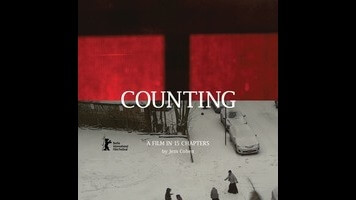

It doesn’t feel quite right to call Jem Cohen’s Counting an essay film. It’s more like a collection of snapshots taken out the window of a moving train by a backpacking student abroad who’s too distracted by the scenery to focus on the heavy textbook in his lap. That’s not a criticism, by the way. Shot over several years in cities from New York to Moscow to Porto, and divided into 15 chapters of wildly varying length, Counting finds the director of the charming, critically acclaimed fiction-doc hybrid Museum Hours practicing the sort of impressionistic, globe-trotting cine-journalism pioneered and perfected by Chris Marker—a debt that the director acknowledges explicitly in the final sequence. (Cats also abound throughout.) But where Marker’s great works A Grin Without A Cat and Sans Soleil were delivery devices for their maker’s eloquent voice-over assessments of history, politics, and culture, Counting eschews narration. Aside from a few judiciously chosen quotes, it seeks to speak entirely through images.

Most of what Cohen is shooting here is far from spectacular: city streets and museum exhibits, and views through the windows of moving vehicles. It’s a liberated style, and yet certain compositions and editing choices are sharply pointed; a section entitled “Three-Letter Words” overlays shots of people talking on cell phones with the audio of congressional debates on government surveillance. It’s an unsubtle juxtaposition that’s complicated by the essentially voyeuristic nature of Counting itself; even as Cohen needles the NSA, he acts in his capacity as a filmmaker as a kind of surreptitious spy. There’s a fine line between curiosity and nosiness, and it’s to Cohen’s credit that he never seems to be simply rubbernecking, even when the shooting takes him into exotic spaces like the Kremlin (the shifting nature of American-Russian relations over the last half-century is a structuring motif). He also manages to make urban America strange and exhilarating simply by training his camera on public spaces and observing how they’re used and occupied, including by protestors (another connection to Marker, who was never friskier nor more focused than when infiltrating public demonstrations).

The appeal of Cohen’s glancing approach is that the viewer doesn’t feel nudged toward any conclusions, or even all that compelled to pay attention on a shot-by-shot basis; it’s possible that one person’s favorite sequence will fly over the head—or under the radar—of another. The drawback is that, in the absence of any grand thesis statement or rigorous gimmick, Counting can seem a bit vaporous; it may try the patience of those who expect that even reveries will have a little bit of shape. In lieu of the overarching pretensions of a Godfrey Reggio, whose Philip Glass-scored travelogues seek to inform us about the way we live now, Cohen presents himself humbly as nothing more than a man with a (digital) movie camera. His film is vivid and yet elusive. He shoots first so that we might ask questions later.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.