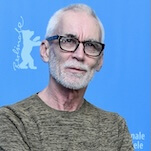

Clive Owen and Julianne Moore Screenshot: Lisey’s Story

Though it opens with an arguably unnecessary sequence between Jim Dooley and Professor Dashmiel—the same kind of psychopathic fandom babble we’ve heard before—the rest of Lisey’s Story’s fifth episode is a marvel. After the fake-out of the opening, the episode becomes primarily focused on one moment in the lives of its characters: Lisey being told the story of how Scott’s brother Paul was killed by his father. Reducing it to just an expansion of scenes between the couple that we’ve already been introduced to in past episodes would be unfair though, as it’s as interesting to watch as its own story in addition to as a part of a grander narrative.

“The Good Brother” bounces between three periods: Lisey’s post-torture shock, Lisey and Scott’s snowy vacation, and Scott’s childhood, but each complementing the other ideally. Even when we’re in a scene without Lisey, one can imagine that everything we’re witnessing is how Lisey pictures the story that Scott is telling her; a tale gruesome enough to make her want to forget about it as soon as it’s over, as she’s implied in the past. “Maybe that’s how your father felt,” she notes, trying to excuse her guilt for not wanting to understand Scott’s trauma and the magic that surrounds it. But, as we are all well aware, trauma can’t be ignored.

Just as the episode primarily focuses on Scott’s fucked-up childhood, I’ll do the same here. Where many Stephen King adaptations have tried to lazily capitalize on the horror of his narratives while ignoring the rich melodrama that comes with them (the recent It movies, particularly Chapter Two, being a major offender), the depiction of one month of Scott’s childhood balances both perfectly. Pablo Larraín and Darius Khondji offer some excellent horror framing in depicting Scott’s trauma. The way they shoot scenes emphasizes not only the distance that has grown between these characters who were once as thick as thieves, but how Scott is trapped between a rock and a hard place, torn between brother and father with no way to win.

The screeches that come out of Paul, and his fits and transformation from innocent child who has been cut by his father to “let the bad out” into shrieking beast hellbent on destroying Scott, are genuinely disturbing. Rather than escalate from one scene to the next, the creative team maintains a level of anxiety from the get-go. Paul scratching Scott and chasing him around like a zombie ready to consume what it sees is as harrowing as watching Paul trying to seduce Scott into unchaining him with his wicked words. And the make-up folks deserves special mention for the transformation of Paul from angel to devil, with each passing moment only increasing how grotesque and monstrous he looks.

It’s the kind of extended set piece that works right down to the score, which I’ve had my fair share of complaints about in prior episodes. The discordant soundscape that Clark creates for each instance of horror is exquisite, only enhanced when paired with the simple beauty of the recurring aural motif that comes with transitioning from “reality” to the Boo’ya Moon. And this all ties into the aforementioned balance of horror with melodrama. Part of the reason that the horror of “The Good Brother” works is because of its complementary pieces.

For the first time all season, we actually get the chance to see Michael Pitt engage in more than paranoid ravings as Scott’s father. His performance humanizes a character that could have been easily portrayed as exclusively horrible, and when the rain pours down on him, on his knees, it’s clear he’s hoping that it’ll wash away whatever sins he’s committed. It’s why when he says, “I love you too, kid. I’m sorry,” it rings as a sincere statement rather than an excuse for abuse.

One of the best parts of “The Good Brother” is the chance to see Clive Owen deliver this story. These recollections have weight, not simply because of their content, but because of the way Owen looks like he’s dissociating as he tells it. He’s consistently on the verge of tears as he speaks, his voice trying to be steady but clearly distressed, and the worry in Moore’s eyes only makes it all the more impacting.

Even when this extended memory is done, the episode doesn’t let up. For something that was so brutal, it is refreshing to be once again grounded in Lisey’s perspective and the way she moves through memories and spaces. There is beauty and horror in how Lisey navigates Boo’ya Moon when she first enters to find her husband. It lets us experience locations we’ve glimpsed before in gorgeous detail while also doubling down on the horror of this watery space that people inhabit.

Better still is the bit of the episode that climaxes by showing multiple scenes of Lisey’s memories cut together. Her realization of what she must do, her willingness to finally stop rejecting the past, and her preparation to leave “reality” to enter the Boo’ya Moon to rescue her sister, is just phenomenal. It’s all about going back to the first episode, too. Obviously the water visual motif has been around all along, but the pool itself is such a key image. This is a series that opens its present day timeline by showing us Lisey getting into the pool (at the moment void of the meaning that water would later have), sitting there and mourning. For Lisey to move beyond mourning and frustration, to become an active figure rather than a passive one in the lives of her husband and her sister, for her to embrace the fact that she has been a heroine all along by grabbing hold of the very same shovel she once used to save a life, is the perfect pivot for her to make halfway through the series.

Stray observations

- Am I the only idiot who heard “It’s the Landon curse, but it’s also a blessing” and immediately thought of Monk’s “It’s a gift…and a curse” line?

- To borrow a term from one of my favorite shows (Lost): I love this concept of “Too Late To Turn Back Now” being Lisey and Scott’s constant. In spite of all the events we’ve seen of them together, this dance and their wedding song is the thing that grounds their relationship is just kind of beautiful to me.

- That one latex-y body by the water in Boo’ya Moon has real “Ryan Murphy wishes he had this energy for American Horror Story.”

- Will say that the more I see the Long Boy design, the more I am sort of underwhelmed by it. It keeps making me wish they’d gone for an even more intriguing and messed-up depiction; something like Popolac from Clive Barker’s fantastic short story, “In The Hills, The Cities.” But maybe I’m just expecting too much and going a little more high concept than the show, or King, were.