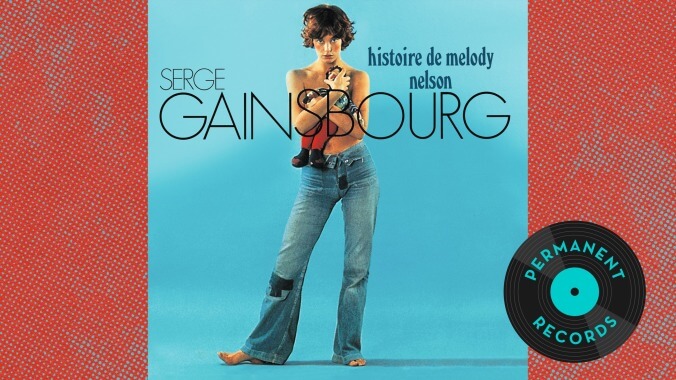

With Histoire De Melody Nelson, Serge Gainsbourg composed a French sex god’s teenage symphony

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuire

On April 5, 1986, French singer Serge Gainsbourg told Whitney Houston on live TV that he wanted to fuck her. Looking like a severely bee-stung Thom Yorke with eyelids heavy enough to dam a river, Gainsbourg slurred the come-on in unmistakable English in front of a live studio audience on Michel Drucker’s Champs-Élysées talk show. Houston, in the full flush of pop stardom from her debut album topping the Billboard 200 chart, sat in her chair, open-mouthed and aghast, while Drucker (France’s equivalent of Jay Leno and Jimmy Fallon if you mixed them together and stripped them of their few redeeming qualities) desperately tried to do damage control: “He says you are great.”

It’s a testament to how on one Serge Gainsbourg was in 1986 that telling Whitney Houston he wanted to fuck her on live TV wasn’t even the most outrageous thing he did that year. He also played an alcoholic and suicidal widower opposite his real-life teenaged daughter Charlotte in Charlotte For Ever, a controversial film that dredged up the off-putting themes of the Gainsbourgs’ hit 1985 single, “Lemon Incest.” Serge, an anxious introvert who grappled with stage fright over the course of his life, delighted in épater la bourgeoisie—his career was marked by one scandal after another, earning infamy and enmity at home and abroad.

When Gainsbourg died in 1991, the singer who was once dubbed “a walking pollution” by French journalists was hailed as a national hero. President Francois Mitterrand praised the singer by saying “he has raised the song to the level of art.” An artist who gained international notoriety by recording an orgasmic duet with his girlfriend in 1969, Gainsbourg was now receiving hosannas from heads of state. It’s hard to imagine a similar thing happening Stateside—it’d be as unimaginable as Barack Obama adding “Fuck The Pain Away” to one of his presidential playlists or Nancy Pelosi hailing the poetic genius of Kool Keith’s porno raps.

While Gainsbourg gained his cultural disrepute for his scandalous behavior and for dating the way-out-of-his-league likes of Brigitte Bardot and Jane Birkin, he was also a pivotal figure in the history of French pop music, as essential to the development of the form as The Beatles were to the U.K. and Elvis in the U.S. The skeleton key to understanding how Gainsbourg “elevated song to the level of art” in France is the 1971 concept album Histoire De Melody Nelson. It’s a record that Beck once called “one of the greatest marriages of rock band and orchestra that I’ve ever heard”—an endorsement that’d be evident throughout his sad-bastard classic Sea Change even without the “Cargo Culte” sample on “Paper Tiger.”

By the time Gainsbourg started working on Melody Nelson, his career had already gone through several major stylistic shifts. Initially getting his start in the same lush, piano-driven world of chanson where other singers like Edith Piaf and Jacques Brel had made their name, Gainsbourg became an in-demand pop songwriter during the ye-ye movement—France’s version of America’s girl group craze—penning some of the biggest hits of the era for singers like France Gall and Francoise Hardy. He experimented with African and Latin rhythms on his 1964 album Gainsbourg Percussions, and in 1968 found his “classic” style on Bonnie & Clyde and Initials B.B.: the sleazy maestro waxing pornographic in-between puffs of cigarette smoke, a Gallic Lee Hazlewood to his Nancy Sinatra of the moment. When his duet with partner Jane Birkin, “Je T’aime… Moi Non Plus,” blew up in 1969 and became a worldwide smash, Gainsbourg essentially got carte blanche to do whatever he wanted on his next album. And what he wanted to do was Nabokov.

Gainsbourg had become fascinated with the Russian author’s Lolita and wanted to adapt it, but got beaten to the punch by Stanley Kubrick. “I even asked Nabokov if I could put his words to music but he refused, because they were in the process of making the film of his book,” Gainsbourg said. The idea of writing a song cycle about a creepy, sad man’s objectification of a girl would stay with him, though, and led him to create Melody Nelson.

