Woman In Gold gives a complicated true story the Weinstein treatment

For decades, art lovers in Vienna knew her only as the Lady In Gold, a nameless, raven-haired beauty immortalized through oil. But to Gustav Klimt, creator of this “Mona Lisa Of Austria,” she was Adele Bloch-Bauer, a Jewish socialite whose likeness the artist twice committed to canvas. Woman In Gold, about the real-life battle for a disputed national treasure, argues that hanging Portrait Of Adele Bloch-Bauer I under a generic new name—as The Belvedere did, years after Nazis stole it from Bloch-Bauer’s family—was emblematic of how Austria tried to paper over its involvement in Hitler’s reign of terror. That’s a credible thesis. It’s also pretty rich, coming from a film that performs its own historical makeover. An early contender for the most Weinstein movie of the year, Woman In Gold bends a complicated legal quagmire—heavy on questions of ownership and national responsibility—into a crowd-pleasing David and Goliath story. The title, too generic for Klimt’s masterpiece, suits the movie just fine.

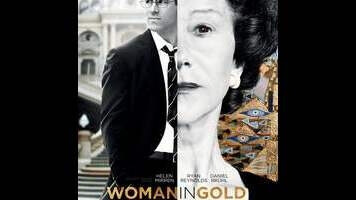

Swapping her native British accent for an impeccable Austrian one, Helen Mirren brings a zesty eccentricity to the role of Maria Altmann, grown niece of the lady in gold. In 1998, a half-century after she fled her homeland for the sanctuary of the States, the widowed Maria begins quietly investigating ways to reclaim the pilfered paintings, including the famous rendering of her late aunt. For legal counsel, she looks to Randy Schoenberg (Ryan Reynolds), whose grandfather, the revered Jewish composer Arnold Schoenberg, was a friend of the family. Randy doesn’t know much about art, nor does he have the full support of either his new boss (Charles Dance, doing another stern variation on Tywin Lannister) or his spouse (Katie Holmes, in a housewife role as thankless as the one she played for Tom Cruise). Nevertheless, the attorney’s interest is piqued, especially when he sees the price tag on that iconic artwork.

What follows is a kind of biographical buddy picture, entwining the fates of two easy-to-root-for characters: the driven survivor, forced to finally confront her traumatic past, and the crusading lawyer, putting everything on the line for a case he believes in. Despite vowing never again to set foot on Austrian soil, Maria begrudgingly accompanies Randy to Vienna, where the two enlist the assistance of a muckraking reporter (Daniel Brühl) in building a case against the Austrian government, whose officials are roundly depicted as a bunch of sour bureaucrats who talk of reparations but do everything in their power to prevent them. Alexi Kaye Campbell, the playwright who penned the script, does an admirable job of summarizing the complex legal maneuvering this odd couple engaged in. But he also manages to make real people look and sound like bantering archetypes. Randy, especially, could have walked out a John Grisham novel. (It doesn’t help that the green lawyer is played by Reynolds, poorly concealing his movie-star swagger behind a pair of just-passed-the-bar spectacles.)

In part, perhaps, to pad out the narrative, Woman In Gold also cuts away from its present-tense plotline for flashbacks to Maria’s youth, featuring Orphan Black’s Tatiana Maslany as the heroine’s younger self, attempting to secure safe passage out of occupied Austria. There’s a certain integrity to actually shooting these scenes in subtitled German, and the spectacle of shopkeepers forced to scrawl their ethnicity on the doors of their businesses will never lose its horrible historical resonance, even when staged with tasteful anonymity by My Week With Marilyn director Simon Curtis. (He makes one long for the relative verve of John Madden.)

By its second half, Woman In Gold has devolved into a series of time-passing montages and courtroom showdowns (including one that casts Jonathan Pryce, in an amusing cameo, as a Supreme Court justice). Mirren, who could play this part in her sleep, manages to keep the poignancy of her character’s plight simmering below the surface of most scenes. For Maria, the point of the whole fight isn’t money (though the Klimts would net her a pretty penny), but accountability: To wrestle the paintings from Austria would be to force the government to acknowledge complicity, and to really commit to efforts to make things right. At one point, the expatriate seems to admit that any victory would be a bittersweet one, as there’s no way to truly repair the damage the Nazis (and those that welcomed them with open arms) did to her life, her family, and the nation she once called home. On the whole, however, such ambivalence doesn’t fit Woman In Gold, a legal drama that aims for a much less prickly brand of cathartic comeuppance—the middlebrow equivalent of an “oh, snap!”