It was a black-and-white image of diggers toiling in a muddy gold mine that first drew filmmaker Wim Wenders to the work of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado. There was something about these dirt-caked prospectors stretching as far as the eye could see that was unbearably moving. As Wenders describes it in the tender yet scattered tribute documentary he co-directed with Salgado’s son Juliano, here was an artist who clearly felt for the people he was capturing. And it’s true: Whether snapping single-person portraits or expansive group shots, each of Salgado’s subjects is a unique and distinctive being. Their individuality resonates despite the fact that the world weighs heavy on them, threatening anonymity.

Even when faced with death, Salgado manages to unearth an essence of life lived (or at least survived). A good portion of his portfolio was taken during the Kuwaiti oil fires and the Rwandan genocide, and many of the documentary’s most moving scenes occur when Salgado revisits these images of lifeless bodies and an environment under siege. Wenders will frequently fill the screen with one of the photographs, which is lit like a scrim so that a change in lighting makes the picture semi-transparent. This allows Salgado to lean forward and comment on his thought process behind the photo. His technical observations quickly become emotional. It was while working with Doctors Without Borders in Rwanda that he nearly lost his creative drive; the depths of inhumanity that he witnessed were almost too much to bear.

The film is, in large part, a story of an artist rediscovering his muse. Salgado first picked up a camera quite by chance, and only to photograph his wife as she stood in the sunlight on a Paris balcony. (The couple had moved to Europe to escape the military dictatorship then ruling Brazil.) But something about “painting with light”—as Wenders defines the Greek roots of “photograph” in the opening scene—called to Salgado, and he spent much of the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s documenting people in underprivileged circumstances.

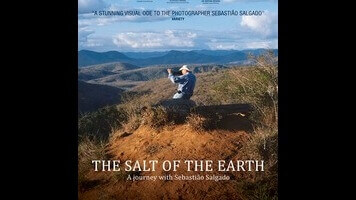

At first, The Salt Of The Earth feels more than a bit unbalanced as it chronicles Salgado’s continent-hopping journeys and the photography books that resulted. Wenders gives more prominence to his superficial musings about Salgado’s work than he does to a more intriguing thread—his younger co-director’s lingering discontent over the absent father who he is only now getting to know more intimately. Fortunately, the doc’s back half, which explores the creation of Salgado’s first book of landscape and nature photographs, Genesis, rights things by dealing with the artist’s own familial turmoil, which is inextricably intertwined with his aesthetic and emotional difficulties post-Rwanda. Wenders is on sturdier ground here, telling an affecting going-home-again story not so far removed in theme from one of his greatest fiction features (Paris, Texas), and revolving around a setting (a family farm fallen into disrepair) that works as redemptive and rejuvenating metaphor.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.