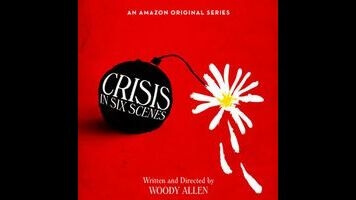

Woody Allen had a hard time with Crisis In Six Scenes—now you can, too

The week’s two biggest television premieres arrive with plenty of baggage. Sunday marks the delayed opening of HBO’s Westworld, a sign that you can’t stop progress, no matter how many objections you have to a legal waiver involving genital-to-genital contact. Two days prior, Amazon will introduce Crisis In Six Scenes, the Woody Allen miniseries whose announcement inconveniently coincided with resurfacing allegations that the filmmaker had sexually abused adopted daughter Dylan Farrow as a child. On top of that controversy, Allen copped to struggling with the process of making Crisis In Six Scenes. “I have regretted every second since I said okay,” he said in a 2015 interview with Deadline, following up to assure people that, for once, he wasn’t being self-deprecating for comedic purposes.

In at least one of these cases, the results are more James Cameron’s Titanic than White Star Line’s Titanic: There are no regrets involved in buying a ticket to Westworld. As for Crisis In Six Scenes, it’s not a total disaster, but it does embody a crisis all its own. In press materials for the series, Allen stresses that Crisis In Six Scenes is a “light comedy,” and it meets those modest ambitions. For better and worse, the Vietnam-era story of a suburban household upended by the arrival of a radical activist calls to mind various entries in the Woody Allen back catalog, from Take The Money And Run to Don’t Drink The Water to Small Time Crooks. But what the series fails to do, especially in its logy middle passages, is argue why this was the right story for Allen to tell in this particular format. Some skillfully deployed, binge-enabling cliff-hangers notwithstanding, there’s not much here to differentiate Crisis In Six Scenes from any other late-period Allen trifle, slurped down in under 90 minutes and forgotten until the next round of cryptic casting announcements.

Allen plays Sidney J. Munsinger, an aspiring novelist whose most significant cultural contributions are the advertising campaigns for a series of increasingly ludicrous-sounding consumer goods. (Recollections of Sid’s ads are the series’ most reliable gag; they’re sorely missed in later episodes.) The J.D. Salinger wannabe who pretentiously refers to himself as “S.J.” shares a well-appointed Connecticut home with his psychologist wife, Kay (Elaine May), and Alan (John Magaro), the college-age son of a close friend. This status quo is disrupted by wanted fugitive Lennie Dale (Miley Cyrus), a bomb-making enemy of the status quo who’s Patty Hearst without the brainwashing. The squares-versus-longhairs culture clash is positioned as the comedic ballast of Crisis In Six Scenes, but more than half the series is over before things start to go “boom.” Otherwise, the conflicts are as hackneyed as something out of the sitcom idea Sid keeps in his back pocket.