In this case, that includes shooting in a variety of low-resolution and HD formats, including 3-D GoPros and a stereoscopic rig co-designed with his cinematographer, Fabrice Aragno—a wooden box with two DSLRs mounted inside, with both cameras capable of swiveling independently of one another, creating a hallucinatory effect in which one of the viewer’s eyes appears to migrate to the side of the head. Almost every medium hits a turning point when it moves away from representing reality to creating a reality of its own; this is the turning point for 3-D.

What Goodbye To Language presents—with its nonstop chatter, its endless musical and literary quotations, and its silly puns and poop jokes—is a dense, expressive, aggressive new medium rich with possibilities for juxtaposing images and creating meaning. In many ways, it’s a typical, tightly stuffed late-period Godard movie. There are circular domestic scenes, which were presumably shot in Godard’s own home in Rolle, Switzerland; harbor scenes, with ships arriving and departing in the background, which appear to have been filmed at the port of Ouchy, in nearby Lausanne; shots of a dog—Roxy Miéville, the filmmaker’s dog—sniffing around the countryside; shots of cars trudging along snow-packed Swiss highways, their windshield wipers struggling against the sleet; a sequence of Mary Shelley (Jessica Erickson) being rowed out across Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816; distorted clips from movies, including early special-effects extravaganzas like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde; and tables piled with books, ranging from A.E. Van Vogt’s The World Of Null-A to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Demons.

In other words, nothing in the movie seems to originate from a point that isn’t within driving distance of the filmmaker’s house, and much of it seems to have been pulled from the shelves of his own library. Godard—who created cinema’s most indelible and imitated image of the cosmos by stirring a cup of coffee—is a poet of commonplace objects. This is as true of his iconic urban movies as it is of his later domestic work: the bare apartments of his 1960s films, transformed into galleries by the addition of an artlessly tacked-up magazine clipping or print; the nighttime Paris of Alphaville, reworking into a city of the future that is, in turn, a metaphor for the present; the posters, advertisements, and logos that seem to bounce off his New Wave characters, producing meaningful rhymes.

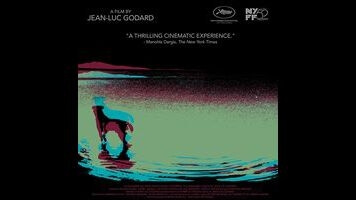

With a few early exceptions—most notably Vivre Sa Vie, the closest the filmmaker ever came to structuring a movie around drama and character—Godard’s narratives and characterizations have mostly functioned as frameworks for observations, reflections, allusions, and quasi-paradoxical arguments. There are a couple of very simple narratives in Goodbye To Language: the breakdown of the relationship between a married woman (Héloïse Godet) and her lover (Kamel Abdeli), and the story of a dog (the aforementioned Roxy Miéville, the real star of the film, afforded many loving close-ups) contemplating the world with a newfound self-awareness. These are interspersed with scenes of mock intrigue featuring figures in raincoats and fedoras and intimations of some kind of revolt, genre and politics breaking down in the world outside the house where the couple meets. Considering how tantalizing Godard’s obscure and knotty structures can get, the movie’s simplicity—and occasionally cranky asides about modern technology—might come as a letdown to diehards, though it makes for an easier entry point for late-Godard first timers.

Goodbye To Language’s two focal points—the end of communication, represented by the human world, and the birth of discourse, represented by that adorable, adored dog—are like different planes in one of its brain-scrambling 3-D images. For Godard, the new medium represents a boundless potential for wrapping and layering; it can show the death of something at the same time as it shows its rebirth.