Louis C.K. is in this rare place culturally where he has enough clout and money to fulfill any and all of his artistic desires. There’s no longer any timetable or sense of urgency for his projects. He can release another stand-up special or film another season of Louie whenever he pleases, or he can just act in other people’s movies and produce shows like Baskets from now until forever. But as anyone who has followed his career already knows, Louis always keeps busy by throwing himself into whatever creative project tickles his fancy and often does so secretly. Case in point: Last Saturday, he dropped the first episode of a web series called Horace and Pete on his website for $5. There was no announcement or previous mention, just an email notice to subscribers of his mailing list on the day of the release. Before yesterday, we had no idea if there would even be another episode in the pipeline. All we got was an hour-long teleplay about an Irish bar and the sad denizens who keep it alive.

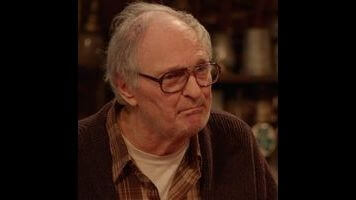

Horace (Louis C.K.) and Pete (Steve Buscemi) are the co-owners of a 100-year-old Irish bar of the same name. They are the seventh generation of Horace and Pete’s who have owned the bar. They have regular customers, like the sardonic Leon (Steven Wright), the nihilistic Kurt (Kurt Metzger), and the conservative assistant D.A. Nick (Nick DiPaolo). Their resident bartender is Uncle Pete (Alan Alda, with his very best performance in about a decade) who rules the atmosphere in the place with an iron fist of negativity and black humor. There’s also Marsha (Jessica Lange), Horace VII’s final lover, who drinks at the place because, presumably like the others, she’s always drank there, and she always will. Horace and Pete is founded on tradition—it was started by a Horace and Pete and will continue to be run by a Horace and Pete, no matter what—and everyone who resides there, subconsciously or not, wants to keep the tradition alive. But Horace’s sister Sylvia (Edie Falco) wants to sue Horace and Pete for her rightful share of the bar, and ultimately sell it because she sees what no one else wants to see: The bar is a miserable prison stuck out of time and perpetuating it for no other reason than because of “tradition” will ruin them all.

On some level, Horace and Pete is an experiment, and it can be read that way. Louis is riffing on a lot of different influences, with the obvious one being Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, but there’s also Cheers, Playhouse 90, Norman Lear’s ’70s shows, Mike Leigh’s TV productions, and the work of playwright Annie Baker (who is specially thanked at the end of the first episode’s credits.). There’s a flash-in-the-pan quality to the first episode as it appears to have been filmed and edited very quickly, hence the topicality of the political discussions. Everything’s a little rough around the edges, especially the filmmaking, which is clearly for coverage over style, but including the writing as well, which can be a bit heavy-handed at times. It’s easy to look at this as a pet project, shrug your shoulders, and move on,

But frankly in spite of its roughness, Horace and Pete’s first episode is a devastating exploration of collective illusions and divisions, about how being stuck in your own myopic worldview separates you from your neighbor and makes you blind to changing realities. Uncle Pete clings so desperately to How Things Were that he casually forgets that things weren’t ever that great. Young liberals and old conservatives bicker over politics without once realizing that they’re starting from places of bad faith (“Who says they want consensus? They’re not trying to reach an agreement. It’s fuckin’ sports,” sneers Kurt). Horace can’t connect with his estranged daughter because he can only relate her happiness to his own sense of self-worth. And Pete, one of the few sensible, kind people in the bunch, is slowly losing his grip on reality.

The establishment itself is toxic, founded on abuse and neglect. Regulars come in to get loaded on watered down booze (“You know what would happen if we serve un-watered whiskey to these rummies? Half of them would be dead years ago,” Uncle Pete says in justification), happy to sit and bitch about the same problems day in and day out. Uncle Pete kicks out all the young hipsters who come in to the bar because they dare to ask for mixed drinks and bottled beer. But everyone casually ignores the truth that the world outside has changed. It’s only Sylvia who reminds everyone of how many wives were beaten in Horace and Pete’s, and how it was a place of escape for patriarchs who didn’t want to be with their families. “100 years of misery is enough, Pete!” she exclaims. “Misery is something you get past, not something you pass on to your children.” But it’s a futile endeavor. Horace and Pete’s is a self-sustaining business, kept alive in spite of its poor management because of an empty tradition. If Cheers was a place where everybody knew your name, Horace and Pete is a place where no one gives a fuck about your name even if they already know it.

It’s a dark show made darker by casual revelations, such as Uncle Pete dropping the bomb that he’s Pete’s father but never told him because he “doesn’t like kids,” and the fact that nothing gets even remotely resolved. Sylvia yells at Uncle Pete that it’s time to let go of a tradition that has only caused people pain; Uncle Pete yells that the tradition is sacred because it’s lasted so long. Pete yells at all of them to face each other and see each person’s side. But no one listens. Everyone’s blind to the person next to them, as they all hold onto the poor lessons they’ve learned from those that came before. It’s why Horace callously breaks up with his girlfriend Rachel (Rebecca Hall) even if it’s to theoretically get his daughter to move in with him. It’s why Sylvia falls back into the same old patterns even though she escaped a long time ago. It’s why everyone conveniently ignores Pete’s pain until they can’t any longer. Nothing changes because no one wants it to, and even if they do, there’s no telling if they even can.

It’s difficult to say where Horace and Pete goes from here. It’s reasonable to assume that some plotlines will be carried over, such as Sylvia’s suit against the bar and Horace’s attempts to reconcile with his daughter, but it could also be just a stand-alone episode. It could be funnier or could be even darker. (Not that the first episode isn’t at all funny; almost every minute Alan Alda is on screen is hilarious.) But one thing that’s hard to deny is that it’s a show about the culture as it stands now. At a time when populist rancor is at a high and people are holding onto familiar fears because it’s better than embracing something new, what could be a better time for a show that externalizes that sentiment? Horace and Pete captures the moment when everyone has held on for far too long, but no one’s willing to face up to the reality.

Stray observations

- Louis is dropping a new episode tomorrow morning. A review will be up at some point during the day.

- If you’re wondering who wrote the fantastic theme song, it’s Paul Simon. Yes, the Paul Simon.

- People thanked at the end of the credits: Annie Baker, Joe Pesci, Lorne Michaels, Pamela Adlon, Mike Leigh, and Mary Szekely.

- I cannot stress enough how funny and brilliant Alan Alda is in this. This entire section could just be lines of his, but the humor gets lost without his delivery.

- Horace and Pete dancing in the beginning while they’re opening up the bar is one of the few purely sweet moments in the episode.

- Kurt thinks Trump’s slogan should be: “Let’s get this shit over with.” I don’t disagree.

- The discussion of the Super Bowl is interesting. Both Nick and Marsha don’t like Cam Newton, and Kurt surmises because they’re afraid of an exuberant black man.

- The conversation Horace has with his daughter, played by Aidy Bryant, is just devastating. You can see the years of hurt in her face.

- “How can you tell if he’s grinning under the helmet?”

- “Sometimes when there’s a conflict you can be kind of an asshole.”

- “Racist is what you do, not what you say.”

- “Wow, that’s really mean, Alice. I didn’t know you could be mean.”

- “So the tortoise cooked some eggs and the frog ate them?”

- “Fucking is how you make family.”

- “It’s not serious. It’s what it is.”

- Let’s close with Uncle Pete’s definition of a pissant: “A pissant is an insect with no value, but smells like piss. At least a cocksucker can do something, suck cock. But a pissant just sits there in the doorjamb smelling like piss.”