Fear Street, a narrow street that wound past the town cemetery and through the thick woods on the south edge of town, had a special meaning for everyone in Shadyside. The street was cursed, people said. The blackened shell of a burned-out mansion—Simon Fear’s old mansion—stood high on the first block of Fear Street, overlooking the cemetery, casting eerie shadows that stretched to the dark, tangled woods. Terrifying howls, half-human, half-animal, hideous cries of pain, were said to float out from the mansion late at night. People in Shadyside grew up hearing the stories about Fear Street—about people who wandered into the woods there and disappeared forever; about strange creatures that supposedly roamed the Fear Street woods; about mysterious fires that couldn’t be put out, and bizarre accidents that couldn’t be explained; about vengeful spirits that haunted the old houses and prowled through the trees; about unsolved murders and unexplained mysteries.

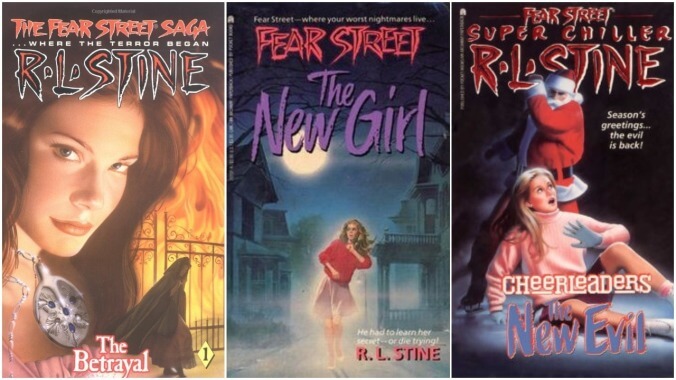

How’s that for a thesis statement? Stine clearly had grand ambitions, which he mostly realized between 1989 and 1999; then Fear Street went dormant until a 2014 revival. The New Girl (1989), though, is thuddingly simple—boy obsesses over the girl of the title, but, alas, she might be a ghost. “[H]e knew she was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen,” Stine writes. “Hauntingly beautiful. The phrase popped into his head.” Like many of Stine’s standalone books, the entire story is built on deception, both from the villain and Stine himself, who does everything in his power to lead you down the wrong path. In the end, she’s not a ghost, but rather a lunatic who murdered her own sister and has been assuming her identity.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because Stine went to this seems-paranormal-but-isn’t well a lot. When we spoke with Lindsay Katai and Kelly Nugent of the Teen Creeps podcast, the pair admitted that, in retrospect, most of Stine’s plots are a “blur.” A podcast about “the YA pulp fiction of their awkward, neon youth,” Teen Creeps dissects the work of Stine, Christopher Pike, Lois Duncan, V.C. Andrews, and even Francine Pascal and her horror-filled Sweet Valley High detours. The podcast hosts have read roughly 30 of Stine’s books over the last few years, ranging from his one-and-done slashers to his multi-volume series, which range from the teen-demon horror of Cheerleaders to the baroque melodrama of the Fear Street Saga. While many of the actual stories might fade from memory, the deaths themselves don’t.

Nugent and Katai recall Silent Night, wherein a girl’s mouth is gashed open by a needle that’s been stuck in her lipstick. There’s also Lights Out, a camping slasher where a girl’s face is rubbed to mush after it’s pressed into a spinning pottery wheel. Nugent praises Stine’s talent for creating an “iconic death”; for every character that’s shot or stabbed, there’s usually one that dies in an infinitely more creative fashion. Decades later, it’s tough to forget Cheerleaders’ Bobbi getting boiled alive in the school showers, or Saga’s Hamilton getting crunched and dredged by an ever-rotating steamboat wheel.

But Stine wasn’t just violent. He was also weird as all hell. Take the 99 Fear Street series, which ended its first volume by jettisoning a character’s brother and dog to an alternate realm before drowning her in what Katai calls “supernatural, evil hot tar.” In Sunburn, a book that highlighted horrors in an otherwise idyllic beach house, a woman “gets chased into the ocean by a vicious dog, a shark comes, and she has to fight both the shark and the dog,” recalls Katai. “Eventually, the shark eats the dog.” Nugent remembers a Saga moment where a guy’s head explodes, only for another, much more evil head to pop out from his shattered skull. It was a quite a journey, then, from the tame melodrama of The New Girl to Stine’s loonier later entries.

Fear Street books appealed to kids for plenty of reasons—they were short, straightforward, and packed with teenage themes—but the offbeat zaniness of their violence served to lessen the emotional impact, allowing the books to operate more like B-movies than serious drama. It’s interesting to measure them against a series like Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games, which couches its slaughter in a story of dystopian revolution. The same can be said for a ton of today’s most popular YA fiction, including the Divergent and Maze Runner books.

“It’s such a crazy difference between the teen horror [of] the ’80s and ’90s and YA today,” Katai says. “YA today is so steeped in taking down a corrupt dystopian world. This was purely about taking the tropes of being a typical American teenager and turning them into a horror show. Going to the beach is dangerous, going to prom is dangerous, having a boyfriend is dangerous.”

Although our fears of totalitarian dystopias aren’t likely to fade anytime soon, the pulp horrors of Fear Street might be gearing up for a comeback. Not only has Stine returned to the series in recent years, but, in February, 20th Century Fox announced that it’s throwing its weight behind a trilogy of Fear Street films from Honeymoon’s Leigh Janiak. Filming reportedly began in March, with Gillian Jacobs and Stranger Things’ Sadie Sink starring alongside Kiana Madeira and Olivia Welch. At the time, it was said the film would follow two gay teenagers “trying to navigate their rocky relationship when they’re targeted by the crazy horrors of their small town, Shadyside.” The films will reportedly leap between the mid-1990s and the 1600s, and could be released in “close proximity” to each other, an approach that would mirror the release schedule of the books in their heyday.

That’s all certainly in the spirit of the franchise, but can Stine’s gruesomeness be manifested onscreen in a way that won’t alienate the audience it’s trying to court? Can his R-rated content be adapted to a PG-13 aesthetic? Furthermore, will his kooky humor and soap-opera theatrics, both Fear Street staples, still resonate for an audience raised on a steady diet of socially and culturally conscious YA? At the height of its popularity, Fear Street mirrored the popular horror movies of its time, which were built more on set pieces than story. In this era of director Jordan Peele, art-heavy horrors like Midsommar, and the mythology-laden Conjuring franchise, that’s no longer the case.

Still, there’s something to be said about the simple pleasures of the slasher, that most resilient of genres. Horror studio Blumhouse, after all, is doing its part in reviving its patriarch, Michael Myers, with a new trilogy of Halloween films, and Fear Street could benefit from a renewed interest in the killer’s particular brand of “iconic death.” Horror doesn’t always have to be horrific. Sometimes it’s just supposed to be fun.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.