In the damnably nice middlebrow race dramedy Green Book, two unlikely travel companions—one black and urbane, the other white and uncouth—pile into a gleaming turquoise Cadillac and venture off into the Deep South, bickering and bonding and gradually closing the gaping cultural chasm between them. It’s a time warp of a crowdpleaser, but not to the time you might think. Because though the film is set in the 1960s, what it really recalls, with no small amount of nostalgia, are the earnest and self-congratulatory social-issue pictures of the late ’80s. These were movies that looked backwards, to the troubles of a less enlightened past, in order to make their audiences feel better about the present. No wonder Green Book, which is like an inverted Driving Miss Daisy by way of Rain Man’s mismatched-buddy road trip, is already earning ovations: Intentionally or not, it flatters the delusion that racism, in its ugliest form, is more of a past-tense problem.

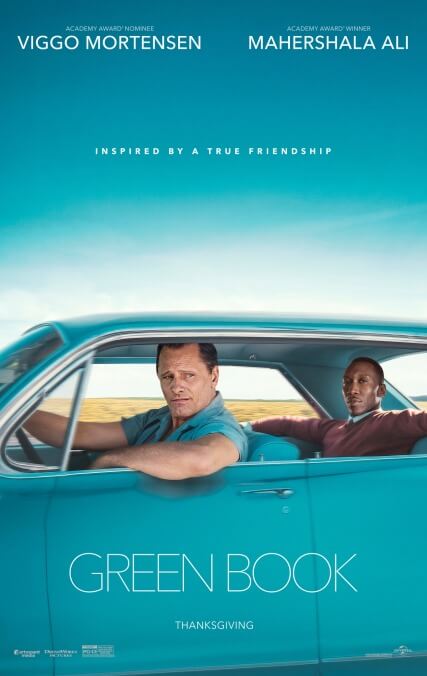

This is a true story, of course, as all truly inspirational ones are. In the 1960s, Don Shirley, a classically trained Jamaican jazz pianist, embarked on a concert tour, playing swanky Southern venues for exclusively white audiences. It was the Jim Crow era, though, so he needed a driver who could handle the wheel and get out of a tight spot if they got themselves into one. He found such a man in Tony “The Lip” Vallelonga, then a bouncer at the Copacabana, later a bit player in mafia-themed touchstones like The Godfather, Goodfellas, and The Sopranos. Green Book, which is named for a reference guide that once pointed black motorists toward hotels where they could stay, dramatizes the pair’s time on the road—and blossoming friendship—as a classic odd-couple pairing: Dr. Shirley (Moonlight’s Mahershala Ali) is the uptight, standoffish intellectual, rolling his eyes at his new chauffeur, who don’t read or talk so good, but when it comes to trouble? Fuggedaboutit!

As it turns out, Tony (Viggo Mortensen) isn’t just a buffoonish chatterbox. He’s also a racist lunk, the kind of guy who’d throw away a glass after a black man drinks from it. But his prejudice ends up looking casual compared to the kind Dr. Shirley—or “Doc,” as Tony calls him—encounters at almost every stop of the tour. And as the two head deeper south, their antagonism shading into affection, Tony’s attitudes begin to shift. From a distance, this all might seem like new territory for writer-director Peter Farrelly, one half of the sibling filmmaking duo behind There’s Something About Mary and other variably funny yuk- (and yuck-) fests. Yet there’s always been a strong sentimental streak to even the Farrellys’ grossest comedies, to say nothing of the number of road movies the brothers have made together. (Bobby, alas, has sat this one out.)

Still, Green Book works best at its most overtly comic, playing up the conflict between its mismatched travelers and leaning on a pair of committed performances. Mortensen, who put on about 50 pounds for the role, somehow manages to make Tony a barn-door-broad caricature of Italian NYC braggadocio (at one point, he folds a whole pizza in half and eats it like a sandwich) and a real character with flickers of an inner life. Between this and Captain Fantastic, is Mortensen now our go-to guy for finding the nuance in live-action cartoons? Here, the way he slowly deepens Tony, past the goombah routine of the early scenes, plays like an expression of the movie’s themes: a stereotypical idea of a person becoming an actual one the more time we spend with him. Ali, by contrast, does his best to ground the movie in emotional realism—in the Doc’s rage, loneliness, and dignity. He’s at once straight man and moral counterpoint to the absurdity of segregation-era America. (The whole dangerous tour, we come to understand, is a matter of principle: Dr. Shirley is exercising a privilege so many black artists of the time couldn’t.)

Much of Green Book is harmlessly hokey. It goes for easy uplift and low-hanging fruit, as in a subplot about Dr. Shirley doctoring Tony’s love letters to his wife, Dolores (Linda Cardellini), playing Cyrano de Bergerac for his emotionally limited companion. But there’s something a little tone-deaf, too, about how the film paints their dynamic. While we’re not necessarily supposed to approve of the way Tony scolds The Doc about not knowing Little Richard and forces him to try fried chicken, there’s no denying that, by the end, he’s helped this wealthy black artist—caught between two worlds, alienated by his class and his race—feel more in touch with black culture. However much the film acknowledges Tony’s failings, it also keeps putting Dr. Shirley in his debt: for rescuing him from violent racists, for sticking by him to the end, for accepting him for who he really is (including during a scene which seriously stretches plausibility, given the decade, in favor of heartwarming surprise). At times, Green Book plays uncomfortably like a white-savior movie disguised as a slob-versus-snob comedy.

Perhaps that’s to be expected. Farrelly co-wrote the script, after all, with Tony The Lip’s actual son, Nick Vallelonga, which helps explain why Green Book often regards him as one might regard a bigoted relative on Facebook: Sure, he’s a little backwards, but he ultimately means well, just like the feel-good, lightly amusing message movie he’s headlining. Tony’s prejudice, rolled up like a pizza pie into his whole everyman-goofball shtick and perhaps too easily overcome, is contrasted with the truly ugly intolerance of the small-town South. That makes the film a kind of comforting liberal fantasy, a #NotAllRacists trifle that suggests that our deep, festering divisions can be sutured through some quality time on the open road, resolving differences over a bucket of KFC. That’s a nice, hopeful thought that doesn’t quite gel with what the last few years have made clear about our national values. When it comes to race in America, and the movies about it, progress can be very slow.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)