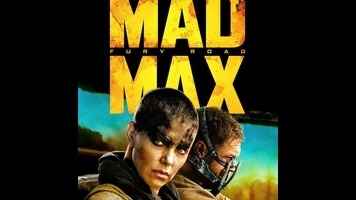

With Fury Road, Mad Max roars triumphantly back into theaters

Diesel and dust, blood and fire: Mad Max: Fury Road runs on all of it, flooding its fuel tanks to stay in perpetual motion. Forgive the wordplay, but this is the kind of movie that turns even timid drivers into fanatical car nuts. For two breathless hours, the vehicular mayhem never lets up. Spiked dune buggies, like porcupines on wheels, burn rubber and scratch metal. All-terrain gas guzzlers flip through the air, their rusty steel frames crunching and combusting upon impact. On the hoods of these speeding war machines, ravaged travelers battle with fists, pistols, and even chainsaws. To single out a favorite image from this flurry of nonstop shock and awe would require committing all of it to memory. But here’s one contender: a masked musician, perched high on a mobile stage, serenading his fellow marauders with triumphant power chords. He supplies the appropriate soundtrack for this rock-’n’-roll apocalypse. Also, his guitar is a flamethrower.

With Fury Road, director George Miller returns to the lawless, oil-deprived future of his seminal series for the first time in three decades. It was worth the wait. Each Mad Max film has been bigger and more expensive than the last, the scale expanding exponentially from the frugal road rage of the 1979 original to the increasingly elaborate dystopias of The Road Warrior and Beyond Thunderdome. Here, the budget races across the nine-digit line and it shows. Some directors don’t know what to do with that much money, relinquishing control and losing personality in the face of hefty studio investment. Not George Miller. Rather than cede demolition duties to a digital team, the filmmaker pours most of his pennies into the lost arts of daredevil stunt work and real pyrotechnics. The result feels like the closest Miller has ever come to getting the noisy, spectacular action movie in his head—the Mad Max he could only dream about in his fledgling years—up there on-screen.