The lush opening track, “Melody,” immediately drops the listener into the ominous, sensual vibe of the record. Gainsbourg narrates from behind the wheel of a Rolls-Royce, cruising the streets while the bass plucks and resonates with noirish intensity. The orchestra swells and recedes into silence through sudden bursts of volume, flashing out like a needle being threaded in and out of dark cloth. There is so much space and emptiness in the production—the song flows like a series of held and exhaled breaths. As it builds to its climax, with the narrator accidentally (?) hitting the red-headed teenager Melody with his car, the strings erupt like a Bernard Herrmann sting in a Hitchcock film.

Darran Anderson, in his excellent 33 1/3 book about the album, proposes that one of the driving forces behind the album was Gainsbourg’s jealousy of Birkin’s ex, film composer John Barry. It’s not hard to believe when you consider how cinematic Melody Nelson sounds. Each of the songs on the record feels like a discrete scene, spelling out the doomed relationship between Gainsbourg’s seedy French lothario and the English teen Melody. “Ballade De Melody Nelson,” with its sprightly guitars and Serge’s contented “ahhhh Melody” vocals is the sound of infatuation, of a crush blooming into full flower. The grey waltz of “Valse De Melody” is the moment where things turn serious, where his narrator commits to seducing the girl. The triptych of “Ah! Melody,” “L’hôtel Particulier,” and “En Melody” (“In Melody,” the song title’s translation, in case you couldn’t figure out what it’s about from the jazzy porn music and Birkin’s giggling voice) follows Gainsbourg from making his move to sealing the deal. And “Cargo Culte,” a musical reprise of the opening track, ends the story the only way it could possibly end: tragically.

Gainsbourg worked with a pool of collaborators on Melody Nelson that included bassist Herbie Flowers (whose fat bass notes would be all over the radio a year later on Lou Reed’s “Walk On The Wild Side”), Jane Birkin (both the voice and face of Melody—it’s Birkin, four months pregnant at the time, posing topless with a toy monkey as Melody on the album cover), and orchestral arranger Jean-Claude Vannier. “You are Cole, I am Porter,” Gainsbourg once said to Vannier, and you can hear that symbiosis all over the record.

A film scorer like Barry, Vannier’s unique style of arranging is what gives Melody Nelson such a distinct vibe—the only other record that exists on a similar wavelength to it, in terms of how it treats the orchestra like a breeze that blows in and out of the track without warning, is Isaac Hayes’ 1969 release Hot Buttered Soul. Both albums feature singers who talk over long, sinuous tracks while other voices (like the massed choir “aaah”ing to the heavens in “Cargo Culte”) do the heavy emotional lifting. But whereas Hayes’ voice is rich in subtle feeling on Hot Buttered Soul, Gainsbourg keeps the same energy in his voice: the weary croon of a man who knows he’s damned and takes a faint, grim satisfaction from it.

Gainsbourg would record other ambitious albums in his career: 1975’s bee-bop-a-loo-bop classic rock album about the Nazi occupation, Rock Around The Bunker; 1976’s psychosexual fantasy L’Homme À Tête De Chou; and a pair of reggae albums he made in 1979 and 1981 that would garner him death threats from conservatives in France who did not take kindly to him skanking all over “La Marseillaise.” None of them hold together as well as Melody Nelson, a record that encapsulates what makes Gainsbourg great: His commitment to the bit, his ability to deftly blend genres together, and his willingness to explore taboo subject matter without worrying about how it would make him look.

And none of Gainsbourg’s records would get an ending as perfect as “Cargo Culte.” Returning to the noir crawl of “Melody,” “Cargo Culte” finds Gainsbourg watching Melody fly home and praying that an accident happens, that some malfunction will turn the plane around and bring her back to him. He compares himself to the cargo cults of New Guinea, petitioning the spirits to down a plane and bring an offering to him. But the plane crashes, killing Melody instead, leaving Gainsbourg’s narrator stranded in his aging body, as alone in the world as a marooned man on an island.

Melody Nelson isn’t much of a character. She’s an object on the album, a vessel for the narrator’s twisted lusts and anxieties about aging. Much in the way that Whitney Houston was an object for Gainsbourg in 1986: someone he could use to shock an audience and get his revenge on a talk show host for mistranslating him. But he does say something to her later that’s kinder: At least he tells Whitney her voice is sublime.

You can also hear the sublime in “Cargo Culte”: As the song heads toward its last minute, Vannier brings in a massed chorus whose voices build in intensity, a heavenly choir that drowns out Serge and bears Melody’s soul up into a heaven he’ll never be allowed entry into. Brian Wilson once said he was writing teenage symphonies to God. On Melody Nelson, Gainsbourg wrote a symphony to God about a teenager. He just had the good sense and humility to cast himself as the Devil in it.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.