a lot of blows to the face, was at the right weight at the right time to score an unlikely title fight against the one and only Muhammad Ali—a match that inspired a young Sylvester Stallone, watching on his television from home, to mine the basic details of the boxer’s story for his own breakout star vehicle. Chuck, the new biopic about the real Wepner, dramatizes some of those same details, with much more fidelity to the facts. At the same time, it also acknowledges how Wepner’s life was changed by there being a movie (again, sort of) about his life. Imagine, if you can, a shadow remake of Rocky that’s also explicitly about Rocky.

Maybe that makes the movie sound more interesting, in a house-of-mirrors way, than it really is. In truth, Chuck doesn’t stray far from from the underdog, just-a-lug-from-the-streets redemption arc that Rocky itself helped eternally popularize. Philippe Falardeau, the Québécois director of Monsieur Lazhar and The Good Lie, gives the project a diet-Scorsese snap, setting an eventful decade in the New Jersey heavyweight’s life to wall-to-wall ’70s staples. The model is less Raging Bull than Goodfellas: Beginning with a rock-bottom stunt bout that pitted a retired Wepner (Liev Schreiber) against an actual bear, the film flashes back to trace his waxing and waning fortunes. Throughout, Schreiber does his best voice-over Henry Hill imitation; “As far back as I can remember, I could take a punch,” the narration stops just just short of proclaiming during a flashback to the fisticuffs of Wepner’s youth.

The big moment of the fighter’s career was his match with Ali, and one could imagine a version of the movie that climaxed right there in the ring, with Wepner surviving 15 pummeling rounds, once even knocking down his world-famous opponent, before The People’s Champion put him out of his misery. Falardeau derives some rousing mid-film spectacle from the showdown, but overall, the highs get less play than the lows: a gimmicky farce of a match against Andre The Giant in Shea Stadium; a jail stint; the failure of Wepner’s marriage. (As his long-suffering first wife, Elisabeth Moss gets one great scene, a public dressing-down of her philandering husband that she delivers with a righteous, controlled fury more powerful than any uppercut.) Chuck understands that Wepner wasn’t one of the greats, that he was better at receiving beatdowns than meting them out. The movie is more interested in him as a lovable loser, a working-class palooka who stumbled briefly into the spotlight, and Schreiber—bulked up, mustachioed, having a grand time—leans enjoyably into his hangdog mediocrity.

Eventually, Rocky rockets Wepner into a new sphere of celebrity, one that proves difficult for him to capitalize on. (If you have to constantly explain how you’re the guy that Rocky is based on, it’s probably not going to do wonders for your career.) From here, Chuck flirts with wading into the art-imitates-life-imitates-art implications of its story, from Wepner’s love of Requiem For A Heavyweight to a textually loaded scene of Schreiber-as-Wepner watching Rocky in a crowded movie theater. But the film sheepishly sidesteps less flattering details, like the fact that Stallone (played here by Morgan Spector) denied for a while that Balboa was based on anyone, before quietly settling a lawsuit brought against him by the fighter. Maybe neither party wanted that in the film. Or maybe it just competed with Chuck’s more crowd-pleasing arc, in which the down-and-out contender finds his own Adrian (Naomi Watts, who’s married to Schreiber in real life) and learns that family is more valuable than fame. “Sometimes life really is like a movie,” this Wepner eventually concludes. “Sometimes it’s better.” As Chuck reminds, it’s usually more interesting, too.