With Howard, Disney+ movingly honors the lyricist who gave the Little Mermaid her voice

After an early test screening of The Little Mermaid, Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg had one big note. The kids in the audience were bored by Ariel’s ballad about wanting to be human. “Part Of Your World” should be cut. Lyricist Howard Ashman put his foot down. He told Katzenberg they’d lose the song over his dead body. It wasn’t a metaphor he used lightly. Ashman had recently been diagnosed with HIV at a time when that was very much a death sentence. He spent his final few years pouring his heart and soul into the early films of Disney’s 1990s renaissance. He died at the age of 40.

As time marches on, there’s concern about how to make the scope of the AIDS crisis understandable to a generation too young to remember it. One answer comes in the form of Don Hahn’s new Disney+ documentary, Howard, which centers on a gay, HIV-positive man who played a major role in so many Millennial and Gen Z childhoods, even if they don’t know him by name. Ashman and his songwriting partner, Alan Menken, penned iconic songs for The Little Mermaid, Aladdin, and Beauty And The Beast, as well as the beloved cult musical Little Shop Of Horrors. In exploring Ashman’s phenomenal creative output, Howard inspires bittersweet reflections about just how much more he—and by extension, a whole generation of artists—could’ve accomplished had their lives not been cut short by AIDS.

Howard is a sort of sister project to Hahn’s 2009 documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty, which explored the broader creative and commercial background of the Disney renaissance—something Hahn experienced firsthand as the producer of Beauty And The Beast and The Lion King. Ashman featured in some of the most moving portions of that earlier doc (which is also streaming on Disney+), and Hahn has essentially expanded those segments into a feature about the artist’s life and legacy. The first half of Howard charts Ashman’s artistic youth and his rise through the ranks of the New York theater scene in the 1970s and early ’80s. The second zeroes in specifically on Ashman’s time at Disney in the late ’80s, which coincided with his HIV diagnosis.

Despite the clear affection Hahn feels for his subject—a lyricist who could dream up everything from the demented earnestness of “Somewhere That’s Green” to the verbal dexterity of a line like, “We’ll prepare and serve with flair a culinary cabaret”—there’s a book report-ish quality to the straightforward way Howard lays out Ashman’s biography. In place of on-camera interviews, Hahn plays audio commentary from Ashman’s friends, family, and colleagues over old photos and stock footage. It’s a stylistic choice that unfortunately proves distancing when it comes to making a connection to the regular players in Ashman’s life. Frequent Ken Burns-style zooms and pans call to mind a PowerPoint effect more than the master documentarian himself.

But if Hahn’s filmmaking struggles to replicate the whimsical creativity of his subject, Ashman’s genius shines through anyway. Howard makes the case that Ashman wasn’t just a lyricist but also a storyteller—one who got his start entertaining his kid sister, before going on to introduce Disney animation to the idea of using songs to advance plot and character. (A tribute at the end of Beauty And The Beast notes that Ashman “gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul.”) Howard’s most compelling moments come from Ashman himself in old interviews where he explains his creative process, like the way he approaches adaptation. Hahn has amassed an impressive amount of archival material from Ashman’s life, from old photos at the apartment he shared with his college boyfriend to work tapes of Ashman singing demos of his own biggest hits.

Hahn also roots Ashman’s story in the larger context of the AIDS crisis in New York City. Ashman saw friends die of the disease before it even had a name, and when he later started showing symptoms himself, he turned down his doctor’s suggestion of an HIV test because it could cause him to lose his insurance. (They did a T-cell count to confirm the diagnosis instead.) During the height of AIDS stigmatization, Ashman decided to keep his illness a secret for fear it could cost him his job at a family-focused company like Disney. Howard is full of heart-wrenching stories about how Ashman worked through his illness—secretly wearing a heart catheter during an eight-hour press junket for The Little Mermaid and later writing “Prince Ali” in his hospital bed with Menken on a portable keyboard.

Ashman died several months before Beauty And The Beast was released, and when he posthumously won an Oscar for Best Original Song, his partner Bill Lauch accepted the award on his behalf. In a landmark moment for LGBT visibility, Lauch explained that he and Ashman shared a home and a life together and that the win marked the first time the award was given to someone lost to AIDS. It’s a speech that still resonates, and interviews with Lauch add a welcome personal perspective to the story of a man whose life was so defined by his career.

Howard doesn’t shy away from Ashman’s demanding, perfectionistic streak—qualities that were potentially buoyed by anger about his illness. (Menken, who recorded a new score for this film, recounts a time Ashman smashed a tape recorder in frustration, causing Menken to leave the room in tears.) But the documentary mostly captures the soft-spoken, self-effacing sides of Ashman’s personality. While coaching Jodi Benson through the recording of “Part Of Your World,” Ashman pauses his lengthy list of notes to offhandedly reassure her, “By the way, your performance is fabulous.”

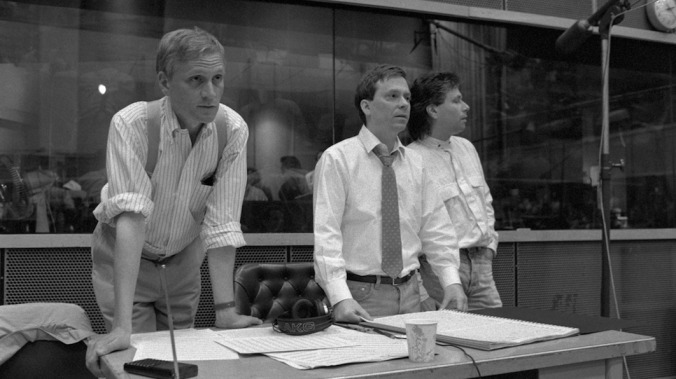

For both musical theater fans and Disney aficionados, Howard is a must-see. Hahn bookends the film with extensive footage from the recording session for Beauty And The Beast, in which Ashman watches with a critical eye as Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach perform “Be Our Guest.” But even for those outside of the Disney musical demographic, Howard is a moving portrait of an artist taken too soon during an era tragically marked by those kind of losses.