Wonder Woman was a beacon of hope during a dark political time

From her first big-screen appearance in the DCEU, Wonder Woman was breaking ground. Her solo movie still stands alone.

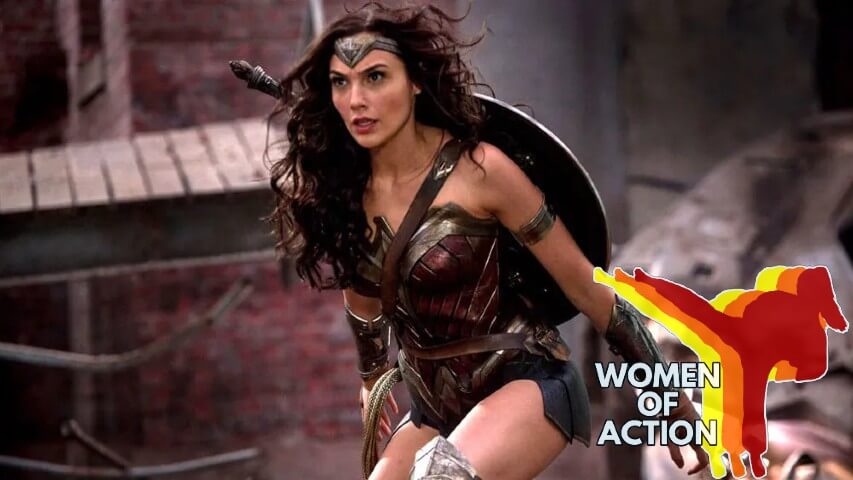

Photo: Warner Bros.

With Women Of Action, Caroline Siede digs into the history of women-driven action movies to explore what these stories say about gender and how depictions of female action heroes have evolved over time.

It’s funny how context can get lost with time. When I think back on the seismic cultural moment when Wonder Woman hit theaters, I remember stories of women crying over how meaningful it felt to see a strong, fearless woman superhero finally placed front and center for once. What I’d forgotten was that the movie premiered less than a year into Donald Trump’s first presidency; almost exactly seven months since the 2016 election sent the country reeling with questions about what it would take to ever see a woman in the Oval Office. Maybe there was a reason we all needed a beacon of female power that summer.

When I was planning out what I wanted to cover in Women Of Action’s first few installments, I knew I should get to the topic of female superheroes sooner rather than later. And I also knew I was setting myself up for a bit of an impossible task. If there are two defining pop culture trends of the 2010s, they are the rise of superheroes as an absolute cultural juggernaut and the rise of modern feminist discourse about female representation. Gallons of digital ink have been spilled about the need for more female superheroes and why it took so long to get them—much of it by me. What more is there to say there hasn’t already been said?

So instead of looking at the film as a whole, I’d like to specifically zero in on four action scenes that represent the highs and lows of Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman tenure—starting not with her 2017 solo film but with Zack Snyder’s Batman V Superman: Dawn Of Justice the year before. Because even BvS haters have to admit that Wonder Woman’s official entrance into the DCEU absolutely rules. After wandering around the margins of the story as Diana Prince, Gadot disappears just long enough that you kind of forget she’s in the movie, only to emerge in her full-costumed glory, scored by one of the most instantly iconic superhero themes of the 21st century.

It’s a jolt of energy into a movie desperately in need of some. Watching Diana effortlessly slip into playful, gladiator-style action is a statement of purpose about how the DC films intended to use the character moving forward. (Twelve films in, Marvel’s big-screen female heroes were all still sexy spy and/or assassin supporting players.) And while the moment where Superman asks “Is she with you?” and Batman replies “I thought she was with you” initially plays like just some generic jokey banter, it’s actually key to understanding what makes the DCEU’s portrayal of Wonder Woman so singular.

There had been female-led superhero movies before, including 1984’s Supergirl, 2004’s Catwoman, and 2005’s Elektra. But those films were spinoffs of male-driven superhero stories; characters who exist specifically in relation to more famous male heroes. Wonder Woman is different. She’s not a love interest or a villain or a female relative who later stepped into a leading lady role, nor is she a member of a team like the X-Men and Fantastic Four franchises had given us. She’s been her own standalone heroine since she first debuted in All Star Comics #8 way back in 1941—right on through to her cover star appearance on Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine (headline: “Wonder Woman for president”) and the popular 1970s TV show that helped make her a household name.

She’s not “with” either Batman or Superman because she’s simply a hero in her own right; it’s pretty astounding to think that it took us until 2017 to get that concept on the big screen. For whatever else Batman V Superman does, it gets Wonder Woman’s entrance right, teeing up the promise of a different kind of female superhero story that Patty Jenkins’ solo Wonder Woman film would more than deliver on the next year.

Like the Barbie movie last year and Black Panther in 2018, Wonder Woman was a cultural phenomenon that brought out droves of people who might not otherwise think of catching an action blockbuster—breaking box office records and drawing higher percentages of female filmgoers than most superhero movies. Those craving a new kind of superhero representation were rewarded early on with an extended action sequence where Diana’s Amazonian sisters spring into action as a group of German soldiers storm their hidden shores.