Twenty-two years is an enormous chunk of life to sacrifice to a false prophet and his empty promises of spiritual salvation. But when budding filmmaker Will Allen emerged from the cult that had used and abused his devotion for more than two decades, he at least had something to show for the time lost: reels upon reels of footage, the cinematic record he had amassed as the group’s official documentarian and unofficial propaganda minister. Holy Hell is the fruit of that labor. Through a combination of his vast library of home movies and a series of talking-head interviews conducted with his fellow duped, Allen invites audiences to relive all 22 years spent under the spell of a charlatan; he’s reverse-engineered an undercover exposé of life within a cult. But is seeing this mass deception in action the same thing as understanding it? Can images and testimonials alone provide the whole story?

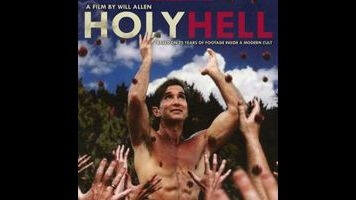

It would certainly take more than what we glimpse in Holy Hell to grasp the magnetic appeal of Michel, the slimy self-made guru of Los Angeles-area spiritual group The Buddhafield. Described by one of his former followers as “an out-of-work actor who found the role of a lifetime”—he appears as one of the satanic groupies in Rosemary’s Baby, ironically enough—Michel came to America in search of movie stardom, then pivoted to porn before landing on New Age leadership as an alternative route to the perks and sycophantic adoration he craved. To outsiders watching these celluloid transmissions from the group’s earliest days, Michel looks from the very start like the creep he is—a narcissistic weirdo in sunglasses and a speedo doing a bad swami imitation. Holy Hell tries to illuminate how that cheesiness, that aura of L.A. wannabe celebrity, was all part of his huckster shtick, the way he seemed to update the principles of the flower-power era for a modern, looks-and-status-obsessed California. He was selling old wisdom in a new package.

The film basically begins in 1985, when Allen—a film-school graduate ostracized by his mother after coming out—joined the more than 100 other men and women who first became consumed by the rituals of “The Teacher.” Condensing, a little too neatly, a full two decades into an hour and 40 minutes, Allen takes us from the movement’s idyllic roots (clean and communal living; constant support and validation) to its painful decline, as Michel’s utopian philosophy slowly reveals itself to be a backdoor to self-glorification. If nothing else, Holy Hell conveys the practicalities of how the “common” cult functions, showing each step of The Teacher’s long con: the $50 therapy sessions (or “Cleansings”) that get followers hooked on expensive false catharsis; the strategic withholding of spiritual enlightenment (or “Knowing”) to keep everyone obedient; and the granting of new names and cutting off of ties with family, to assure that members are in too deep to ever leave. It’s like a ground-level Going Clear, exposing the inner workings of a much-smaller-scale spiritual scam.

Holy Hell has an undeniable car-crash fascination, especially once Allen reveals just how deeply this particular phony guru abused the trust of his faithfuls. Withholding information can be a cheap trick in documentary filmmaking, but the belated, chronology-bending revelation of Michel’s darkest offenses works less as a rug pull than a nod to the repression and denial that kept The Buddhafield afloat. What the film never quite communicates, what it can’t communicate, is the scary pull The Teacher had on his disciples. “How did this happen to you?” someone absently asks himself toward the end of the film, and you watch Holy Hell in search of an answer. But none of the archival evidence Allen has assembled manages to convey the leader’s charisma or draw—to let the audience see him through his followers’ blinkered eyes. The filmmaker commits that cardinal cinematic sin of telling instead of showing, montaging through sound bites of his subjects briefly explaining what led them down this path and what they saw in Michel. The film leaves you wanting to know much more than its offhand footage and scant 100 minutes can provide.

Still, maybe that lack of connection—that inability to become immersed in what these people were feeling, to comprehend the allure of the oddball fraud whose feet they kissed—is perfectly apropos. Late in the film, one of the disciples confesses that acting against Michel in one of Allen’s glorifying short films helped him finally realize that the whole movement was a kind of performance, a fiction. Perhaps Holy Hell serves the same function for Allen: By sifting through all this old imagery of his life, by seeing his memories dispassionately captured through the eyes of the camera lens, he can finally see Michel for who he really was—and hopefully in the process, cleanse himself of the man’s influence once and for all. The film feels, foremost, like an exorcism, and it’s poignant to see these survivors reclaim their identities on camera, to come through the other side stronger. Maybe Allen got more than a treasure trove of first-person footage from his difficult experience. Maybe, as Holy Hell provocatively suggests, the cult saved his life. Or escaping it did, anyway.